Basil D'Oliveira: The selection that changed the world

A forensic look at the biggest selection in cricket.

In early 1968, a lot was going on in the world. Vietnamese war, the Olympics Black Power salute, Martin Luther King's assassination, humans walking on the moon, and the USSR invading the Czech Republic. Yet at the time, the leader of a country that was in geo-political turmoil and had trade sanctions was getting daily updates on how Derbyshire’s bowlers had gone up against Worcestershire’s star batter.

The South African government and their prime minister BJ Vorster wanted to know if England would select Basil D’Oliveira for their 1968/69 to tour their nation.

And all these years later, I want to know the same thing. Should the MCC have picked Basil D’Oliveira to tour South Africa? Not because of politics, but purely on cricket.

Because this is the cricket selection that changed the world.

Cricket scorecards aren’t like other sports. They don’t give you the result, they give you the story. Other sports have 1-0, 112-111, 6-4, 6-3, 5-7, 6-4. They tell you how close the game was, and the result, but not much more. They are tweets, cricket’s scorecards are novels.

You can find out who killed the butler in the billiards room with the candlestick if you know how to read them. Cricket scorecards unfurl in front of you, and while they can’t tell you everything, they give you something.

The entire summer of ‘68 in England doesn’t make sense. The scorecards say one thing, the reports another. That’s not unheard of, sometimes the scorecard is wrong, and sometimes the journalists are.

In the case of Basil D’Oliveira, something has never quite added up. It is possible no one ever knew the full story, almost all of the people involved have passed on. There were so many different people who it seems never wanted the full story, or at least their part of it, to come out. Even Peter Oborne’s book, which will get as close as most, can only tell us so much. But what we know is this, what happened doesn’t make sense when you look at the scorecard.

It wasn’t the only confusing number about D’Oliveira, his career was somewhat on the back of lying about his age. He was born in either 1935, 33, 31 or even 27. D'Oliveira knew that if he ever gave his correct age, his chances of getting much more than a league contract would have been far harder. So he just lied.

We don’t know any real numbers on his age, but there is plenty of other data on his cricket to scour. D'Oliveira might be the most interesting cricket selection decision in the history of our game. Because despite the race and politics that were involved in his selection, there is cricket behind what happened.

First, a history lesson.

Basil D'Oliveira was born in South Africa, but because he was not white, he could not play for his country. Not only that, because of the colour of his skin, he couldn’t play against the best players. This meant that no one knew how good he was, and also it was incredible that he got to this level inside a purposefully poorer cricket system.

By writing letters to known people in England, he eventually found his way into league cricket. Despite being great in it, the attacking way he played led some to disregard him as a weekend slogger. It meant that for the second time, he was overlooked. It took him four years to get a first-class career. This was the only time in his career he was tested for real, he had been playing club cricket until this, and he starred straight away. Soon he was playing for England.

Everything I have just said would make this one of the most amazing stories in sport, but what happened next actually makes it bigger.

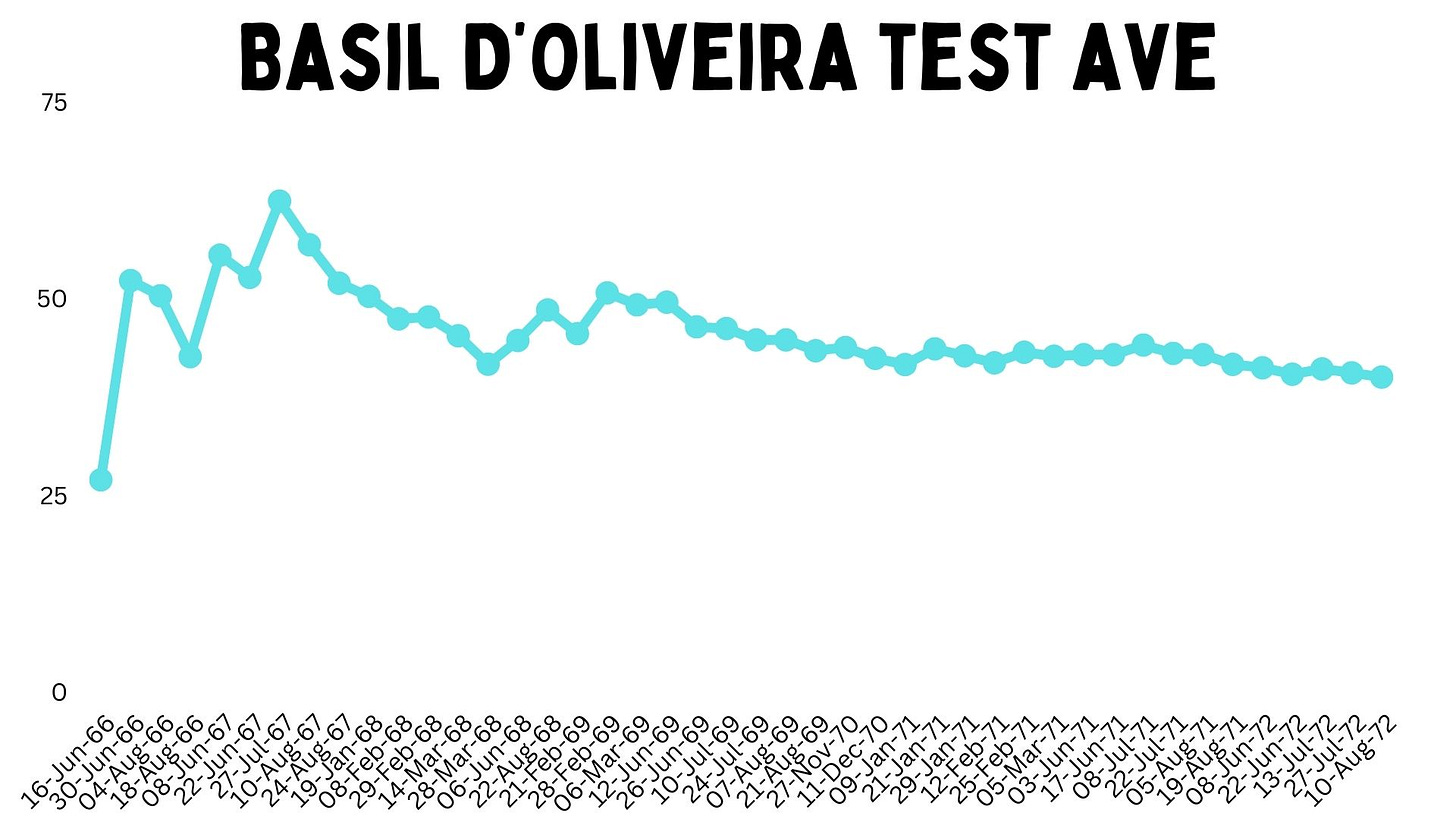

But first, we need to look at what he did in Test cricket, because all that plays a part. D’Oliveira played 44 Tests between 1966 and 1972. (He actually played the most in that time.)

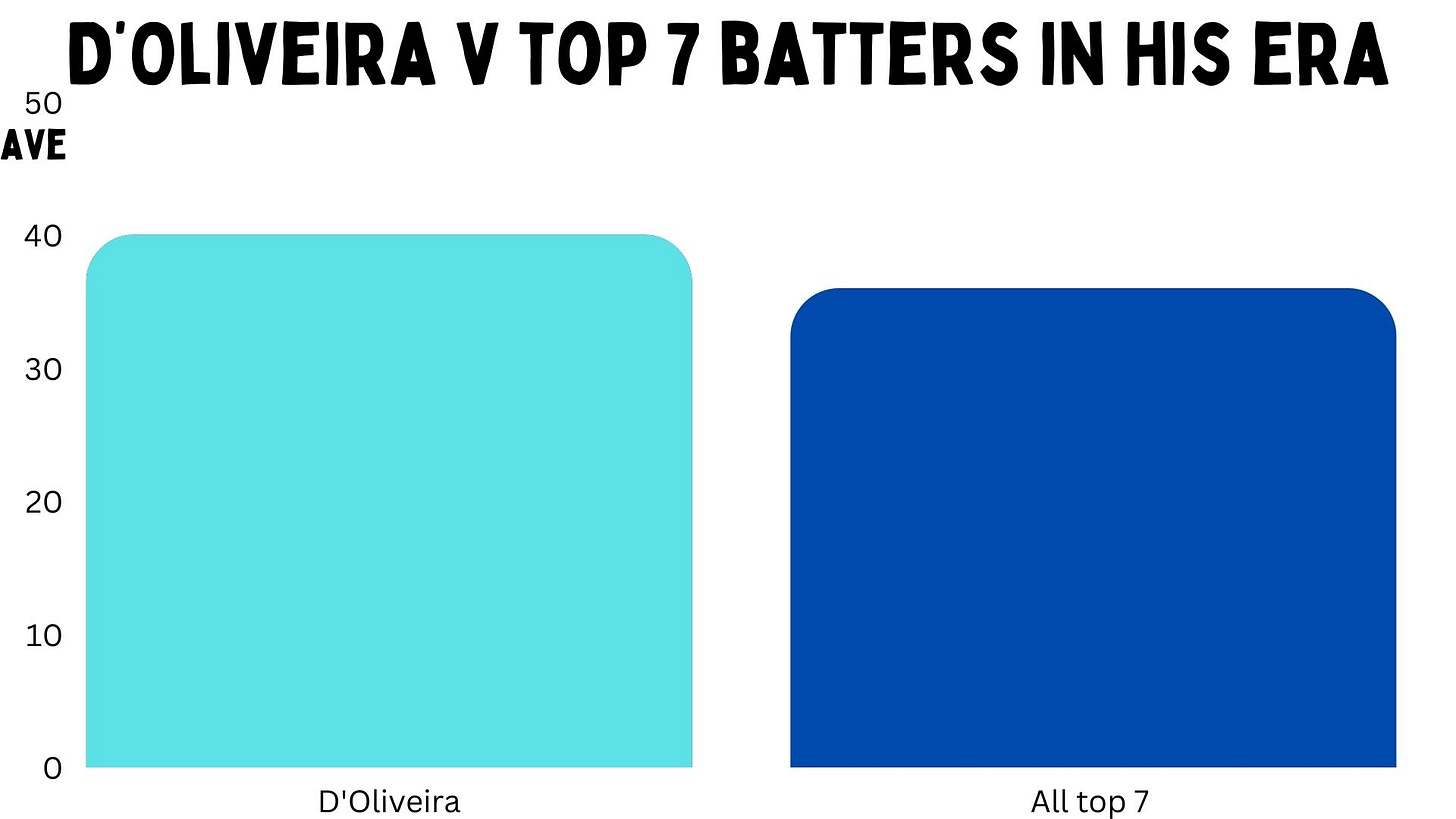

He ended up with a batting average of 40, the average top seven player in his era was 36, so he was around 10% better, but nothing that special. But he was a lower-order player.

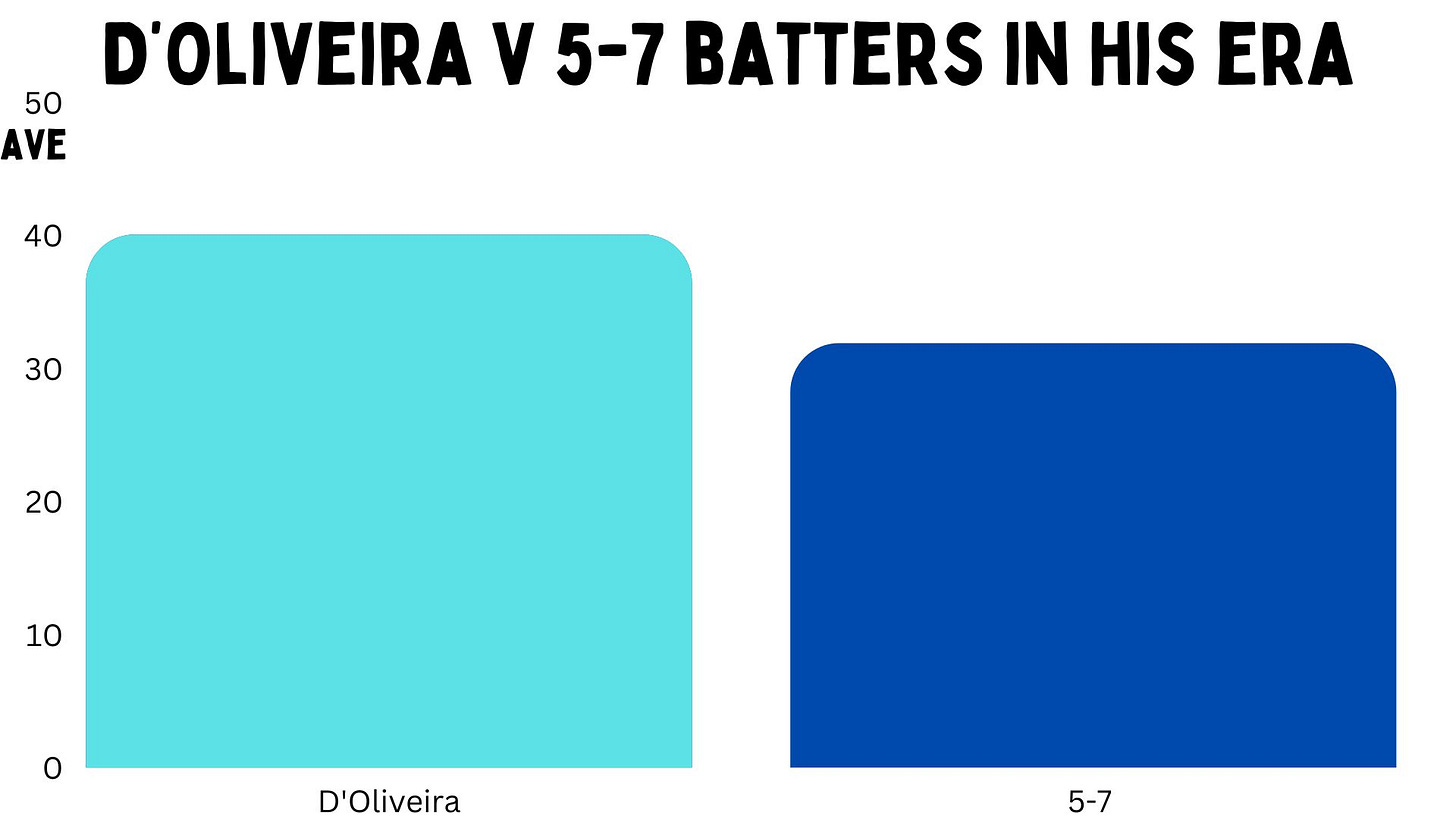

Mostly he batted between five and seven. And if you compare him to players in similar roles, he suddenly looks a lot better.

I think he was a plus batter, but there are two things worth noting. He did get old. How many years were on the clock, we don’t know. But towards the end of his career his decline was a little steeper.

His last 10 Tests really were quite poor. But he was kept around not just because of his batting.

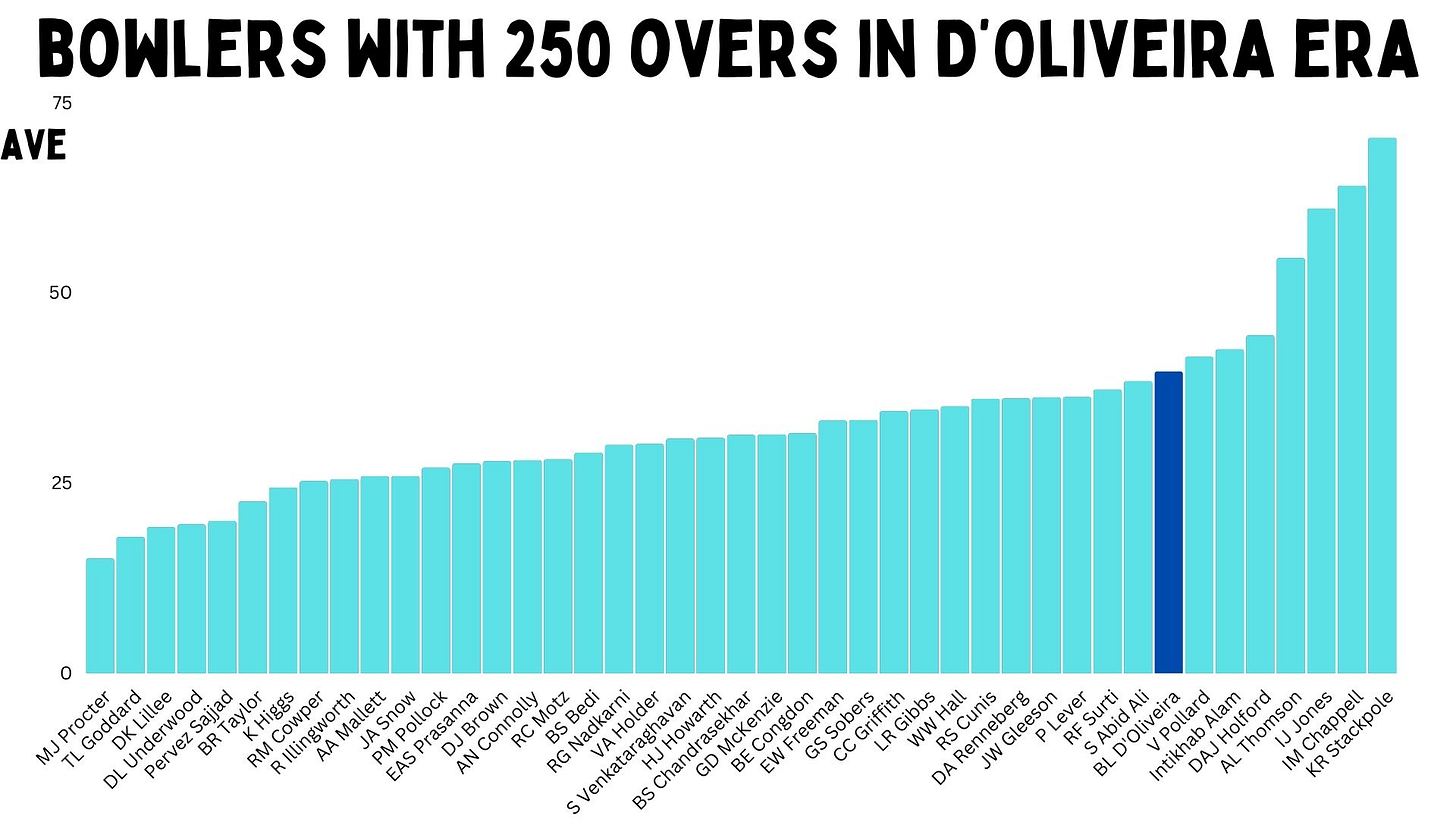

Basil D’Oliveira could bowl. It was not sexy, it was not even playful. It was dour medium pace and he averaged nearly forty doing it. But he still took wickets at a rate of just over one a game, and he did that right throughout his career.

That was not the only reason they bowled him through. No one could hit him off the square. If you’re a fifth bowling option, you are not going to be good at taking wickets and being economical, but even good at one is enough. And D’Oliveira was frugal as hell.

Think of him like a Colin de Grandhomme-type bowler, or maybe late-career Shane Watson is the best modern-day comp. To go at less than two an over as a part-timer is quite the feat. No matter how you look at it, this guy who was as young as 31 when he made his debut, and as old as 39, was clearly an above average Test player.

But in 1968 there was a lot going on. The Ashes were being played in England, and at the end of that summer England were going to tour South Africa.

If he went, England were going to take back a non-white South African player to a place that had done everything in its power to tell their people that people like him were not special.

How do you make that claim while a 30-year-old who never played first-class until his late 20s is coming back to play with the mother country?

There are other things going on as well. D’Oliveira started his career incredibly well, 27. 76. 54. 88. 7. 4. 109. 24*. 33. 59. 81*. After ten Tests D'Oliveira was averaging 50. But in 1968, he entered a slump.

England toured the West Indies in 1967-68. D'Oliveira was facing Charlie Griffith and Wes Hall were there, but it wasn't the express pace that worried him. He failed against all the bowlers. Only one fifty. D'Oliveira struggled with the pressure at this point, he took to drinking, and some in the West Indies called him a sell-out for playing in a white team. It is worth noting though while he failed in the Tests, he did great in the first-class games, averaging 40 for the tour. So his form hadn’t cratered completely.

The slump was not bad enough for him to miss the first Ashes Test. Australia made 357, D’Oliveira delivered 25 overs, 11 maidens, 38 runs and 1 wicket. Tight and few wickets, just the way he liked it. Though he was oddly used as one of the frontline bowlers.

England struggled in reply, making 165. D'Oliveira made a torturous nine. Australia added 220 more in their second knock. For some reason D’Oliveira only bowled five overs, taking 1/7. That one was important though, it was Bill Lawry, who averaged 47.

England needed 413, a nominal total, and D’Oliveira entered the innings at 105/5. England would more than double their total from there, making 253. 61 of those extra runs were by his teammates, he added 87 runs, not out. England lost, but D’Oliveira’s innings wasn't talked up. He made his runs when England were already going to lose the game was the narrative.

But, actually, he put on an 81-run partnership with Bob Barber when they were still a chance of taking the game deep. Alan Knott, one of the greatest keeper batters of all time was in next. Oh, and the wicket was considered unsatisfactory, so he made runs on an uncovered unsatisfactory fourth-innings wicket when no one else in his team could. But it wasn't a good innings.

So I went back to read the old Wisden reports.

Now, there is nothing in his Test record to that date that suggested he could ever bowl first change, that is obviously a mistake. But, his first innings certainly kept the pressure on Australia, as he bowled a maiden almost every other over. And in the second innings, he was bowling very well when taken off. It's weird that there was no mention of his short second innings spell. Regardless, how on earth is 2/45 that bad? For you non-maths nerds out there, that's an average of 22.5 per wicket, and even in a low-scoring game, the average wicket in this match fell at 24.87.

Now did Basil D'Oliveira look innocuous when he bowled? Undoubtedly. He did almost always, he was a slow county trundler. Everyone knew this, the writers and selectors, and yet suddenly this medium pacer was supposed to be a frontline bowler. It was baffling.

It was as if they were setting him up to fail. But, he didn’t. 87 not out and 2/45 is a good match, even if it had no impact on the game in total.

Oh, and this is my favourite thing, it’s so small, and usually I don’t care. But for this match, teams each had a batting and bowling player of the match. Guess who was England’s batting player of the match, D’Oliveira. Well played, random adjudicator.

I don’t think we can just obsess over the 87, he was clearly not batting like before. You have to weigh up everything.

Now this is the kind of thing that would have been done manually in the old days, and rarely. So maybe no one had these numbers, but if you included the West Indies tour, and this Ashes, plus all the tour games and first-class matches for Worcester, in 1968 D’Oliveira was averaging 40. Hardly the end of the world for a slump, especially if you are still bowling well.

So he had a poor series in the West Indies, was averaging 40 in first-class, had just made 87 and was misused as a frontline bowler but did okay. Based on all that, there is no way England should have dropped him.