Bob Simpson, the one-and-a-half cricketer

He was a professional before the term was in vogue, and changed cricket forever.

Buy your copy of 'The Art of Batting' here:

The ball is flying towards first slip; he’s standing wide. He loves to dive around more than most players do in that situation. He believes he can stretch out further than a normal slipper will. He extends every cordon by half a body. But here, the ball is coming straight to him. And that is what he wants.

He gets right behind it, and then he lets it hit the soft part of his chest. Slip fielders do not do this. If you saw it for the first time, you’d assume he’d made a huge mistake — that he got his hands wrong, and that it was about to go down. But when the ball hits the chest, the hands come around it to clutch it to him. He takes the catch.

Bob Simpson almost always took the catch. Whether he was too wide at slip and had to dive, or as Ian Chappell would say, while letting “the ball hit the soft part of his chest and then clutch it to his bosom.”

In 62 Tests, Simpson took 110 catches. Steve Smith is at 1.7, and that is incredible. Anything over 1.3 is brilliant. Simpson beats both those marks. He was a first slip to pace and spin, and among players with 50 Tests, no one has ever taken more catches per game than him without gloves on. He almost took one per innings. The man literally caught the ball like no one else, in more than one way.

Simpson had the softest hands and chest in the game. He embraced the entire sport and clutched it to his bosom.

***

Bob Simpson could bat, bowl and field. His legspin wasn’t always needed in an Australian team with Richie Benaud, but he was a Joe Root-level wristy. You didn’t want to sleep on his bowling. His ability to catch flies at slip, and also stand wider, meant that when Australia were in the field he was always in the game. He was like one and a half cricketers for them.

That suited his personality. It’s how he saw cricket. He wasn’t just there to bat and forget about the rest. He was coaching himself in almost every moment. Looking for one-percenters before the term even existed.

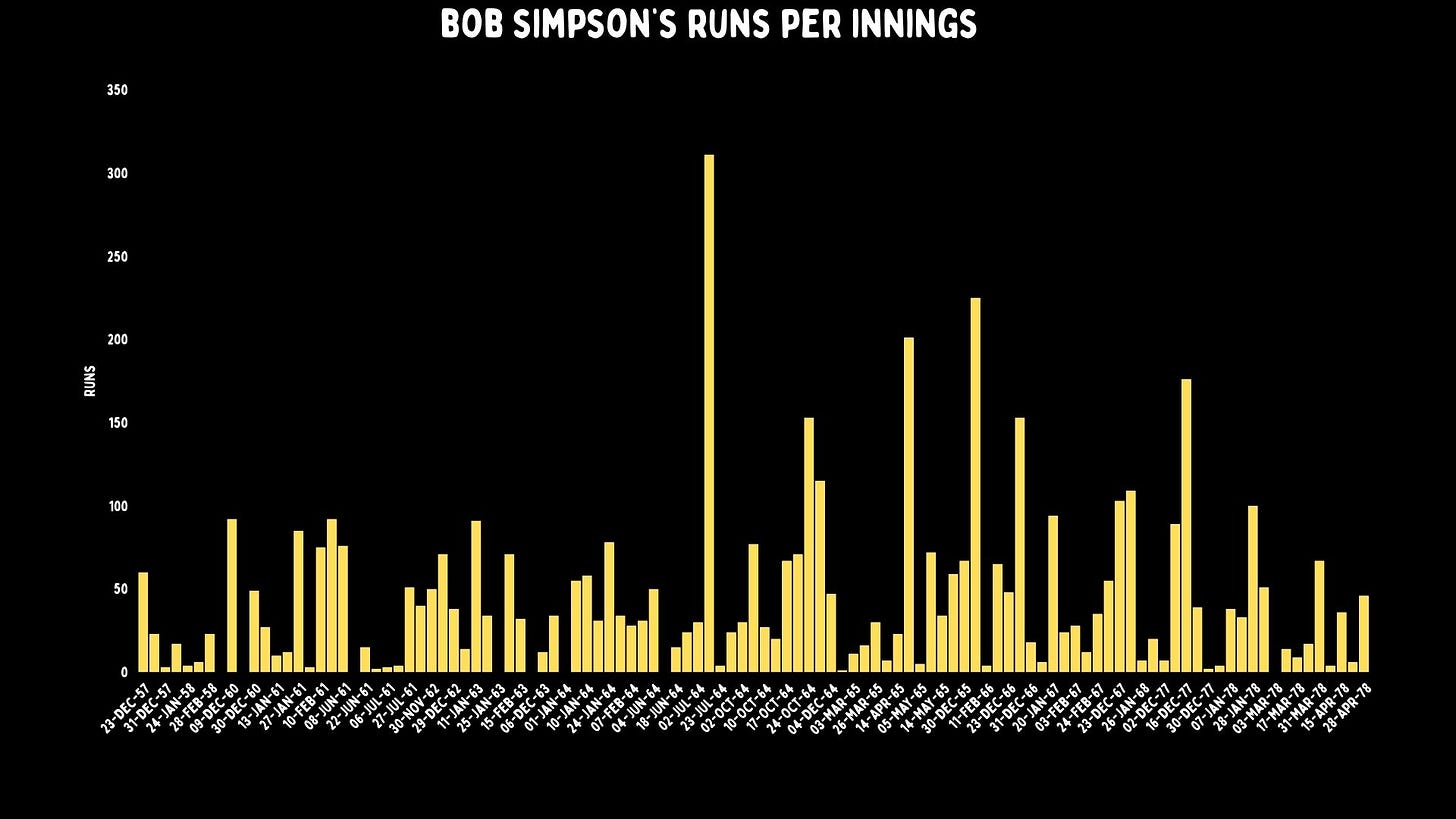

For the longest time, Simpson was ordinary with the bat. Halfway through his career he’d never made a hundred, which is extraordinary for a man who almost averaged 50. Of course, when he did make a ton, he passed 300. He’d been learning, developing and striving his entire life, and all that homework, practice, and fitness finally came out.

For the rest of his career he made a huge amount of runs, and then, at the age of 31– while still in his peak – he retired. He’d achieved what he wanted to, and now it was time for a new challenge. With his skills in the field, he could have played even through a batting dip. Instead, he left mid-career — leaving a hole that no Australian opener has ever really filled since: a captain, a great fielder, and taking a wicket per match.

Simpson was not one of Australia’s greatest players, but he was one of their most irreplaceable.

And his biggest talent may seem mundane: Simpson ran. For his own runs, and everyone else’s. This was more common in Australian cricket early on. But while we called them runs even then, there was plenty of walking, jogging and sashaying down the wicket. Simpson didn’t care if he hit the ball or his partner did, he was running.

However, it was in partnership that he truly advanced the game. When Simpson made his maiden ton, he did so with his great friend and opening partner, Bill Lawry. They put on 201 for the first wicket. And Simpson would go on to make 311 runs. And we do mean runs. Those two players made 417 between them in that game, and only 136 of those runs were boundaries.

Some of this was the left-right partnership, something they were obsessed about years before it was cool. The rest was stealing singles and conning twos. Lawry would be run out for 106. These two ran like modern T20 in Tests in the 1960s.

They played 129 matches between them. Simpson was run out five times, Lawry six. Eleven seemed like a lot, so for the Art of Batting, we looked into it. “Openers in the 1950s and ’60s were usually run out 3.5% of the time, including Simpson and Lawry, who were run out 8.5% of the time.” Yeah, it was a lot.

Chris Gayle had a single run out in 103 matches, Geoffrey Boycott had seven in 108, Sunil Gavaskar had five in 125, Alastair Cook had one in 161, England’s opener Herbert Sutcliffe did it once in 54 and his partner Jack Hobbs had two in 61. West Indian Gordon Greenidge was never run out in 108 matches; his partner Desmond Haynes, six times in 116. This was just a random list of openers I looked at. You can see that what Simpson and Lawry did was nothing like anyone before, or since.

Simpson made runs, by running. And then he walked away.

But one of the most important things Simpson ever did was simply come back.

***

In 1977, the Australian cricket team imploded. The players were superstars, and were being paid less than their friends who worked in offices and as plumbers. It didn’t make sense, so when Kerry Packer came in to get cheap TV content and hang out with the cricketers he’d obsessed over, most of the best players in Australia signed with him.

The board was furious and picked a replacement side. But they needed a captain, someone to sell (which is ironic) to the public.

Simpson had last played for Australia before Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, January 1968. The world had completely changed, but somehow Simpson had stayed the same. To convince him, they even wheeled out Don Bradman, who’d made a post-war comeback ‘for the good of the nation’. It wasn’t quite a tour of duty, but the pressure was there.

Simpson retired at 31 to get a real job, and was now back as a near-volunteer for the Australian team. Almost ten full years after playing a Test, the 41-year-old returned as captain of a gutted team. When it was announced, the press actually cheered. For them, it was finally an adult in the room.

The weird thing about all this is that Simpson had been a professional even when he was an amateur. That was just his mindset, how he went about it. The reason he retired at 31 was that he couldn’t make any money playing for his nation. He had even gone to Packer years earlier, asking him to help fund an end-of-season exhibition league, so the players could make real money from their fame. Yet, now here he was, coming back to protect the terrible system he’d walked away from.

Ian Chappell called him a hypocrite. But these were very different men.

Simpson wanted the players to wear blazers, tuck their shirts in, and stop sledging. Chappell wore jeans, flip-flops, and said whatever the fuck he wanted. The moustached man was a rebel, even when leading the official team. Simpson was the principal, and he was telling the kids that playtime was over.

Simpson once told Chappell to shelve his hook shot. It is the riskiest stroke in cricket, one where a mistake can cost your innings, or your face. Those who play it are called happy hookers, but the name is silly. This shot has no happiness; it’s more in hope.

Simpson was a pragmatist, a man who believed his job was to make every last run. Chappell was trying to make a statement. His hook was a warning: “Come for my head, and you best not miss.” He eventually ignored Simpson’s advice and played what he wanted.

Years later, when he was Australian coach, Simpson would work with Steve Waugh — a man who was part Chappell and part Simpson. Waugh took an age to make his first hundred. He was a good fielder, but a better bowler. But he needed to make more runs. A similar predicament to what Simpson once had.

So Steve Waugh decided to cancel his hook shot, and pruned his game back to the necessities for run scoring. He was never fully a Simpson, parts of Chappell always remained. But he bought into his coach’s style. And Simpson’s influence didn’t stop there.

His career finished — the first time — before ODI cricket or the World Cup existed. So he’s a weird guy to shape white-ball cricket for decades. But as the coach of the Australian team in 1987, he changed our sport forever.

He did something really weird: he took the players out early to acclimatise to the Indian pitches. He also made sure his team was fit, and were great in the field. Running between the wickets would be their superpower when batting, but they had an anchor to keep wickets in hand. They would rely on batters who could bowl spin without a truly great frontline version to bank on. Their seamers were either pioneers of the slower ball, or early adopters.

None of this sounds weird now, because over the decades that followed, everyone copied this blueprint.

Slower balls barely existed — to have three seamers doing it was incredible. Stealing every run was not how the middle overs had gone before; it was mostly knocking the ball to a sweeper and ambling through. Players had roles before, but never as clear as Geoff Marsh as an anchor. A template we still live with. Most of all, the Australians took this seriously when many cricketers of the era still thought it was a joke.

Simpson took an Australian team where their main spinner averaged 50 on Asian wickets, and stole every extra run they could throughout the tournament, ultimately stealing the trophy as well. Along the way he invented modern white-ball cricket, even if Australia won it with the red one.

It was Australia’s first World Cup win, and they’ve won a few since, often using or expanding on the Simpson way.

***

When Simpson came back as a player, the first series was at home against India. He hadn’t played in almost a decade, and yet made 89 at the Gabba in his first match back. Then 176 at the WACA and then another 100 at Adelaide Oval. That would be magnificent for any 40-year-old, but for one who’d been pushing a pen for ten years it was remarkable. Australia — or what was left of them — just snuck by with a 3-2 win. Without Simpson, they lose.

So his next job was heading to the West Indies.

In Australia, he’d handled the skilful seamers and class spinners well. But now he had the West Indies, who may not have always had their best bowlers, but had enough to bowl very fast at this very old man. He got filleted by the West Indies. Passing fifty once in nine innings, and Australia got thumped. But at 3-1 down, they had a sneaky chance of winning a consolation Test to make the series look closer in Guyana.

Australia needed the tenth wicket to win with 6.2 overs remaining. The issue was actually the ninth wicket. The locals didn’t think it was out; the crowd threw bottles and stones so the police said it was unsafe to proceed.

The Australian Cricket Board chose him as a saviour, but his career finished without even being allowed to walk on the ground. He started by being clapped, he ended by being booed.

Simpson’s legacy was almost as complicated. A great batter with a terrible start, who disappeared during his peak, and came back when his team needed it. His batting average of 46.81 probably flatters him, but also says nothing about the way he changed the sport forever.

Simpson was a gut-busting cricketer. For almost 50 years he was one of the most important people in Australian cricket (and then the world game) He was stubborn, believed things needed to be done professionally, and had a dogmatic view of cricket. But whether it be taking slip catches, running hard for his partner, facing the West Indies in his 40s or writing the blueprint of modern white-ball cricket, he did all of it with his chest.

He was one-and-a-half men in the slips, one-and-a-half runs when he batted, and one-and-a-half cricketers for Australia. Bob Simpson changed cricket with his full chest.

Many thanks; I enjoyed this especially the runout stats.

I think you could make a case for Simmo as the most influential Australian cricketer in the last 60 years (or even post-Bradman) with how he established much of the ongoing template for success:

- hard running for singles and twos;

- wider spread of slips meaning more effective coverage and support for pace bowlers;

- proper coaching and professionalisation of the process;

- emphasis of fielding and proper training for it

However, because he chose the ACB rather than WSC in 1977, his legacy has been largely ignored (especially as compared to Ritchie Benaud and Ian Chappell)

What do you think?