Australia's new clouds

Aussie quicks bowling the wobbleball, WTC points and Kookaburra's reinforced seam have made it incredibly tough to bat Down Under.

Buy The Art of Batting here:

Jimmy Clouderson was what the haters called James Anderson.

They said he couldn’t be effective outside England’s grey and unpleasant skies. But that was never quite true. The real difference wasn’t what was above his head, but in his hand or what he was standing on. The Dukes ball and grassier wickets are what made Anderson impossible to play.

And in England, he had both of them.

In Australia, he had neither.

England have been sending bowlers like Anderson to Australia for generations, who are incredibly suited to local conditions, but on the harder, flatter wickets, they struggle. What makes this even tougher for the English is that the Australian quicks do handle the UK wickets much better. So England make seam-friendly bowlers who get to Australia, get nothing out of the pitch, and local batters feast on the buffet.

The few times England have won in Australia, it is often with taller, faster or hit-the-deck quicks. Over the last few years, they’ve decided to pick these kinds of bowlers over their traditional fare.

That was part of the reason they moved on from James Anderson. He was just not the kind of bowler they needed anymore. So despite the fact he was defying the normal age curve like some cricket Paul Rudd and had won an Ashes before, England’s greatest wicket-taker was out of the team forever.

It made sense - if the Ashes are the only thing that matters - and he was not going to be used, so why not move him on? You might make arguments about dumping a legend, but the logic made sense.

Jimmy Anderson did not suit Australian wickets, and he was never going to change.

He didn’t; Australian pitches did.

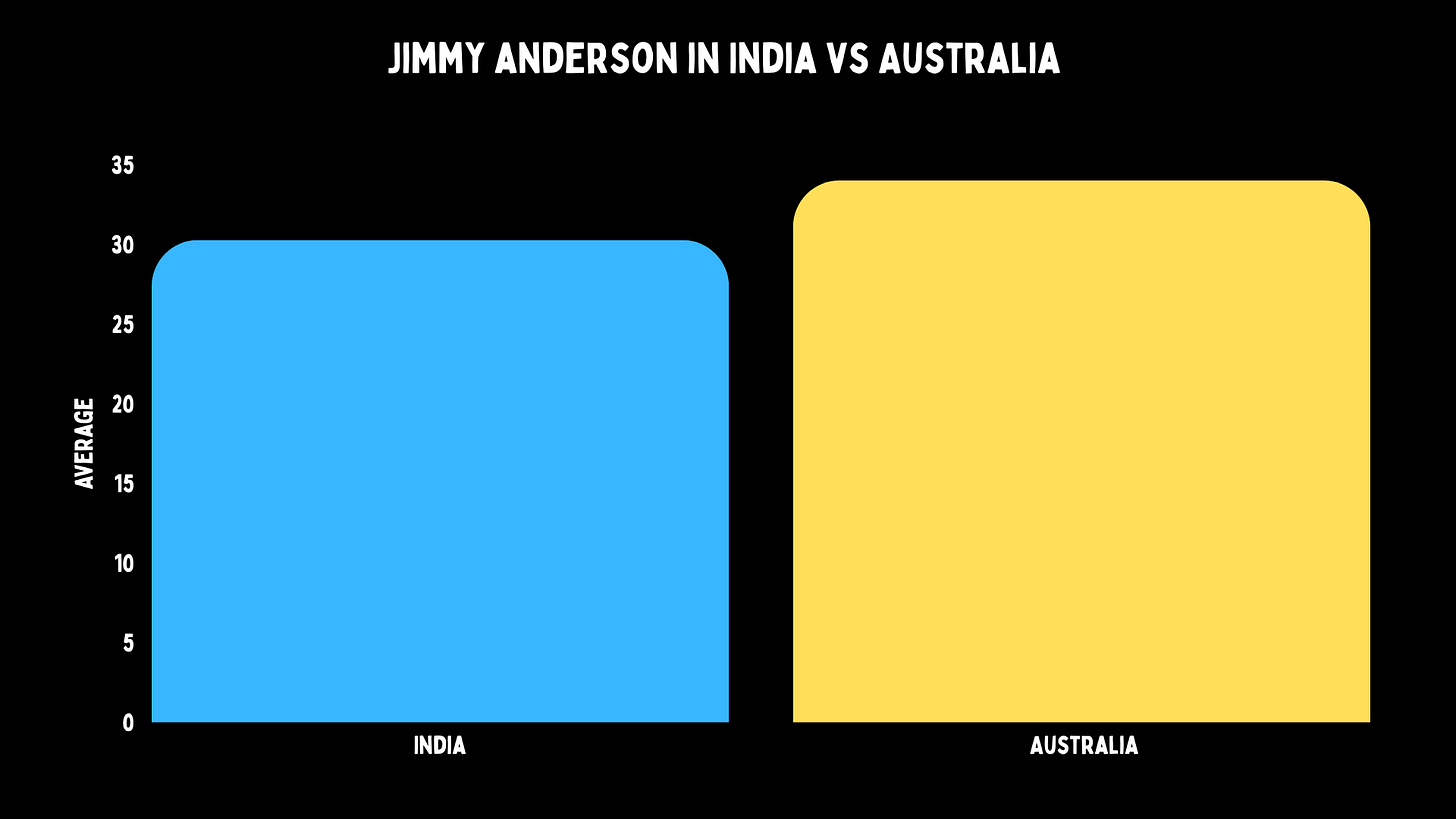

Jimmy Anderson averaged 34 in Australia and 30 on Indian pitches, which is the opposite of what you’d think. Anderson started as a quick bowler, and that should do well in Australia. But he ended as a surgeon who could make the ball reverse, and he found a way in India.

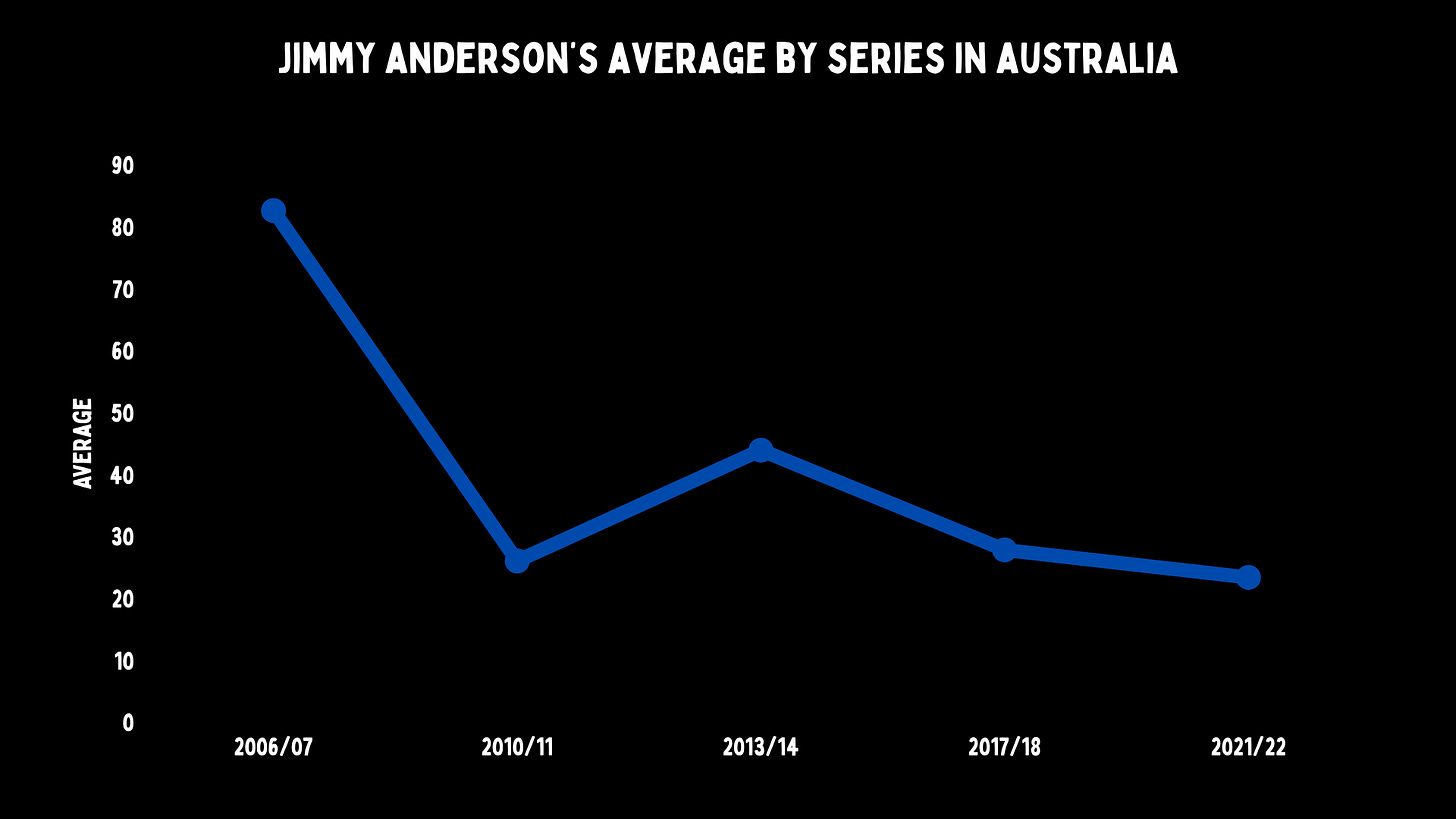

But Australia was a much more confusing place for him. His first tour was horrendous, taking wickets every 112 balls. In all, he went to Australia five times; three times he averaged under 30, and twice it was over 40. That is a weird pattern. Because he was either really good, or utterly horrendous.

His best series in terms of average was not 2010/11, when he and England dominated. It was the last time, where Anderson took his wickets at 23.5.

Now, I want you to sit and chew on that for a moment. The best series Anderson ever had in terms of average was the one which convinced England to never take him back again.

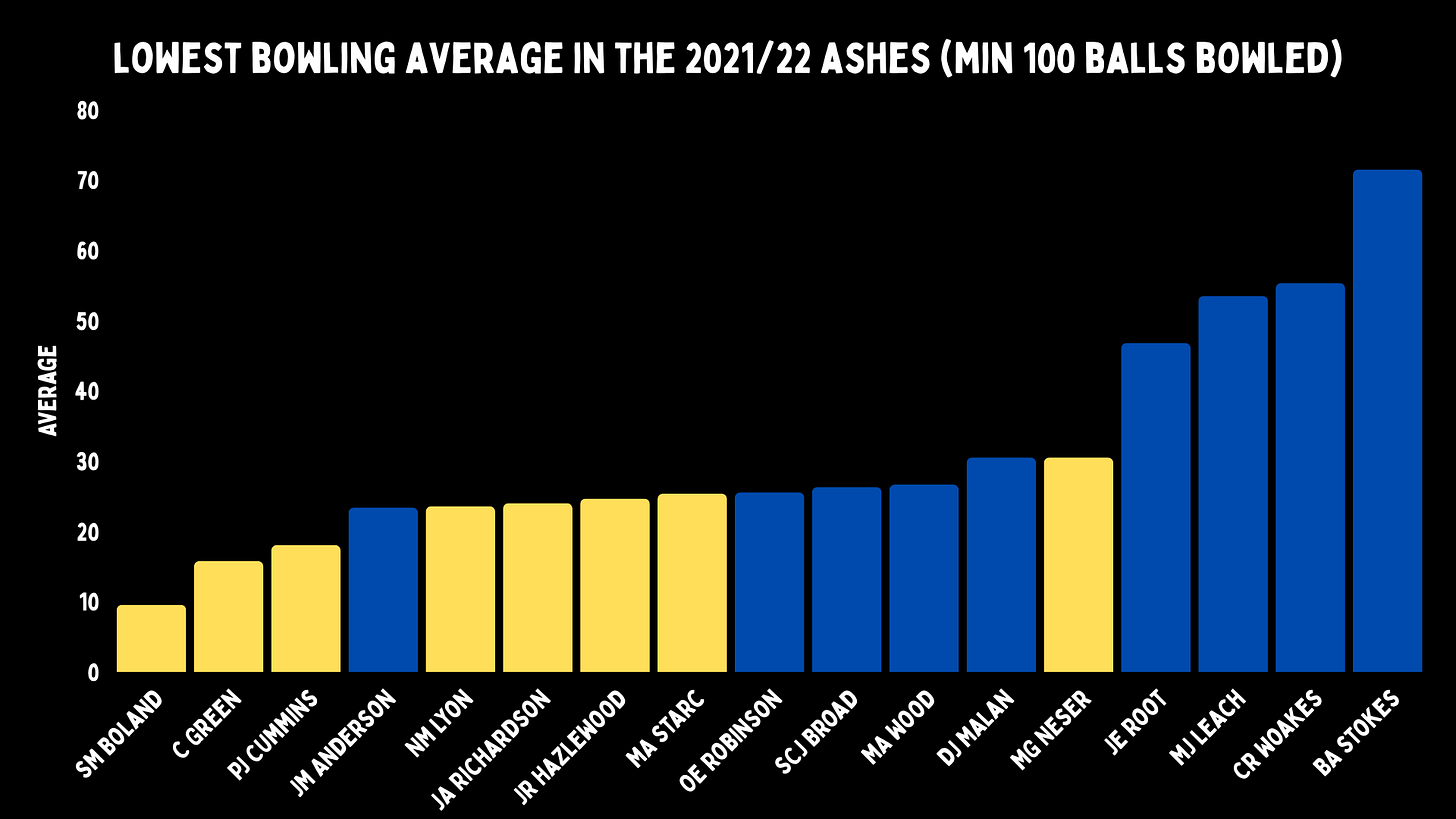

Those numbers need context. Australia had two bowlers with an average in the teens, and Scott Boland took 18 at 9.5. Anderson had the fourth-best record, but was only 2.6 runs better per wicket than all bowlers in that series. He almost became a great finger-spinner, with an economy of 1.79 and a strike rate of 78 balls per wicket.

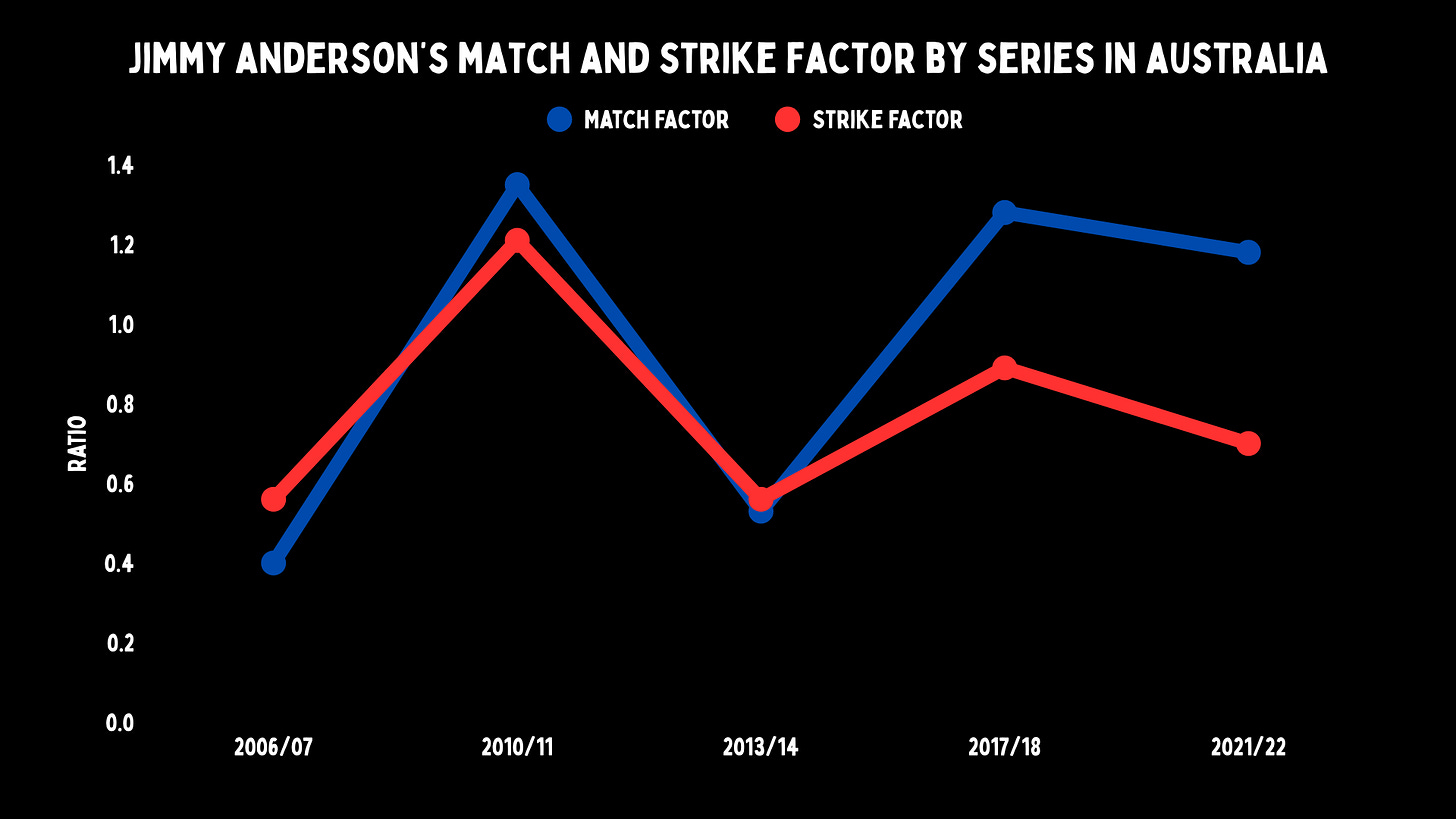

On the advanced numbers, you see that Anderson’s last two tours - even as England have been shivved to death in a manky alleyway - have held up well on match factor. It’s just that it takes him a million years to take a wicket, and by then, Australia have won.

In a traditional English attack on a normal Australian pitch, there would be no point taking Anderson back.

But when you have Jofra Archer, Mark Wood, Brydon Carse, Josh Tongue and Gus Atkinson, perhaps the thing you need is the English-style seamer.

Which might seem weird if you’re a casual fan, because generally you need bowlers who hit the pitch, but also now, more than ever before, you need people who can seam the ball. And while Anderson started as a swing bowler, he ended as a (wobble) seamer.

But it wasn’t the change that Anderson made that affected everything; it was Australia’s evolution.

When the wobbleball first took over, Australian bowlers told me it would never work there. Anderson proved in 17/18 it would, even if that didn’t help England at all. But the Australian bowlers were still suspicious.

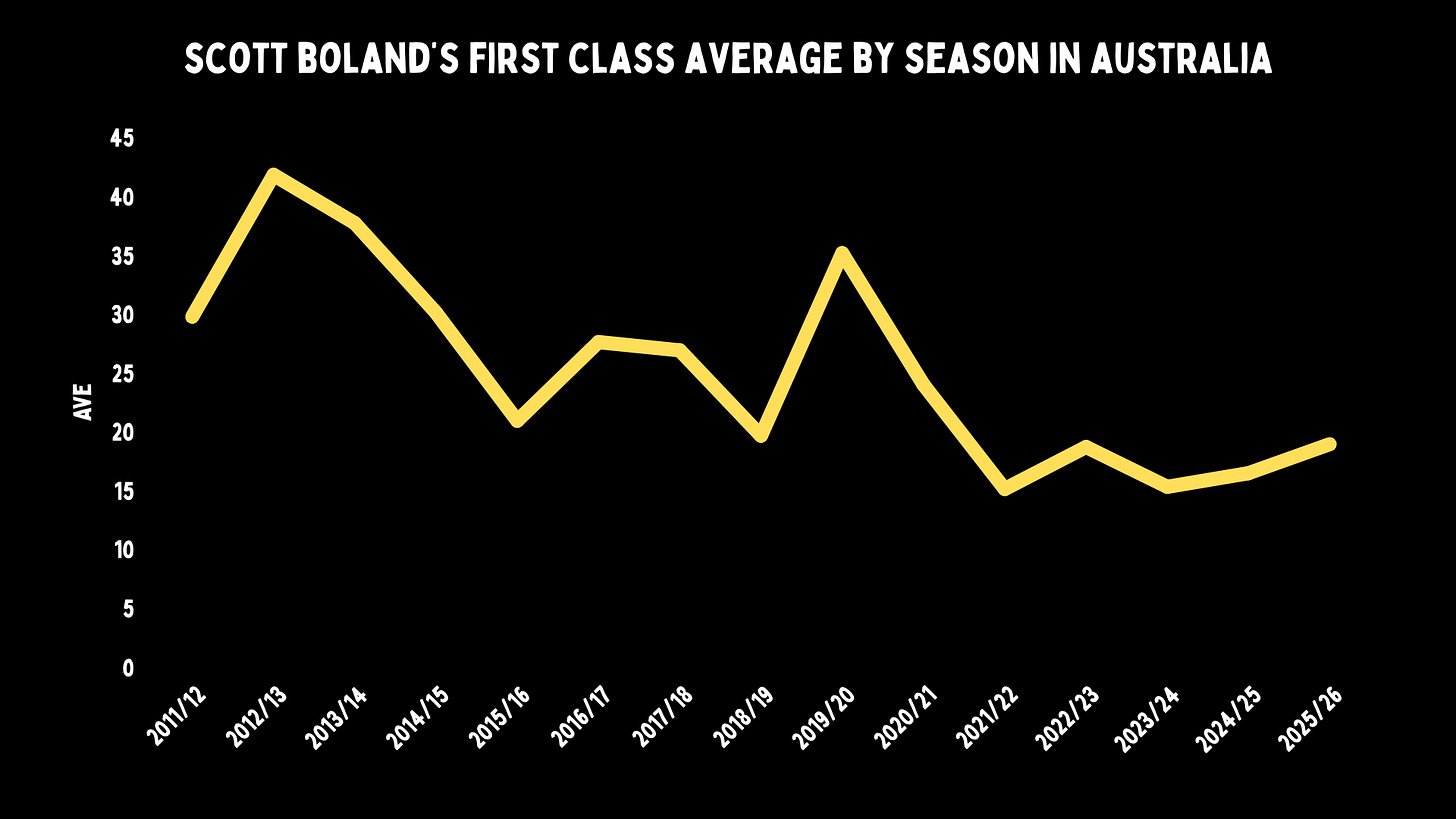

They shouldn’t have been. There were two case studies that proved to them this delivery could work down under. Peter Siddle brought the wobbleball back from a stint at Essex, Scott Boland started bowling it shortly after, and you can tell exactly where by looking at the averages.

Stuart Clark was a wobbleball bowler well ahead of his time. I have a very flimsy theory that he played against Mohammad Asif early in his career, and managed to copy the delivery. Again, look at his average: he clearly becomes a different bowler at one point.

But still, Australians were suspicious of the wobbleball, probably because although Asif was a Pakistani, most of the evangelising came from England. And Australian cricket is taught to believe that nothing good can ever come from English cricket (please see, Ball, Baz).

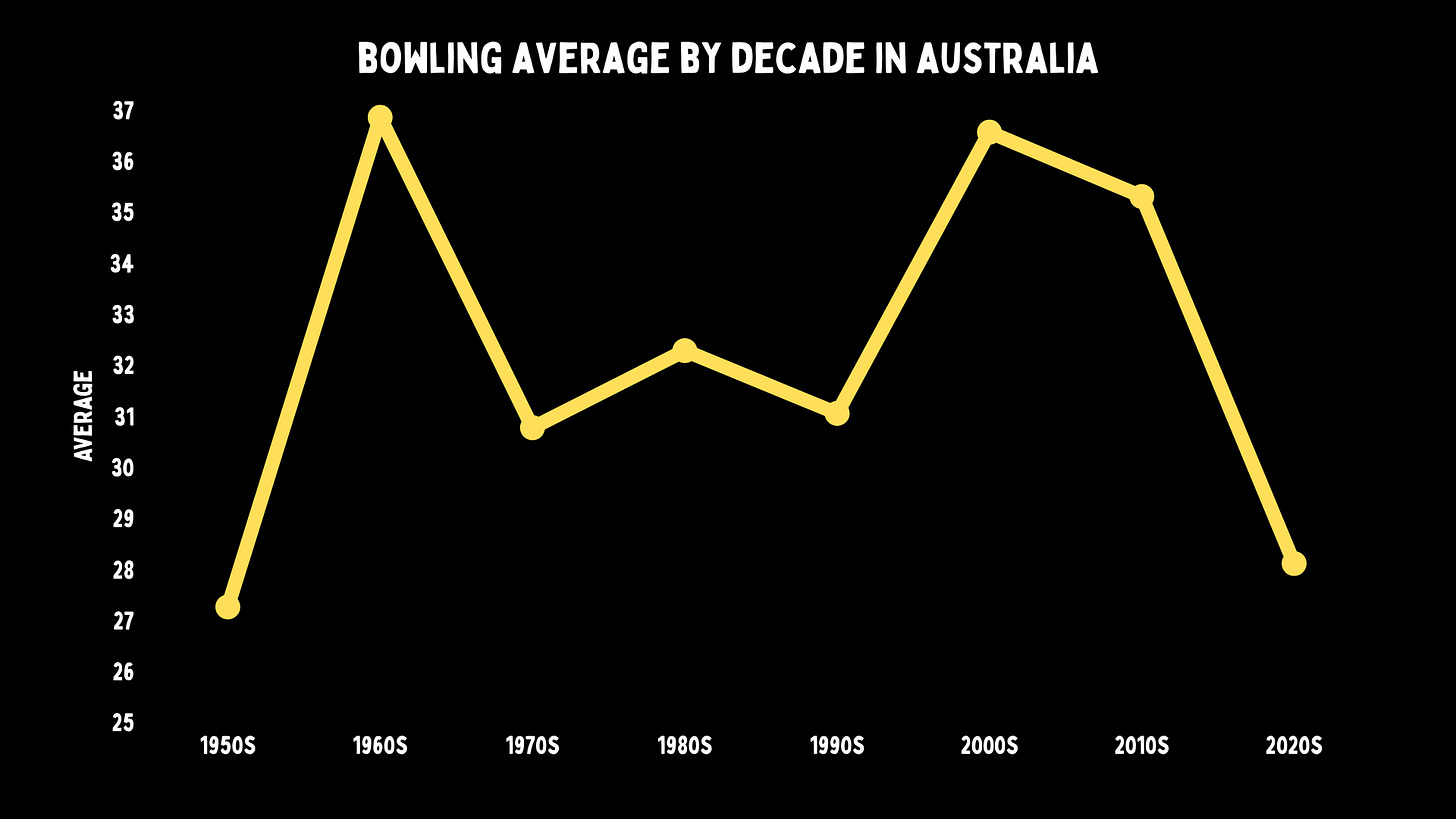

Australian wickets have always been great for batting. The opposition struggle, but never the Aussies. That has stopped now, and this is the lowest scoring period on Australian decks since the deadball era of the 1950s.

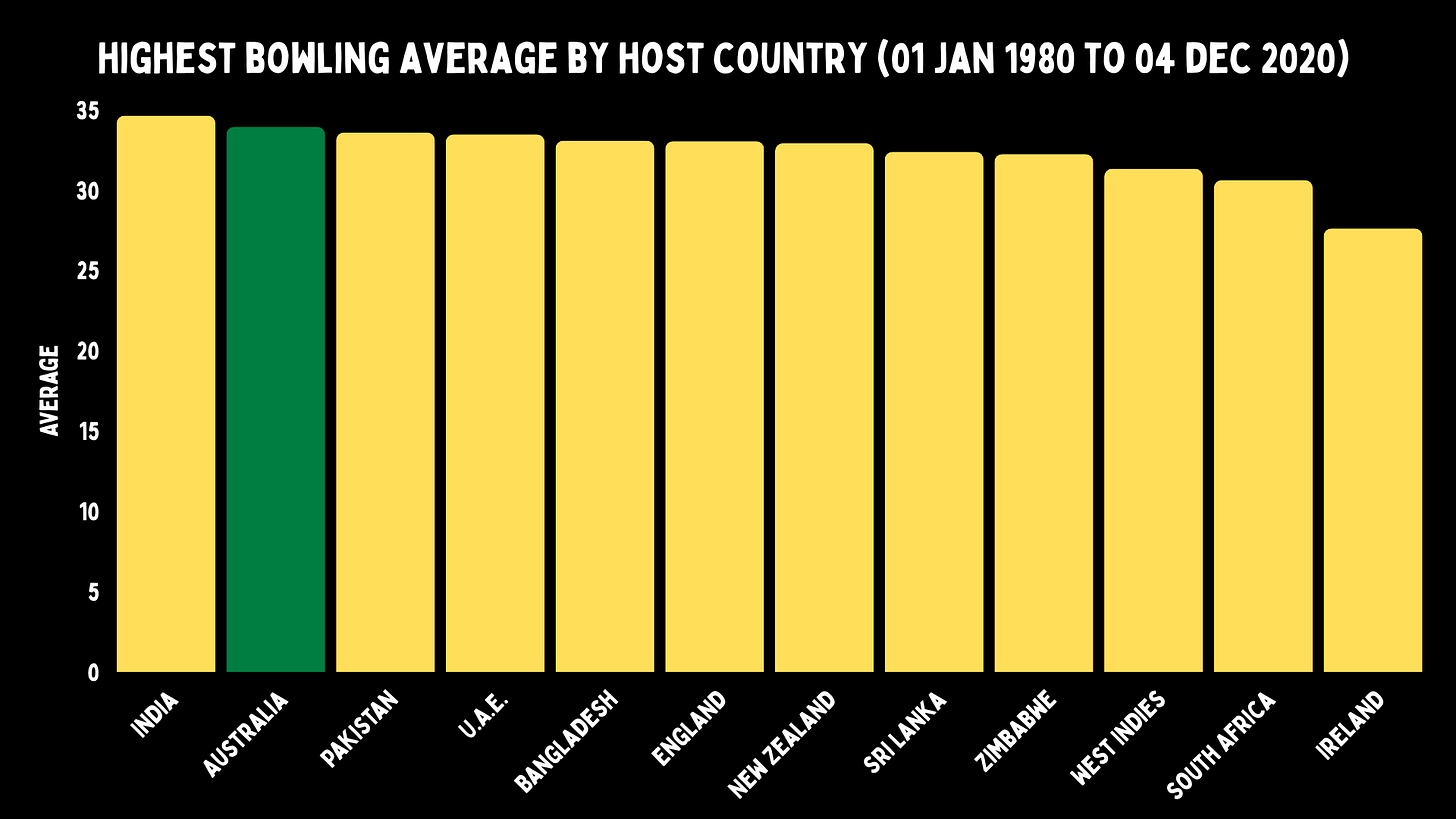

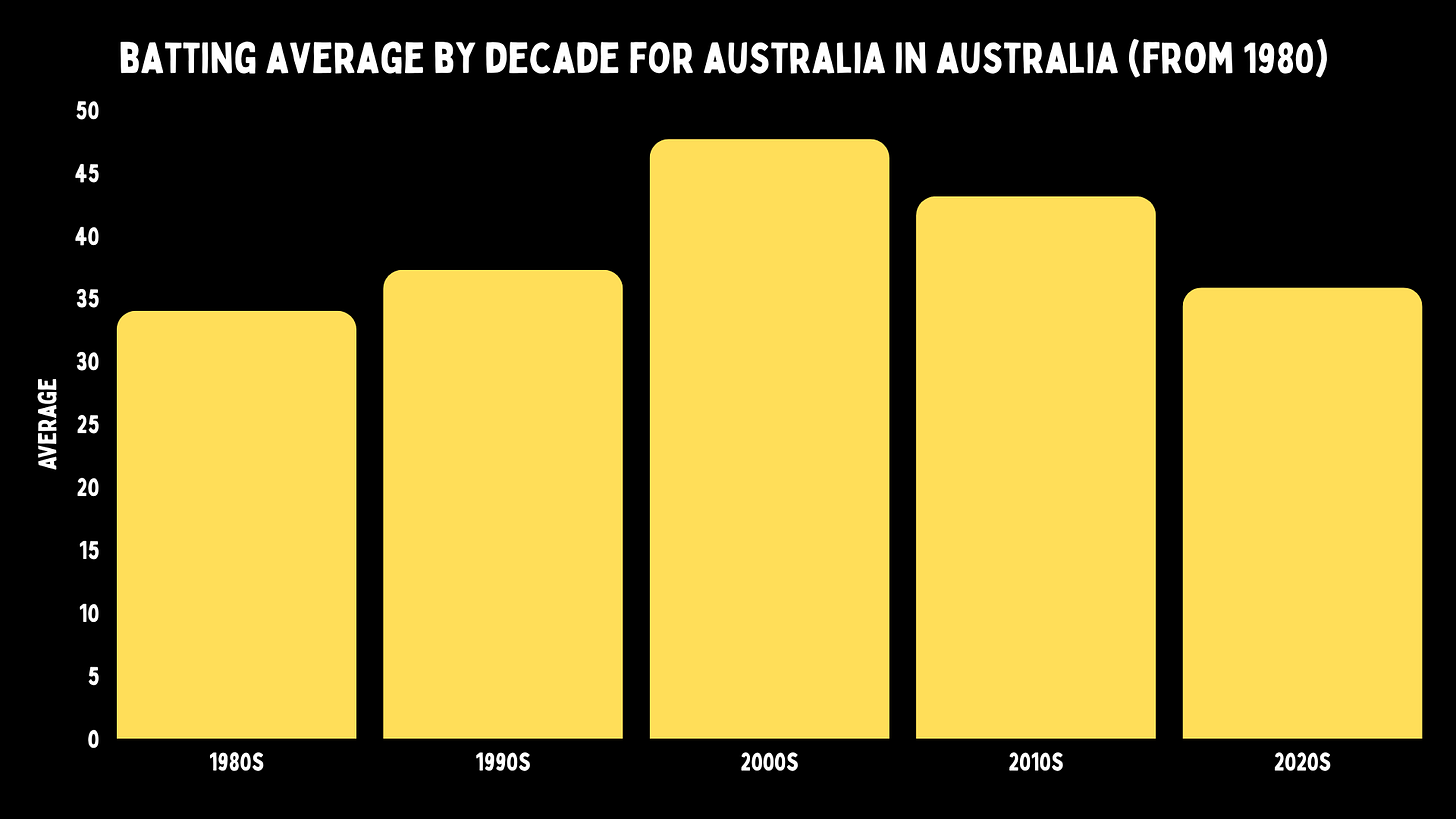

Since 1980 - the unofficial beginning of covered pitches - Australia has almost always had the highest average per wicket. They are just under India in that time. Those are historically high scoring rates.

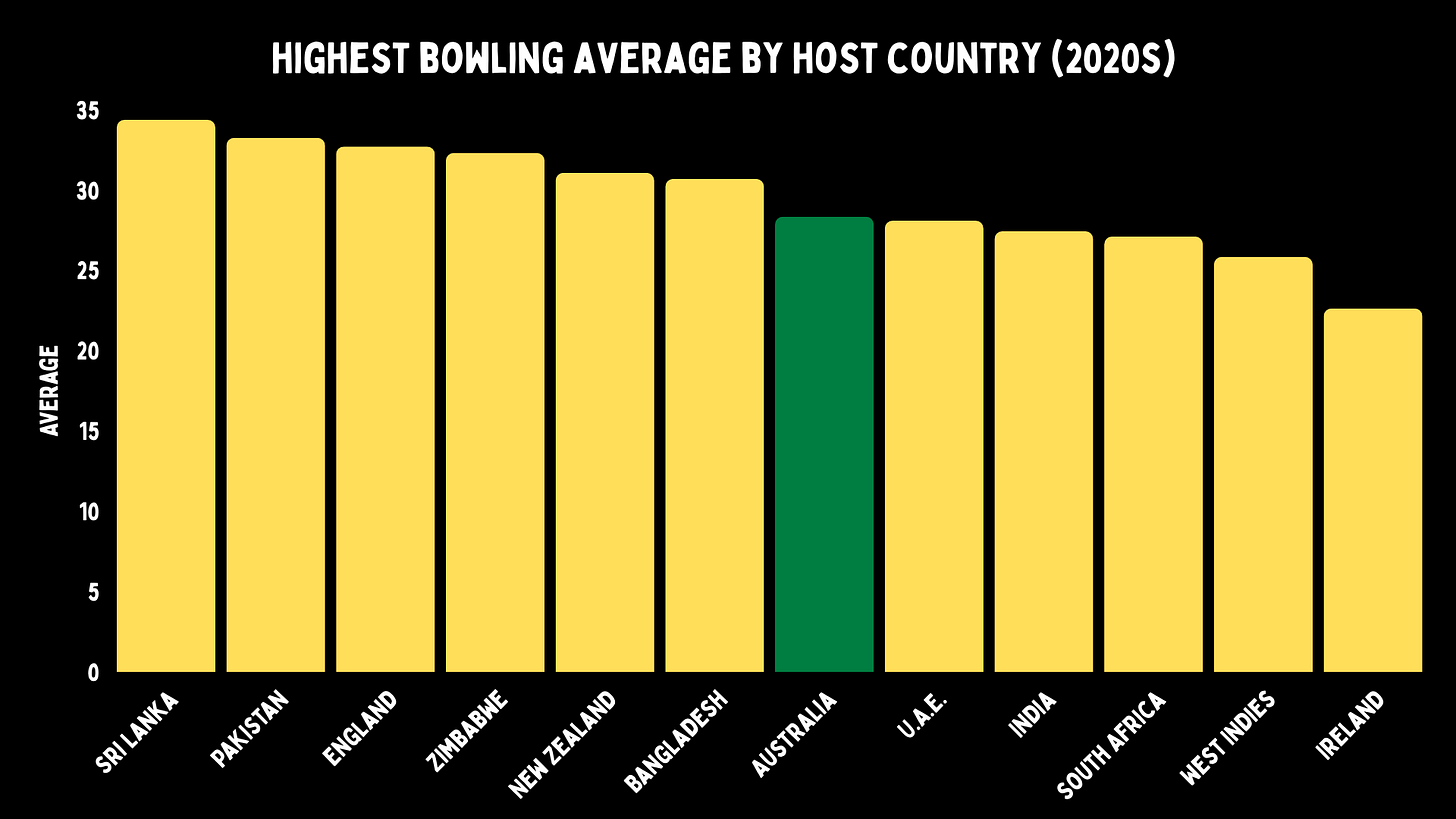

Australia, India and Pakistan are all roughly at 34 runs per dismissal. Since 2020, Pakistan has kept theirs high (for now at least) but India has been averaging 27, and Australia 28. This isn’t because they stopped finding batting talent; it is often the same players as before, often in their peaks, finding it impossible to score anymore.

That is a huge drop. It is currently easier to score runs in Bangladesh than in Australia.

The last time Aussie batters were this bad was in the 1980s, their worst ever period. This is on paper a great group; Smith, Labuschagne, Head, Khawaja and Warner have played in this era. They should be making runs at home; instead the drop is 7 runs from the previous decade.

There are a few reasons for this. One is about World Test Championship points. Many teams have begun to prepare their pitches more for bowling, primarily to secure points in home games. Another is that Australia have an ageing group of fast bowlers. Their backup seamer is Boland, and he is 36. So you don’t want to have your three most important players bowled into the ground (as happened against India a few years back). There is little doubt we see more Australian surfaces with grass coverage and lateral movement than ever before, not just in Tests, but no one is making runs in Shield cricket either.

But the real change was something that Cricket Australia had little to do with. They (like most international teams) get their Test ball from Kookaburra, a small Melbourne company that also makes hockey equipment. Their balls were always compared to Dukes, who were far superior, and they even lost their contract with West Indies for Tests. So they decided to change their ball to ensure it didn’t go soft so quickly, and also to make it produce more exciting cricket, like the Dukes. They did this by reinforcing the seam with plastic.

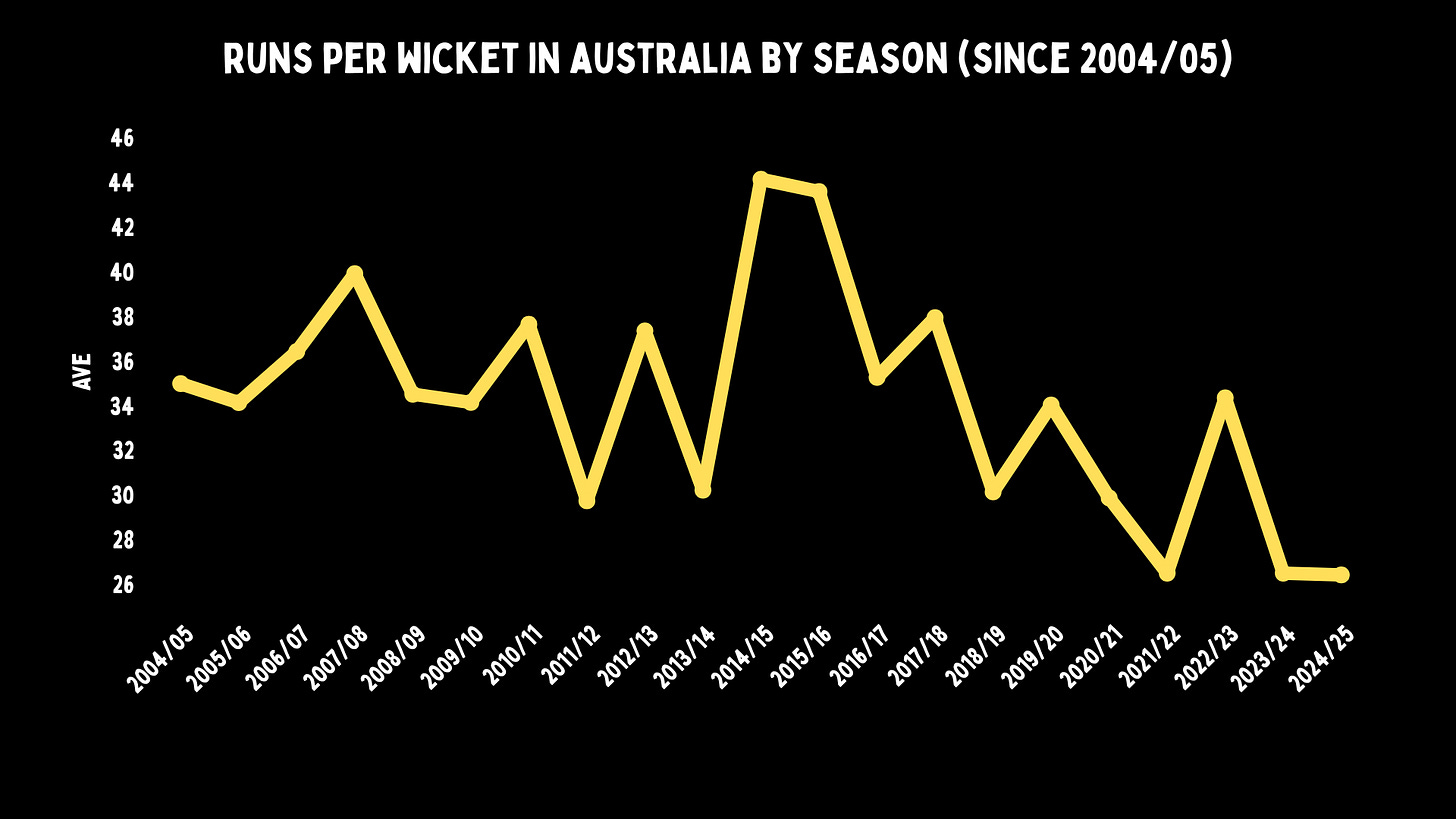

According to our sources, the first ball used that had this change was when India was bowled out for 36 in December of 2020. Whether all the balls were changed for that series is not known. And you can see averages were already on the way down before then, but there have now been three seasons where the average is around 26, and before the change, the average barely even got near 30.

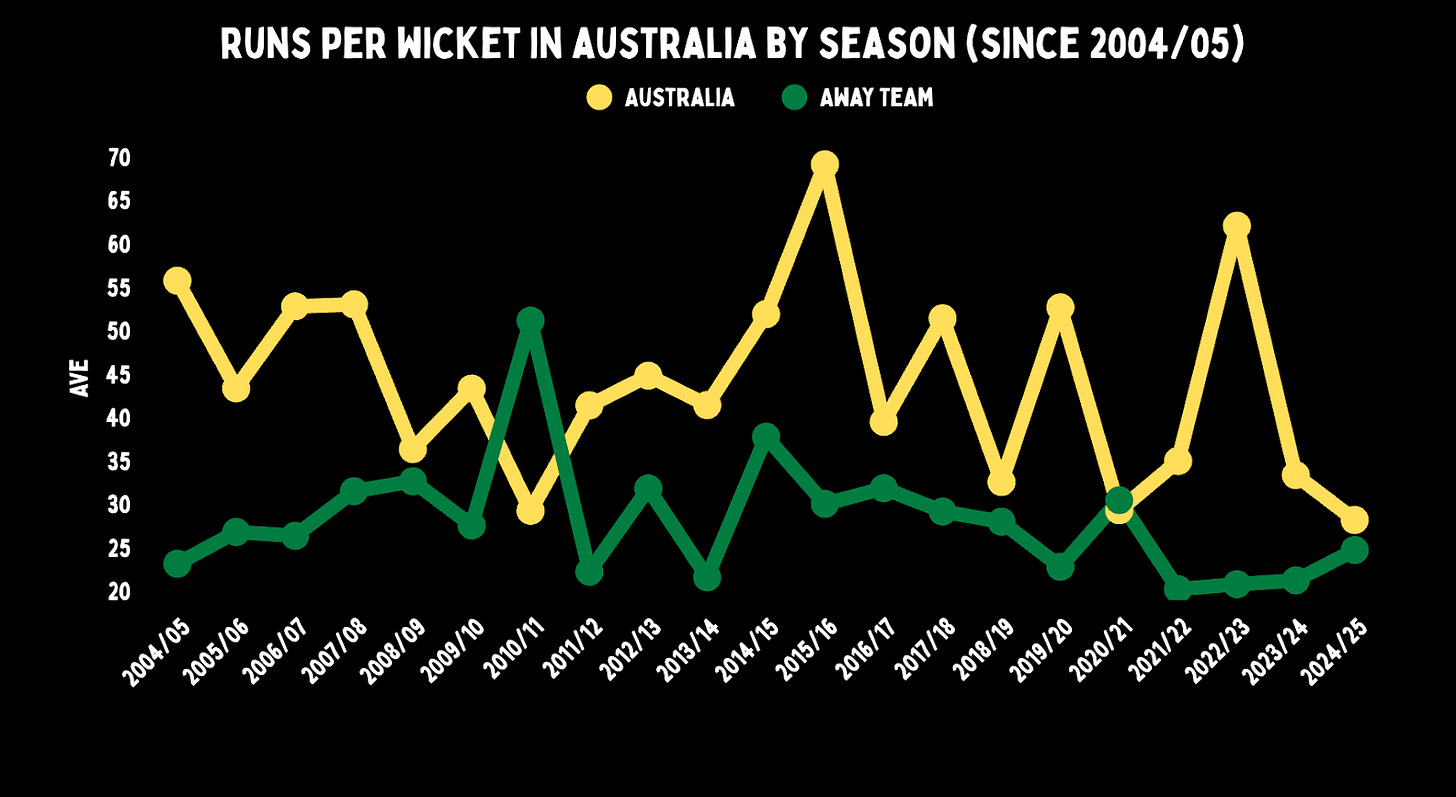

Touring teams often struggle in Australia, but the home side almost never does. From 04/05 until the summer of that Kookaburra refurb, Australian batters had only twice failed to average more than 35. Since that summer, they have failed to go above 35 four out of five times. Last season, they beat India at home, even though their batters averaged only 28 per innings.

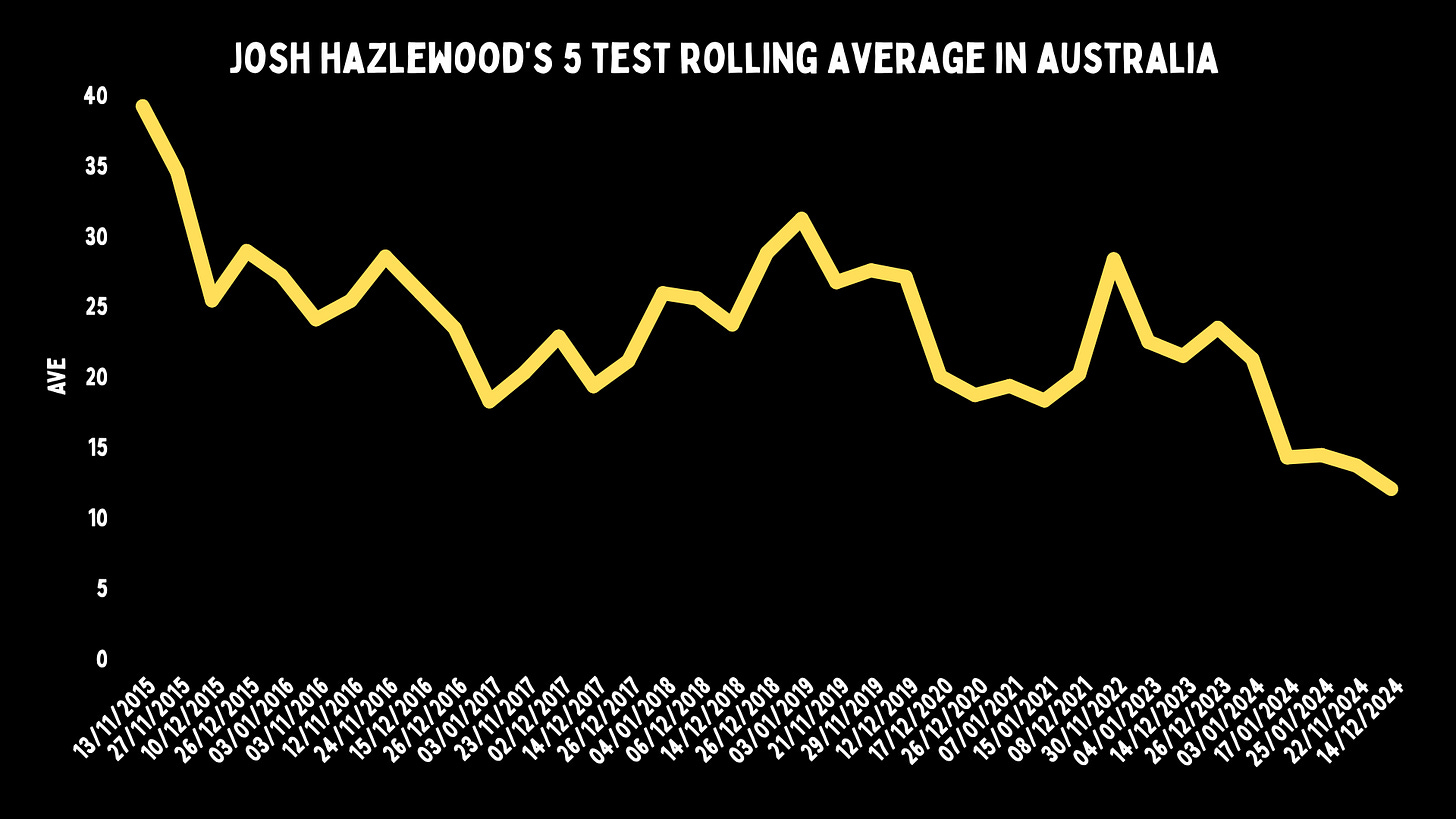

The weird thing is that Australian wickets have become more English than those in the UK at times. Josh Hazlewood has always been a hybrid Australian/English style seamer, much like Glenn McGrath before him. And he used to be a very good bowler at home, now he’s unplayable.

Anderson isn’t Hazlewood; he’s shorter and skiddier. And you could certainly argue that he shouldn’t play in every Test.

Anderson - even if in the squad - wouldn’t have played at the Perth Stadium. But the spell that won the game was from Scott Boland, at an Anderson-like pace, getting the ball to seam an Anderson-like amount off the surface, while delivering with Anderson-like accuracy.

Australia has artificially made itself cloudier; they’ve got a budget Dukes ball as well, and the bowler from England most likely to do damage is Jimmy Anderson. Who, instead of being used in two or three Tests when needed, is podcasting and working out in the Old Trafford indoor nets. Jimmy still has clouds above his head, but not the right ones.

You might need to ask your analyst to rerun the Boland/Clark first-class bowling average charts - they're currently duplicates of each other (just with differently labeled/scaled X-axes)

He took 5 wickets at 80+ in his 4 Tests in the last home Ashes series. It's true that Boland also struggled that series, but it did feel as if the end was nigh for Jimmy.