Cricket's greatest shapeshifters

A true all-rounder is not just their numbers, it is the effect they have on the entire team.

Buy your copy of 'The Art of Batting' here:

Manoj Prabhakar had incredible hair, and sometimes that should be enough. But he could also play. He swung the ball around a little, even getting reverse earlier than most non-Pakistanis. But he could bat too. In fact, he opened the batting for India. He was a cricketing shapeshifter.

Perhaps his most famous moment in cricket is when he opened the batting and bowling against the West Indies for an ODI in 1994. He got smashed with the ball, but had India within touching distance of a win, when his teammates stopped batting. They needed 63 from nine overs, and according to Prabhakar, he made nine from the eleven balls he faced. At the other end Nayan Mongia was apparently told to get as close to the total as possible. He did this by scoring 4 from 21 balls. West Indies won by 46 runs.

In that match, Prabhakar bowled six overs and made a hundred. He opened the batting and opened the bowling - a player trying to be two forms at once.

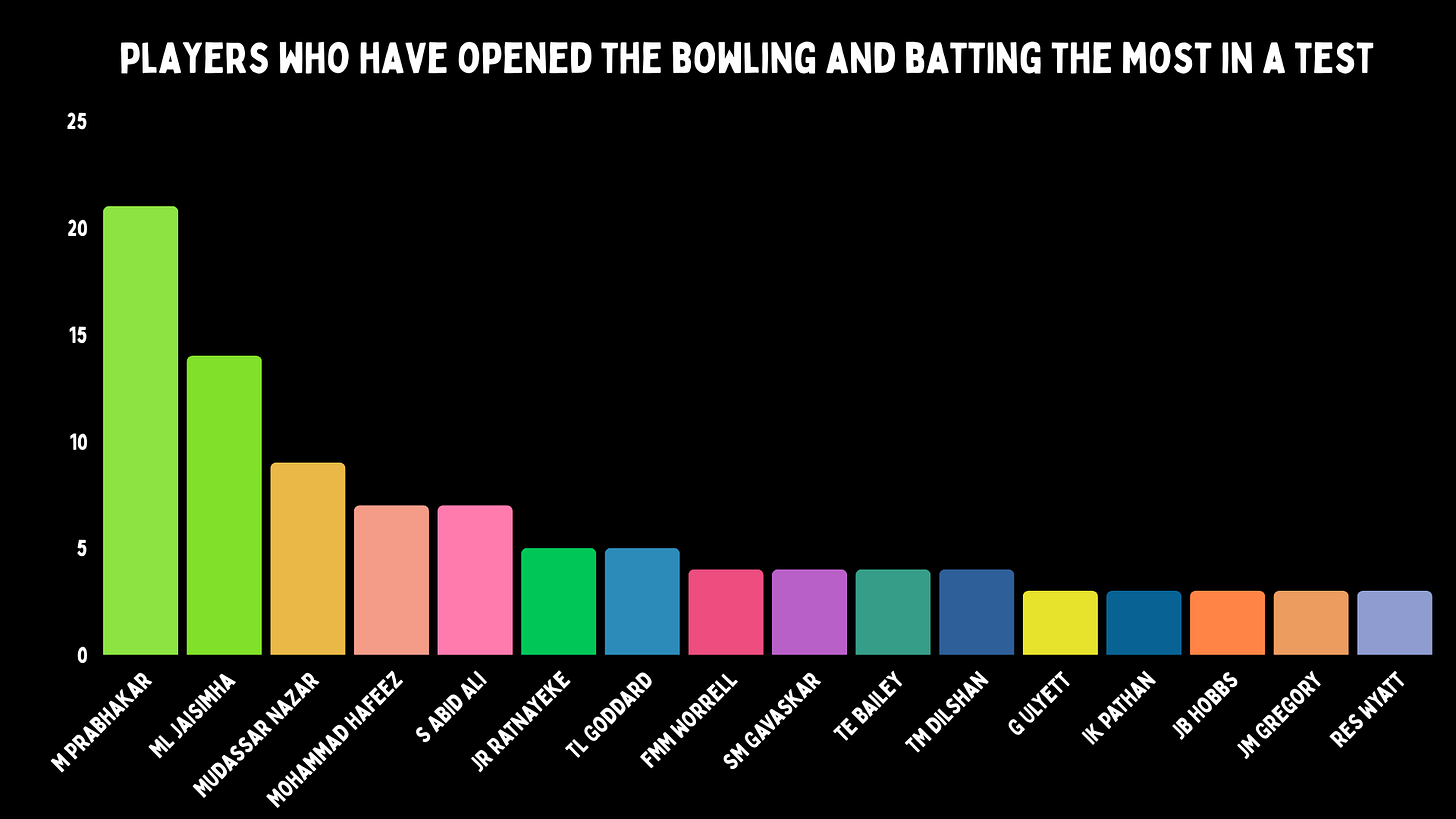

In Test cricket, he has done this 21 times, the next best is 14. It’s really playing underage cricket to do these two things simultaneously. You shouldn’t be doing it in a Test, and so many times is taking the piss. But it gave India incredible flexibility; they got either extra batting or bowling in the team because of him.

But despite his incredible hair, Prabhakar was not great at bowling or batting. With the ball his average was 37, and 32 when batting. Our metrics have him as 8% worse as a bowler than other all-rounders, and 12% with the bat.

Prabhakar wasn’t a great player, but he did give incredible versatility. He was not a great all-rounder, but he was very rounded.

All-rounders are the toughest players to rate. Often their numbers look uninspiring on both sides of the ball, yet their teammates laud them as superheroes. They make an impact beyond their own talent, just by being fluid.

The truth is, for almost every single all-rounder ever, there is a trade-off. Some are great at one skill, but below par at the second. Others are the bits-and-pieces players who are below par at both, but the team likes the overall package. The reason we see so many teams try to find an all-rounder is that they are usually worth more than just what they produce.

They are cricket’s greatest shapeshifters, and this makes it almost impossible to work out their true worth.

If you did a Venn diagram of batting or bowling, the middle section would be for all-rounders. Except, I don’t think any player in the history of the game is good enough at both skills to get all that close.

No one in the world would argue that Ian Botham isn’t an incredible all-rounder. Beefy has 5200 runs and 383 wickets. He averages more with the bat than the ball, and those who saw him, say he could have played for England as a batter or bowler.

The original definition of an all-rounder is someone who can get picked with bat or ball. But is that true? And has it ever been?

Botham is a great place to start. At times he probably was both, but across his career he went up and down. His bowling average of 28.40 is good, but he was only 1% better than the other seamers in his matches - almost exactly par.

Would he have played for England as a specialist bowler? Yes, but not for 102 matches. More likely he’d have been in and out. Yet in the 1980s - when England were awful - you could still argue he was their second-best seamer.

What about the batting? Again, Botham made a lot of runs in the 80s, but others had stronger records. Nine players scored 1000 runs at a better average. He also batted with an all-rounder’s freedom, which probably hurt his numbers. Allan Lamb is the best comparison - he played 57 matches and averaged only slightly higher. So yes, Botham would have been picked as a batter, but not as a regular.

However, only two England batters averaged over 40 in that period. So in that weak era of English cricket, Botham could make it as a batter or bowler. But for huge parts of English history, he wouldn’t have. He really needs to bat at five or six, and with Harry Brook and Ben Stokes at in those positions, he’s not getting in. His bowling might get him picked now, but he wasn’t getting in ahead of Stuart Broad, James Anderson, Mark Wood, Jofra Archer and Stokes a few years back.

In a good Test team, Botham was at best a fringe pick as a batter or bowler. Most strong batting sides wouldn’t need him, and as a bowler, he’d only fit in specific attacks.

Yet I say this about one of the greatest all-rounders ever. Botham was less a specialist than a transformer - bending to what England needed, whether as a hard-hitting batter or a bowler leading the attack. England could change their lineups because Botham existed. He added more runs and wickets just by playing.

But I wanted to check the best three all-rounders in history, and I couldn’t fit them in the middle of the Venn diagram either. Garfield Sobers, Imran Khan and Jacques Kallis are all great at one thing, but they’re not inner circle with their secondary skill.

Sobers was in his late 20s when he started bowling seam. He was a new ball specialist, who of course later in the innings bowled spin. Maybe West Indies try him, but it’s doubtful he’s a full-time bowler. Kallis could bowl, but his average is lower because of the pitches he played on. It’s really unlikely that he’d be a regular bowler in that South African lineup when you had Allan Donald, Shaun Pollock, Makhaya Ntini, Vernon Philander, Dale Steyn, Andre Nel and Morne Morkel.

Imran’s batting was incredible in the 80s, averaging more than 50 for a ten-year period. But would Pakistan have picked a 30-year-old number six who couldn’t make hundreds? It’s really unlikely.

Only Kallis didn’t transform, in a team with loads of all-rounders. Perhaps he didn’t need to evolve. Part of the genius of the other two is they mutated into perfect organisms to bring harmony and balance into their XIs.

And when their numbers look great, they are even more important.

If this is true of the greatest all-rounders, what does it mean for lesser players? Sadly, looking at numbers of all-rounders is much different from doing so for specialist players.

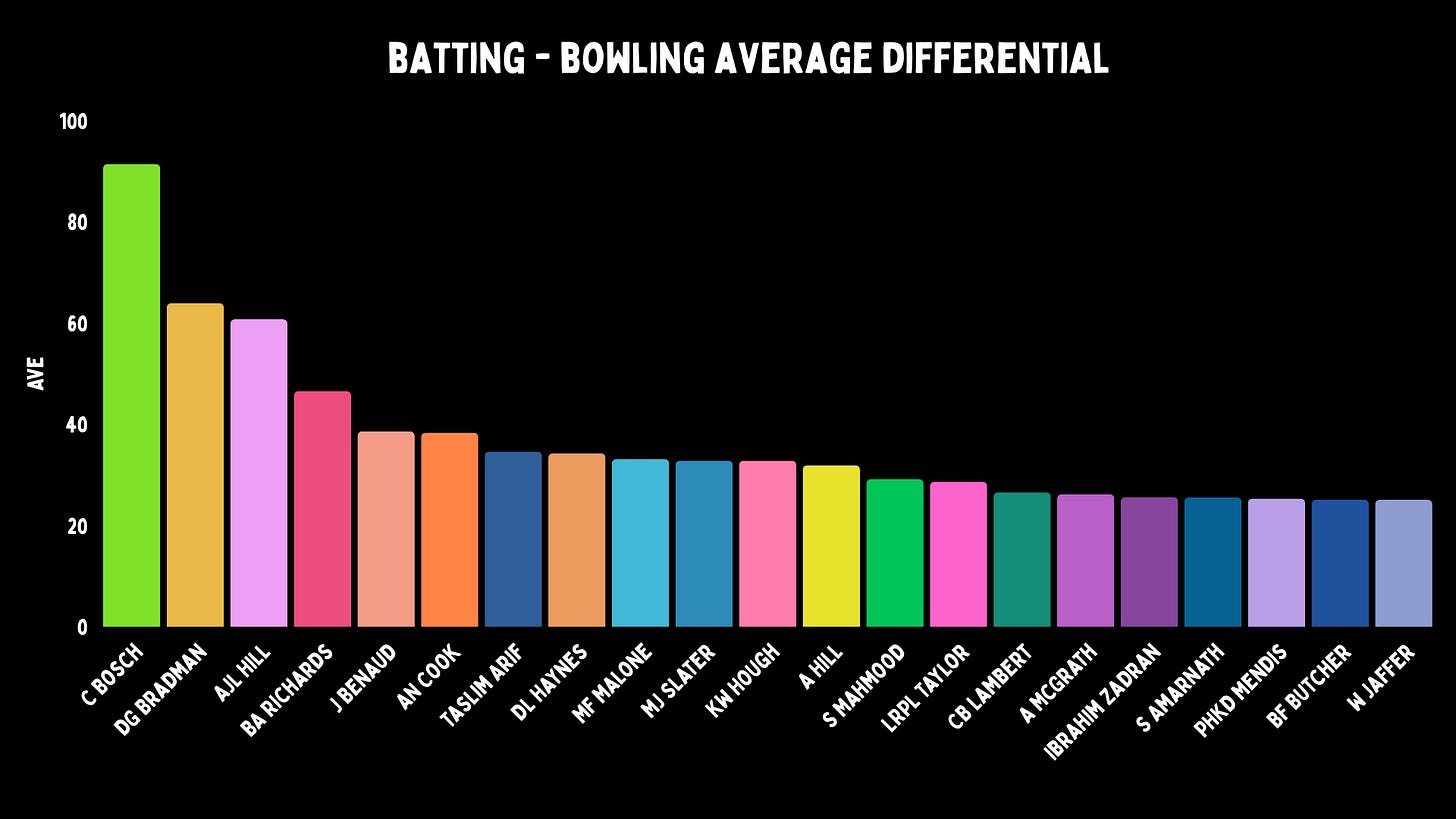

The main stats - outside of raw counting - used for all-rounders are average differentials. Subtract your bowling average from your batting mark, and hopefully you end up with a plus. Then, you’re a great all-rounder. There are many issues with this. However, we should all sit back and honour our new all-round legend, Corbin Bosch.

But according to this, the second greatest all-rounder is Don Bradman, with Alastair Cook’s Bob Willis impression that dismissed Ishant Sharma coming in at number six. And Ross Taylor’s dirty offies at 14. So this list is garbage, and the only way to make it better is to look at real all-rounders.

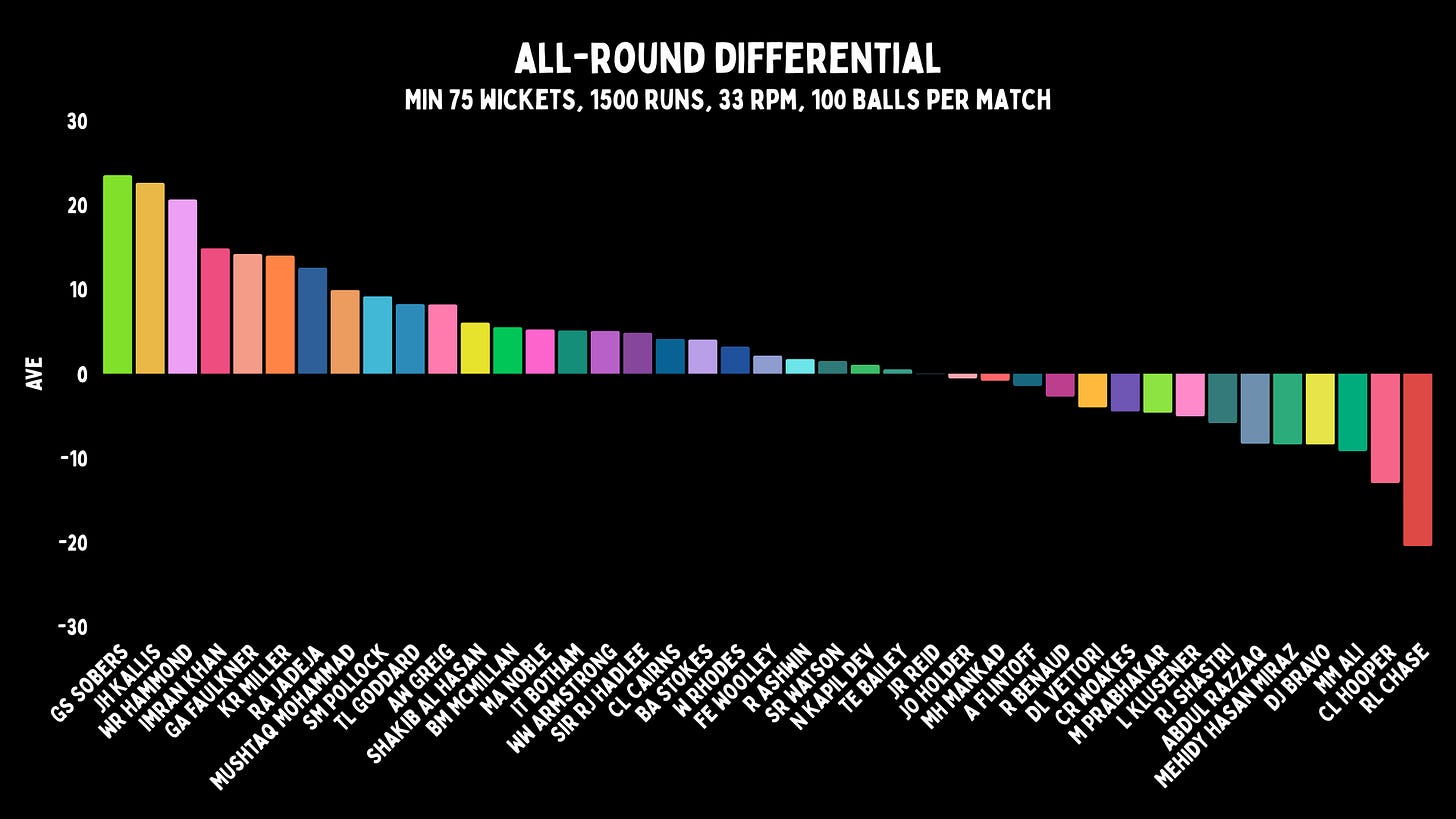

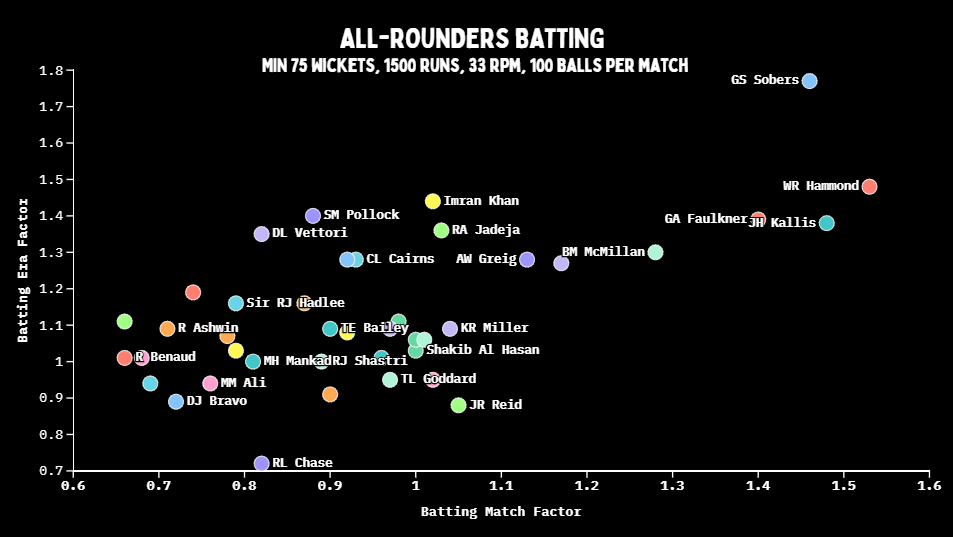

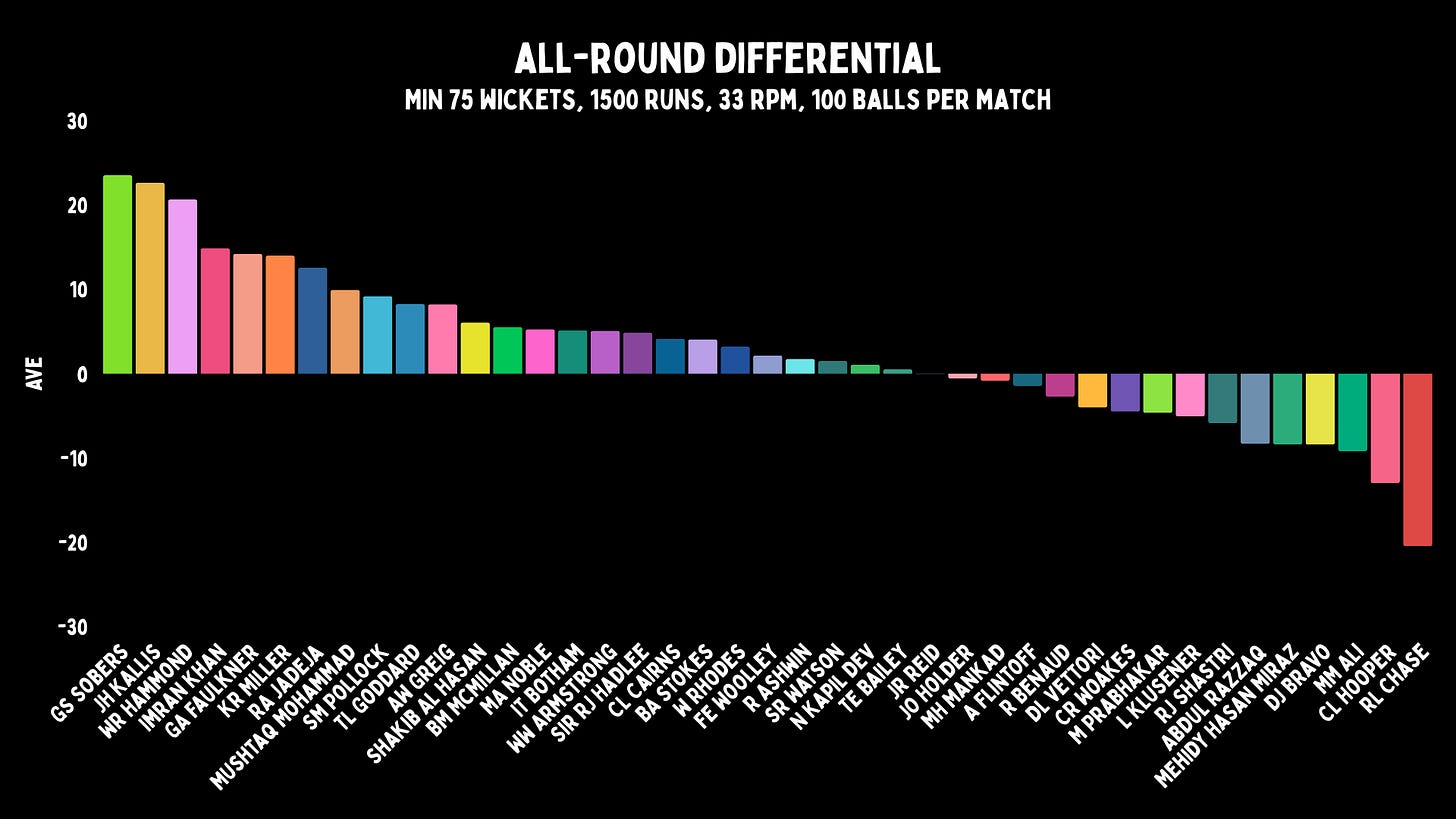

This - and most of the stats we looked at in this piece - has bowlers with 75 wickets while bowling at least 100 balls per match, while also scoring at least 1500 runs, and adding 33 per match. So it should be a better way to see true all-rounders, and not novelty bowlers and batting greats.

And on first look, it’s incredible: look at Sobers at the top (with Kallis and Imran close to him) and Roston Chase all the way at the bottom. That is exactly what you’d expect a list of all-rounders to look like. The two West Indian players should be at opposite ends of this spectrum

However, I want to focus on another player who performs exceptionally well in this metric: Mushtaq Mohammad. On paper, he looks like the eighth-best all-rounder ever. But considering he’s not even thought to be the best player in his own family (hello Hanif), that’s stretching it.

Mushtaq was a fine cricketer, averaging nearly 40 with the bat and 29 with the ball. Those numbers are impressive. He was a skilful leggie with all the tricks - even a flipper - but Pakistan barely used him. He took 79 wickets in 57 matches. He was like the bowler people imagine Joe Root is: a frontline batter who could double as your best spinner.

Look closer and the shine fades. His 29 average was built on dominating a poor New Zealand side; against everyone else it was much higher. More importantly, his captains rarely trusted him. In his first three years, he played 14 Tests as a batter and never bowled more than six overs (also barely bowling domestically). A frontline spinner delivers 35 overs per match (or 213 balls). Mushtaq only bowled that many in five of his 57 games.

The only captains that trusted him were from his own family, Hanif and himself. It was also a strange era. One of his captains, Intikhab Alam, was another legspinner who batted. Intikhab was picked as a bowler from the start, while it took years for anyone - even in domestic cricket - to give Mushtaq the ball. Most of his wickets were playing county cricket for Northants.

If Mushtaq had been forced to bowl frontline overs, his average would almost certainly have risen. The truth is, his record flatters him. However, he was a talented cricketer who grew into his second skill late, but never got to bowl enough to make a huge impact.

Shane Watson is another player like that, though his story was written by his body. A young Watto was genuinely fast, and if not for constant omnipresent niggles, he might have been Australia’s best all-rounder since Richie Benaud. Instead, he became an S-tier Paul Collingwood or Sourav Ganguly - medium-paced, clever, accurate swing, but hardly scary.

How good was he? Well, by the differentials, Watson appears slightly positive overall, while Indian legend Vinoo Mankad appears slightly negative. But that hides their actual shape.

Watson gave Australia around 63 runs and 100 balls per match. Mankad gave India 47 runs but a gargantuan 333 balls.

Watson gave you par batting and useful bowling, but not a true five-man attack. Mankad’s batting was slightly weaker, but as a genuine frontline bowler he gave India far more chances to win.

It’s a question of what shape your team needs. One was efficient, the other transformative. Watson helped if your team had four frontline bowlers who just needed rest. Mankad transformed the team, giving them the option for five frontline bowlers or deeper batting. Watson added, Mankad reshaped.

Just on batting, Watson and Mankad aren’t far apart when adjusted for match and era. The metric is flawed, as it rewards position more than production. Sobers looks better because he batted at six; Kallis and Hammond worse because they sat in Sachin and Bradman’s shadow. Aubrey Faulkner batted everywhere and still outperformed his peers by 40% in his matches.

When we talk about the greatest all-rounders, he comes up a lot. Because he’s the only player in Test history to make 1000 runs and take 50 wickets while keeping his batting average over 40, and his bowling under 30.

His bowling record is fantastic, but when you look at the advanced numbers, he was about a par bowler (albeit with moments of genius) rather than a star.

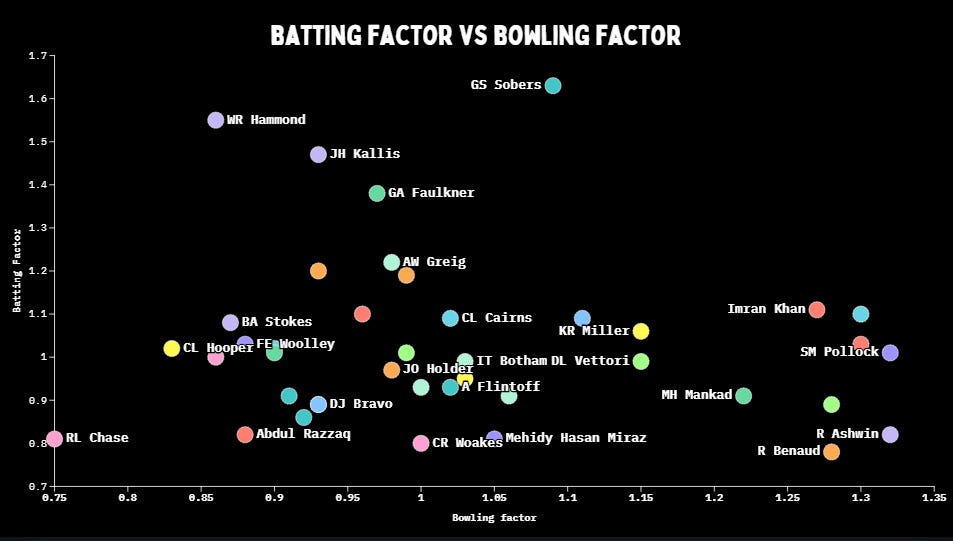

Whereas there is a group of bowlers here who are all obviously S tier: R Ashwin, Shaun Pollock, Ravi Jadeja, Imran and Richard Hadlee. None of the great batting cluster is here. And that makes sense, as the chance of you being elite at both is almost impossible.

However, these numbers are about evaluating the quality of the player, as if they were a specialist. Take Trevor Goddard’s batting: it’s not great, just marginally above par. Which was fine, because he was a bowler too.

By being serviceable with the bat, South Africa could field an extra bowler. And his seam was excellent - three wickets per match at 26, sometimes even opening the bowling and batting like Prabhakar. The team lost little with the bat, but gained a lot with the ball - similar to Mankad.

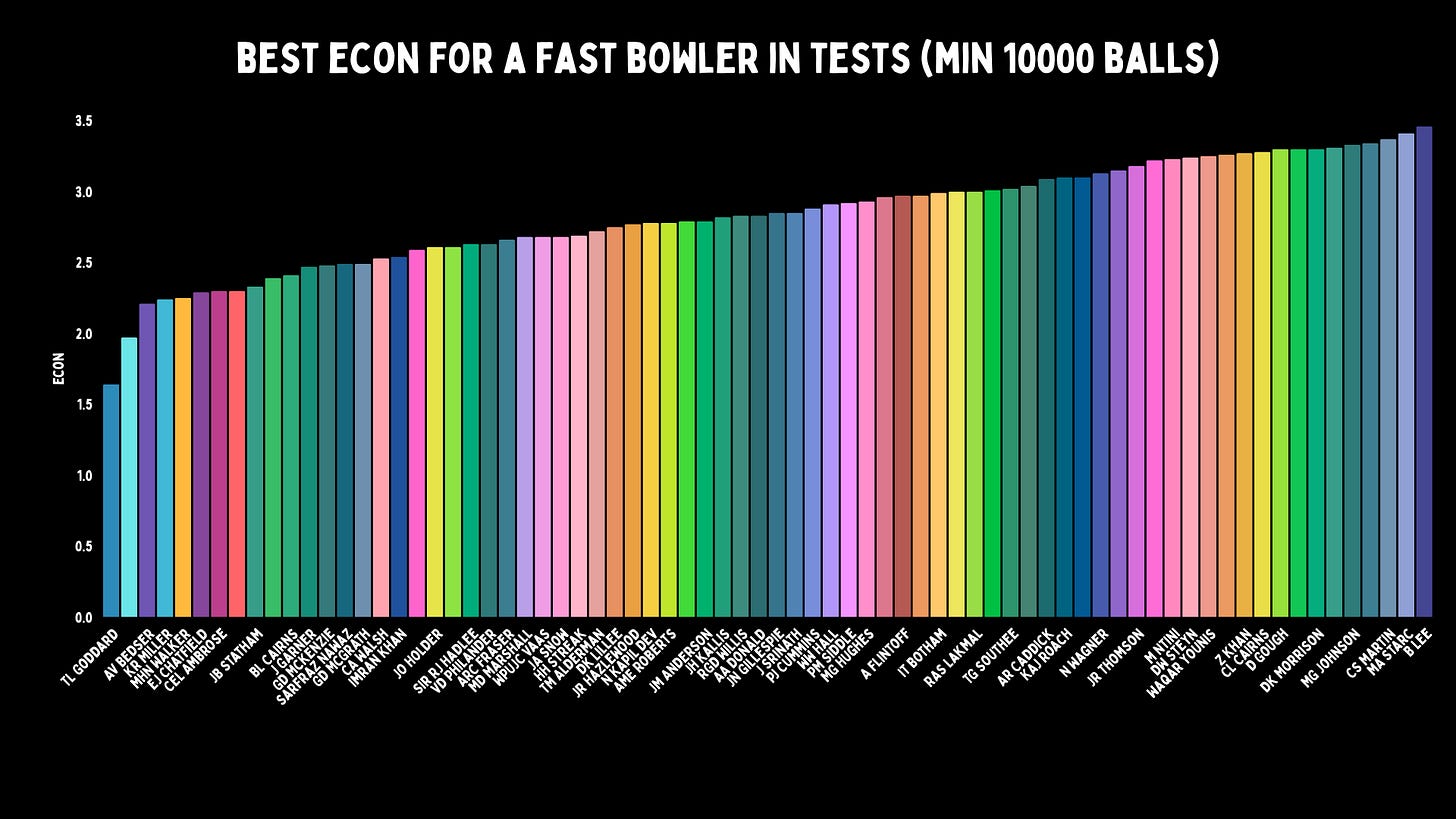

Despite his numbers, Goddard wasn’t a conventional frontline bowler. He was a genuine freak of his time: a left-arm medium pacer who bowled round the clock and was as defensive as possible. Less a bowler than a dam - holding games until they reshaped around him.

When we say defensive, we’re not kidding. He took a wicket every 95 balls. No other seamer with 100 wickets has gone worse than 84. Almost sixteen overs per victim.

Why did he bowl so much then? Because his economy was the best of any seamer with 10,000 deliveries. Only one other went under two runs per over, and Goddard is miles better. Batters struck at 27 against him for 41 Tests, home and away.

Adjusted for era (and his was slow), he was 48% better than par at run prevention, and bowled the third-most deliveries per match (behind only Benaud and Mankad) on our list. He bowled endlessly, no one scored, and sometimes wickets came too.

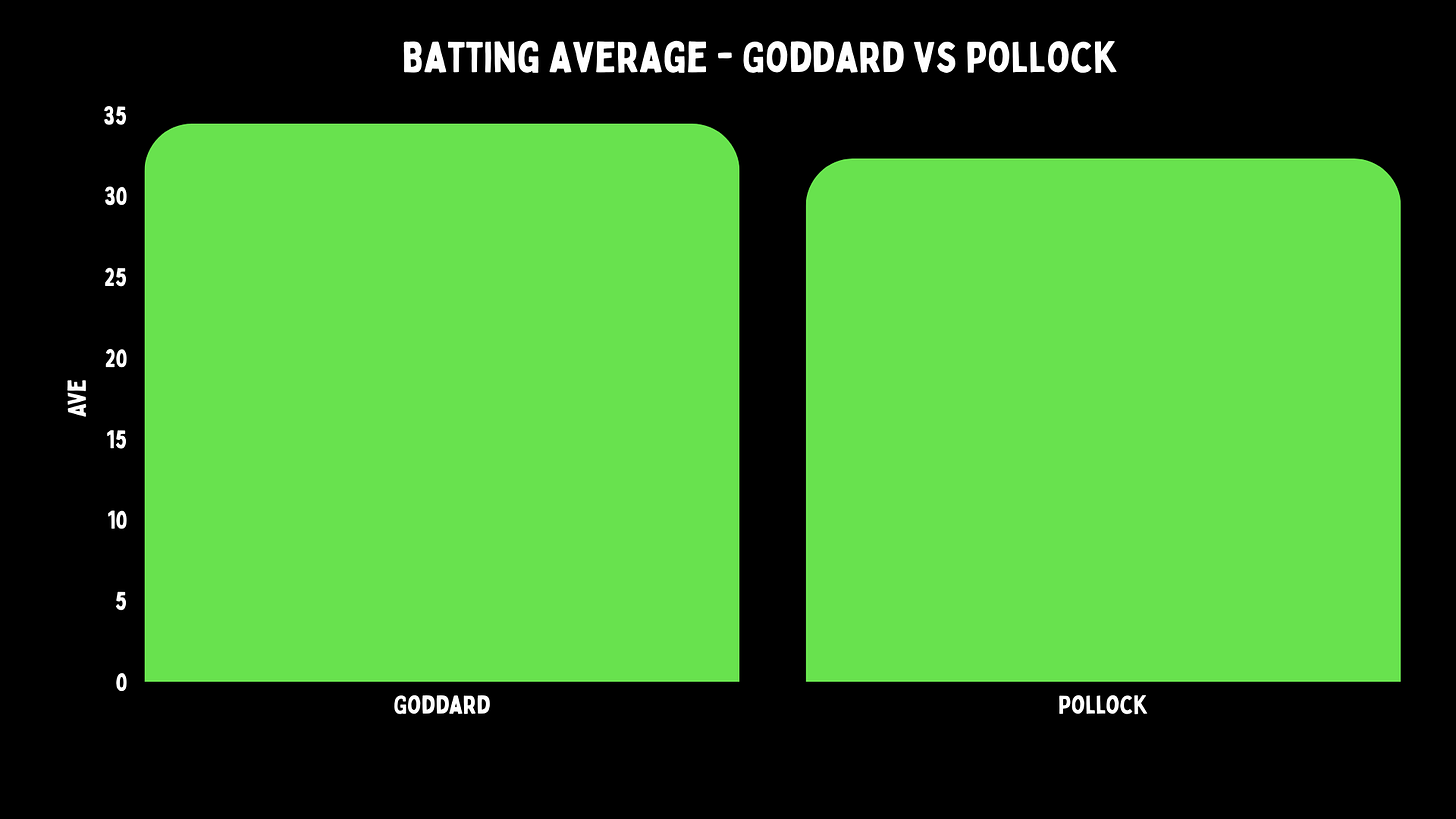

Still, you probably wouldn’t pick him as a specialist. Too slow with the ball, just passable with the bat. Compare him with Shaun Pollock - another South African seamer no one scored off. Pollock was great; if you were picking tomorrow, he beats Goddard.

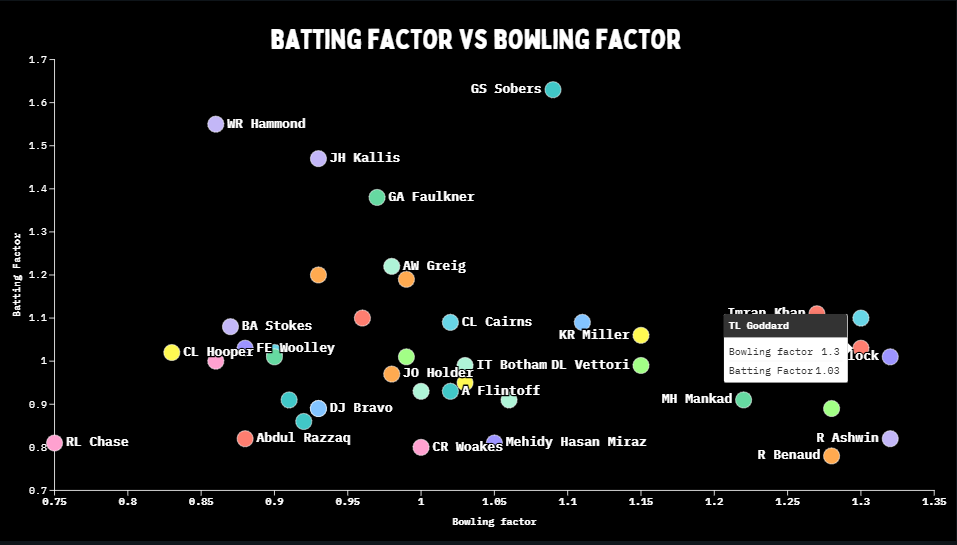

This graphic combining batting and bowling has flaws. It lacks batting strike rate and loves Goddard for his economy and endless spells. But it shows they are side by side.

There also isn’t much between them with the bat; Goddard has a slightly better average.

The real difference is where they came in. Pollock was a number eight (really a seven), Goddard an opener. Pollock would’ve been under par at six, but Goddard was slightly above par at the top.

Structurally, Goddard let South Africa play five bowlers without losing batting. Pollock gave strength at eight, helping teams not lose, but not increasing winning chances much.

At seven, Pollock only really transformed a side if the keeper was a good batter, or if another all-rounder was present. To add a fifth bowler consistently, your all-rounder must hold down number six or higher. Perhaps Pollock could have done that, but South Africa’s team never needed it.

A number eight who bats is useful, but not transformative. It works the other way too. Bat top six but barely bowl, you’re not much use.

By differential, Wally Hammond is the third-best all-rounder ever. But he bowled under 20 overs a match, took less than a wicket per game, and hardly changed England’s chances to take 20 wickets. Handy, but not transformative.

The best all-rounders allow you to add a bowler without weakening the batting much. That’s the magic equation. Goddard is structurally more “round” than Pollock, even if Pollock was the better cricketer.

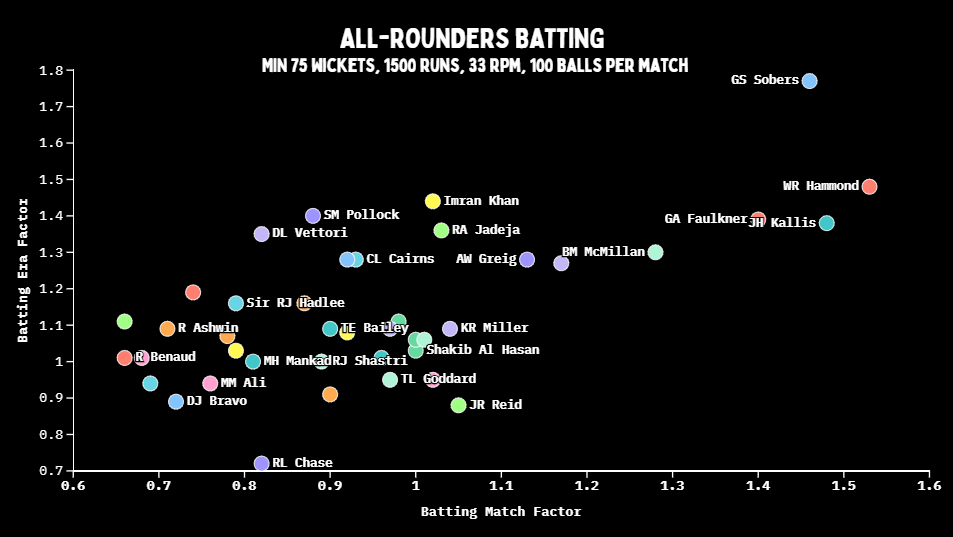

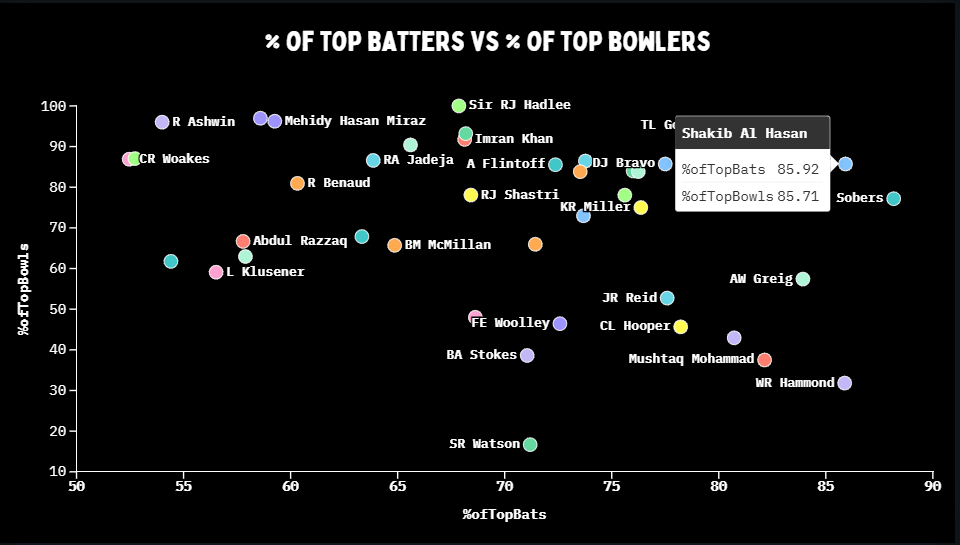

But how do we show this? At first we wondered if it might be useful to look at our players by their batting and bowling ratings. And there should be a few players in the top right. But there aren’t.

Maybe this is the empty part of the Venn diagram.

There are players who are above par in both metrics, even if just. A few incredible players miss out, like Faulkner, Kallis and Kapil Dev. Great all-rounders, but not great all-round. Botham, Dan Vettori and Warwick Armstrong miss out by the barest of margins.

But the players who are above par on both our metrics are: Chris Cairns, Shakib Al Hasan, Keith Miller, Pollock, Goddard, Imran, Sobers and Jadeja.

This feels like a step in the right direction, but it also contradicts what I said about Pollock. He is the only one here who doesn’t quite make sense. So while this helps, we know it’s a little flawed for our end goal.

We need people in the top right corner.

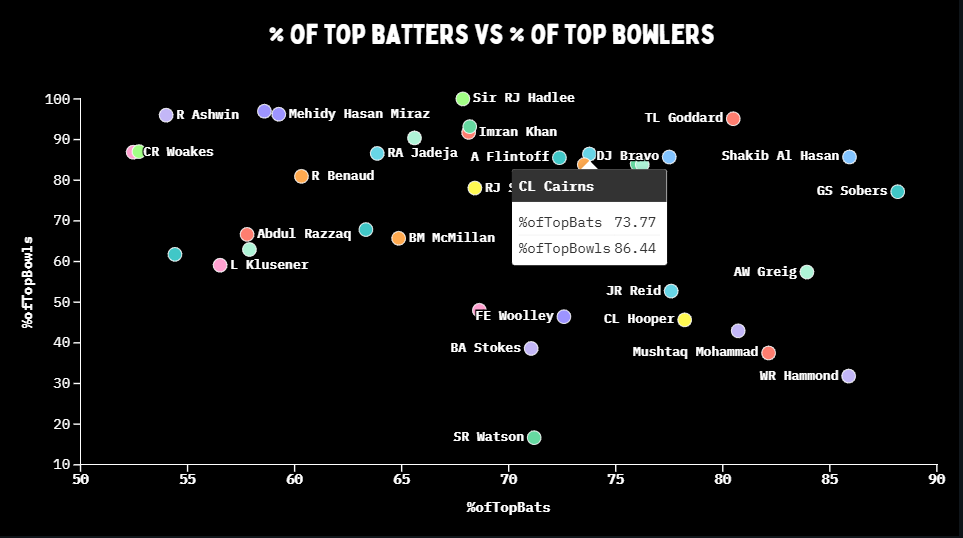

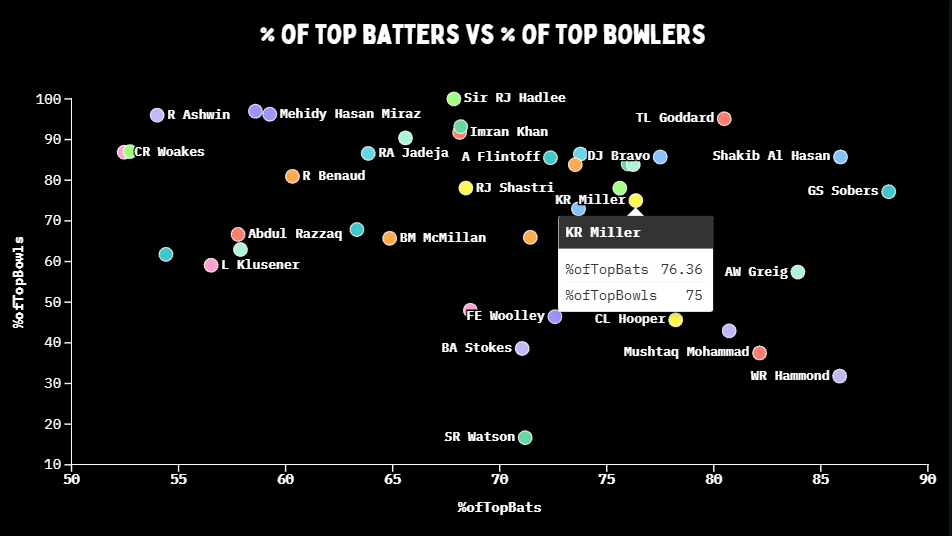

So we came up with something else. This is the percentage of times a bowler delivered the ball enough to be in the team’s four most-used bowlers for a Test. And this is also looking at the percentage of how often a batter was in their top six run scorers (because we don’t have balls faced by everyone).

Now we have clear standouts in the top right, and plenty of other great all-rounders take a step back because they’re simply not used enough, or just handy with their second skill.

Pollock, Jadeja and Imran all take a step back here, because they batted low for long periods in their careers. Whereas Miller and Cairns were frontline bowlers and top six batters - closer to the magic zone.

But it’s clear we have three standouts here when it comes to roundedness.

No one was rounder than Garfield Sobers. He bowled so much late in his career that he overcame the fact that for the first eight years he never took more than ten wickets in a year. In 1969, they made him bowl 50 overs per match. He was also the world’s number one batter at that time. In 15 Test matches in the three previous years, he averaged 86.65.

So he makes sense, and so does Goddard. But both of these players lean one way - Goddard toward bowling, Sobers toward batting.

Shakib, though, is almost perfectly balanced. In 85% of games he bowled a frontline load, and 85% with the bat he added top-order runs.

The only others with numbers that even out like that are Miller, Brian McMillan and Prabhakar, the man who played Test cricket like it was under-13s.

Shakib is the most evenly rounded all-rounder ever when we look at what he produced for his country.

If we look at his efficiency and advanced numbers, he’s around 10% better than his peers with the bat, and almost par with the ball. But like Botham, he wouldn’t make every side as a specialist.

In stronger batting lineups he might slip to seven (like Jadeja or Vettori), meaning he’s not quite a specialist. With the ball, he’s Bangladesh’s leading wicket-taker, yet his record is eerily close to Taijul Islam’s, and not far from Mehidy Hasan Miraz. He might have struggled to get picked away from home if he couldn’t also bat.

Let’s imagine he played for other teams. For India, his bowling wouldn’t cut it consistently. He wouldn’t have played over Herath in Sri Lanka. Lyon or Maharaj? That’s at least debatable.

But that doesn’t change how special he’s been for his nation.

What Shakib shows - and what most true all-rounders show - is that having two skills changes the whole shape of your team. At one point, Bangladesh carried a specialist number seven who only batted, because Shakib gave them a frontline bowler higher up. They’ve regularly gone in with five bowlers, and still do it now with Mehidy. For Bangladesh, who have struggled to find specialists, Shakib was the cheat code to patch up their broken system.

If Bangladesh cricket had a Venn diagram, he would be in the centre, but not for every team. But as an all-rounder, your job is only to make your team better.

England used Ben Stokes and Moeen Ali as a combined frontline bowler to give themselves five options with the ball, and more batting. Pollock, Kallis, Klusener and McMillan did a similar thing for South Africa around the turn of the century.

A true all-rounder is not just their numbers, it is the effect they have on the entire team.

Manoj Prabhakar was what we’d call now a bits-and-pieces cricketer. He wasn’t quite a batter, and not quite a bowler either. India were more likely to pick him away from home, when they needed more seam. His being chosen meant they could use an extra batter when going for a draw, or an extra spinner, without ruining their lineup.

In fact, India often played three of their all-rounders at once with Prabhakar joining Kapil and Ravi Shastri. They didn’t have a team that could take 20 wickets away from home, but they could use Kiran More - their keeper - at nine to help draw matches.

Prabhakar’s average differential is –4.65. However, the extra batting and bowling in the team was worth more than that. Like most all-rounders, he was given jobs he wasn’t really up to, and yet he did his best, so that other players could prosper.

All-rounders are not just the runs and wickets they make, they’re also the runs and wickets others make because of them. As Bruce Lee said, “Be water, my friend.” A successful all-rounder will usually start as one thing and finish as another. Their shape doesn’t matter; the team’s does. They’re not round at all - they’re liquid.

Good analysis, many thanks. One factor you’ve looked at for batsmen in particular might be useful here; peak years performance as it helps to reflect when a player was at his best and takes out early and late career blibs.

I’m slightly biased because, having watched Sobers I’m convinced he is the greatest but as rolling, say, 5 year analysis would be another fascinating way to answer the question of the best. Sobers in the mid 1960s would be my guess