How Cricket World Cups were built

An ad-hoc collection of schoolgirls, mums, sisters and die-hard amateurs gifted the sport something it never had: a global showcase.

Buy your copy of ‘The Art of Batting’ here:

Less than an inch.

That’s how much column space The Daily Telegraph gave the first-ever cricket World Cup match.

In 1973, New Zealand were heavily favoured against Jamaica, having beaten them in a warm-up. The game was supposed to be on the iconic Kew Green, a beautiful place to start a huge movement in the sport.

But it pissed down, and no one turned up.

The newspapers, which had barely been excited in the first place, didn’t cover the washout. There were no think pieces about how unfortunate it was that cricket had come up with this international carnival, and on its first day, it was flooded - with no one there to notice.

Day 1 of the Cricket World Cup concept was an utter failure.

The event wasn’t generating much buzz beforehand either. County cricket and the touring New Zealand men’s team got the attention. Wimbledon was coming soon as well. When the press did show an interest, it didn’t always go well.

Frank Keating in the Guardian wrote that photographers went to the nets hoping to get upskirts of the bowlers.

Lord’s didn’t allow women to play there, despite hosting schoolboys and celebrities. Even when they just trained on the nursery ground, it made news.

The reason there were no matches at Lord’s was the MCC couldn’t work out where women would get changed - they wouldn’t be allowed in the Members Pavilion because of their lack of penises. Billie Jean King won at Wimbledon that year; it was remarkable that they found a locker room for her.

Cricket and media didn’t care, or mocked them. Major grounds weren’t used, TV did not see this as something worth covering, and it was being run by amateurs who’d never done anything like this before.

This was cricket’s first global tournament, and no one was watching.

But because of these women, and one filthy rich man, the sport changed forever. No one at the ground in Kew Green could have known that they were building a billion-dollar industry.

Inch by inch.

***

The Women’s Cricket Association was formed in 1926, largely by ladies of leisure. The one percenters who had enough money, time and clout to play cricket. It was a very amateur sport, with infrequent series between Australia, New Zealand, and England. Married women weren’t always allowed to play (how could they possibly leave their families?). Smaller grounds were used and radio didn’t broadcast the vast majority of their matches.

More than 40 years later, a 1969 UK Sports Council report declared women’s cricket was “dying.” There were good reasons for this: the matches were falling off, money wasn’t coming in, and when they played, the crowds were almost non-existent. There is an adage that you should never fight with someone who buys ink by the barrel. Women’s cricket barely got a thimble’s worth. Entire matches given an inch or less of column space.

It wasn’t about to grow like Women’s Tennis. That looked almost impossible. The Women’s Liberation movement was not coming to cricket. It was an isolated amateur game in obscurity.

Yet in the middle of that, something bizarre happened: women’s cricket shot for the moon.

And their astronaut was Rachel Heyhoe-Flint.

She was living in a world where newspapers would describe her as “Hazel-eyed Rachael, an attractive and sharp-witted little number of 34”.

All this while, she was a legend who hit the first six in Tests (and ODIs). Batted for 521 minutes to make 179 against Australia at The Oval to force a draw (a world record at the time). Averaged 45 in Tests with three hundreds. And when she retired after a 19-year career, she’d made 33% more runs than any other woman. She was the cricketer of her time. And up until recently, of all time. That is just on the field. Off it, she was the first woman inducted into the ICC’s Hall of Fame and one of the two first women appointed to the board of the ECB. She became a House of Lord’s peer, a baroness. She was on the board of Wolverhampton Wanderers and was one of the first-ever female sports commentators. I could go on.

So, while women’s cricket was dying, it had in Heyhoe-Flint a voice, an activist, a journalist, and a star.

This was also concurrent to the very idea of ladies or girls cricket being a controversial topic (Len Hutton once said of it, “absurd, like a man trying to knit”). Or it was simply laughed at.

The words spoken about it were truly bizarre. Keith Miller wrote in the Daily Express, “Gone were the days of flat chests and hairy legs. These girls had curvaceous figures and beauty... My vote for the cutest-looking cricketer goes to opening bat Donna Carmino, a 16-year-old schoolgirl from Trinidad.”

Amongst the many things wrong with this, the fact he adds she’s an underage schoolgirl is really messed up.

Because of the era and chat about tennis, England captain Mike Brearley suggested that the women could go up against the men in a battle of the sexes type game. Heyhoe-Flint took that and spun it into PR. She was as good with the bat as she was at playing the media.

But what her and women’s cricket couldn’t do was make any money. Enter one of England’s maddest millionaires, Jack Hayward. Or as he was known, Union Jack.

This was an eccentric millionaire who bought islands and saved old boats and planes for the British people.

He also said, “If I had my way, I’d form my own party far more right-wing than Margaret Thatcher. I’d bring back National Service, the Scaffold, the cat o’ nine tails, the Empire – places like Sierra Leone and Nigeria were so much better off under British rule than they are now.”

Someone talking like that is not a person you assume is going to be pushing a progressive cause. Hayward is about the most unlikely ally to the women’s lib movement.

But he really adored Heyhoe-Flint, so at his Sussex home in 1971, they smoked cigars and sipped whiskey while discussing how to make women’s cricket bigger. At one stage, late in the night, Heyhoe-Flint suggested that they could try a Women’s World Cup. It was an idea that had been whispered within men’s cricket, but nothing more.

The timing was important, England had won the men’s football World Cup in 1966. So the country had World Cup fever, and Heyhoe-Flint and Hayward were both football fans. The idea was born.

Heyhoe-Flint was known for being very persuasive, and she must have been, to convince the Empire mad millionaire to spend all of his money on bringing in women cricketers from around the globe. Hayward didn’t even allow foreign cars to come on to his estate, yet here he was planning to bring women in from around the world.

Quite a turn for a man who also said, “I imagined myself as the Cecil Rhodes of the 20th century.” But Jack was clear, ‘I like women, and I like cricket.’

And from that problematic statement came cricket’s first World Cup.

Heyhoe-Flint was clear it wouldn’t be cheap, she was a pragmatist, and knew her sums.

Hayward’s reply: “So what, I’m a millionaire.”

He dropped £40,000, which in today’s money is around 600k, so just shy of a million USD. It is not a huge amount, but it’s a lot when you think this wasn’t an investment; it was purely a donation. And it wasn’t going into a well-oiled machine, but rather an amateur group that, in their history, had never seen money like this. For Hayward it was a few inches off his pile; to women’s cricket, it was a mountain of cash.

His donation gifted us World Cups.

***

This was a DIY tournament; there was no structure or template.

The idea of a global tournament was awesome, but women’s cricket didn’t have many teams. It was still basically three nations - England, Australia and New Zealand. India and Pakistan had not played a Test, and the West Indies hadn’t formed yet.

This is where the organisers just made sides happen. They invited two teams from the Caribbean - Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago. Then they put in a Young English XI to flesh out their fixtures. And finally, they chose an international XI.

That might seem weird, but even the first men’s World Cup had an East Africa side. With the West Indies, cricket was used to assembling teams. It was like someone adding a few inches to their height for a dating profile.

But the international XI was more than a white lie - though the white bit was important - as they were South Africa, without the name. With global politics shunning the Apartheid government, the organisers couldn’t bring in the South African team, so they improvised.

In Raf Nicholson’s book, Ladies and Lords, she has a chapter called “Who are we… to tell the South Africans How to Run Their Country”. That is a quote from Heyhoe-Flint, someone who knew enough about politics and had been over to see what Apartheid really meant. Yet, it was her decision to try to get South Africa into the tournament by rebranding them.

Heyhoe-Flint is a hero and a pioneer to cricket, but here she was just wrong. Sadly she never saw (even for years after this) that what she was doing was akin to the men who thought the women shouldn’t play cricket.

And she also risked the thing she loved. In trying to get South Africa into the tournament, she almost brought the walls down on herself.

Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago were prepared to pull out of the tournament if the South Africans remained. They made the right call, and without those sides, there wasn’t much of a global footprint, so Heyhoe-Flint and the organisers relented. The International XI was reborn and filled with random women who hadn’t been chosen for the other main sides.

This means that the first World Cup was played by three Test playing nations, two first-class teams that would later merge, a young XI, and leftovers. Like building a house from whatever you find discarded on the street.

***

The key part to making this tournament work was going to be the cricket.

On the 23rd of June, three matches were played.

At Dean Park in Bournemouth, Young England’s top-scorer was extras with 12, and they didn’t have a batter pass ten. Australia fell to 9-3, before not losing another wicket. Not an ideal match.

At Hove, England smashed 258 in their first innings. The opening partnership was 246 (still a record today) when Lynne Thomas was run out at the death for 134. Enid Bakewell brought up her hundred as well. The international XI had no hope.

Three huge wins for the best teams. Not a contest among them.

Better cricket came soon though. At Chesterfield, New Zealand batted first against the international team. They made 136, but while their opposition was a collection of random players, one of them was Audrey Disbury, who played for England over a 12-year career. When she was out for 44, the score was 64, meaning they were basically halfway there. But the international allsorts kept losing wickets. At 126/8, they had 4.1 overs to get the remaining 11 runs.

And somehow they do it, pulling off a huge upset in a thrilling match from the last ball. The papers went wild with their coverage. Well, I can assume they did, this was the biggest ‘match report’ I could find.

The game of the tournament, and probably an all-time classic, was the West Indies derby, Jamaica vs Trinidad & Tobago at Ealing. According to the Middlesex County Times, the standard of play was very reasonable.

Which is bizarre, considering this game was nuts.

Jamaica lost their second wicket in the 15th over. They had scored 13 runs by then. Their middle order actually did some damage because of an attacking 16 from Ellicent Peggy Fairweather, who if nothing else has a spectacular name.

For T&T, Jane Joseph took 2/14. I mention her in part because this is one of my favourite cricket photos ever. A full swing of the bat, brilliantly shaped afro, a pig-tailed fielder, random cars and buildings in the background. This was at Fenners for T&T’s match against Young England. But it really shows what we are dealing with; it is not one-day cricket or a World Cup like we know it.

It is not the only cool photo of Joseph I found from that tournament.

Of course, all we have is a few photos and one really good report, as the Guardian sent their Hockey writer Nancy Tomkins to the ground.

Jamaica made a very gettable 97 in 51.5 overs, but started strong in the field, running out a T&T opener with the score on two. That started a collapse as they slid to 10-3, before Louise Browne took over.

You need to know an awful lot about Browne; her sister Beverley played for the West Indies, another sister Ann captained them, and even her mum played against England once. And as for Louise, she was the first West Indies captain.

She could play, and that was lucky for T&T, because they were in a bad way, especially when Louise’s sister Beverley was dismissed for 19. They lost two more batters with the score on 93, meaning they required five runs to win, with two wickets in hand.

Browne brings up her 50, but finds herself stuck at the wrong end. Jeanette James - their number ten - is on strike to Leila Williams, a future West Indies player. With plenty of time left, it was probably worth James (who still hadn’t scored) blocking it out for Browne to come back on strike.

Instead James swings hard, like a proper number ten. But she gets an edge and the ball flies up in the air on the offside. It will be a simple take so James decides to walk towards the pavilion. She turns as the catch is dropped, sees her moment, and sprints through for the winning runs. The cricket version of styling it out.

It might be one of the more ridiculously fun games in World Cup history, and only a handful of people saw it.

Online, there is still almost no footage of this tournament. One of the uploads you can find is mostly on the fact a Royal gave the trophy. But actual cricket footage is pretty slim. They had built a structure, but had no money for electricity, so the tournament was in the dark.

***

Rachael Heyhoe-Flint not only organised and played, but she also reported on the event. That is definitely the greatest all-round effort ever in cricket.

Some of her journalism was bizarre, but this was a weird time in sport. Let alone for feminism.

In early 1973, Tennis legend Billie Jean King had played in the famous Battle of the Sexes match against Bobby Riggs. Then her and other women’s tennis players started fighting for equal pay, which the US Open agreed to that year. (Wimbledon held out until 2007).

Women’s Lib was the term used in many articles about the World Cup, but Heyhoe-Flint was not a bra-burning feminist. And I don’t mention that randomly, she actually wrote that in her Evening Standard piece. At every point, she made it clear she was not about a progressive on any topic, she just wanted women’s cricket to grow.

She had to be a member of the establishment to get into the rooms she did, but while she was a conservative at heart - and politically - she was rebellious in cricket.

And that was not easy.

In one of her articles for the Daily Telegraph, she wrote, “England’s games are at Hove, Exmouth, Bradford, Ilford, Wolverhampton and Edgbaston.” There were also matches in Bournemouth, St Albans, Tring, Chesterfield, Sittingbourne, Ealing, and Dartford.

If you’re a cricket fan, you’ll probably realise these are not really big name venues, outside of Edgbaston. That was a problem for women’s cricket from the start. Some of these places were beautiful grounds, but the facilities were not always good.

England women did play at the Oval that year, but not in the World Cup, instead it was against an old England XI. One of the promo photos is Denis Compton leaning in to suck the soul out of Heyhoe-Flint through her mouth. So when it was to watch a geriatric Len Hutton push through the covers, the England women got a big ground. To play in the World Cup, it was Ilford and Exmouth.

They were trapped in small venues, with a non-existent marketing budget, no real help from newspapers, TV and radio - which meant that for most of these matches, hardly anyone turned up.

One of the games was in Bletchley, right around the corner from where the Enigma machine was invented. During World War II, this was one of the most secretive places on earth.

Down the road 28 years later, they were trying to make a global showcase. Instead, they had one of the most invisible World Cups ever.

***

Wet conditions marred this tournament. Some of that is bad luck, but there were things that wouldn’t have affected the men. Many of the women didn’t own spikes, and as there were small venues, drainage and ground staff were poor.

You can only work with what you have, and the organisers were trying to make magic out of club venues and English weather.

When it was wet, it took longer to clear it up, and then the women had to run in to bowl without spikes on a damp surface. The umpires made harsh calls on whether the games could go ahead, so matches had to be abridged all the time.

With all that in a limited overs tournament, you really need a great system for shortening matches. They did not have that.

Most of us have grown up on the Duckworth-Lewis Method - a flawed yet useful system to ensure that limited overs matches can be saved when the rain comes. Before that was the Most Productive Overs method, a Richie Benaud-inspired system that really didn’t make much sense.

But back in 1973, we had the average run-rate method. A horrible system that basically said if you had a 300 total in the first innings, and the second team only had 25 overs, they’d be chasing 150. You can probably already see the issue here, it doesn’t factor in wickets.

In a match that was basically a semi-final between England and New Zealand, the rain came beforehand, and it was changed to 35 overs each. The Kiwis make 105/7 from theirs. England were 34/1 after 15 overs.

But at the crease were Lynne Thomas and Heyhoe-Flint. Behind them in the order was Enid Bakewell. They were the three leading run-scorers in the tournament, and all averaged in the 80s. It is still one of the greatest top-orders any women’s team has had.

And at the 15 over mark, with the match easily within grasp, it rains for the rest of the day, and England lose by 11 runs.

That could have ruined the entire plan, which was weirdly, not to have a final, but ensure the last match was between Australia and England, with the hopes it became a default final.

Luckily for the organisers, New Zealand’s first match was washed out, and the loss to the International Women in the thriller meant the Kiwis didn’t have enough points.

The gerrymander works: England meet Australia in the last match.

The home side bats first, Thomas falls at 101; Heyhoe-Flint at 218; Bakewell completes a hundred and England surge to 279. Australia start cleanly, then lose two for one and never recover. A real princess (Anne) hands a shiny trophy to the queen of cricket.

Heyhoe-Flint made runs and won a World Cup as captain, but that was nothing. Because before that she waved her wand, borrowed a cheque book, invented a concept and manufactured a global event from nothing.

***

This tournament changed everything. The men were inspired by their counterparts and started hosting their own tournament, but gave a percentage of the profits to the pioneers. And Lord’s, embarrassed by not hosting a game, changed their membership to allow women into their beautiful pavillion. Women and men’s cricket was seen as the same, and we all lived in fields of lollipops and lemonade.

No, obviously none of that happened.

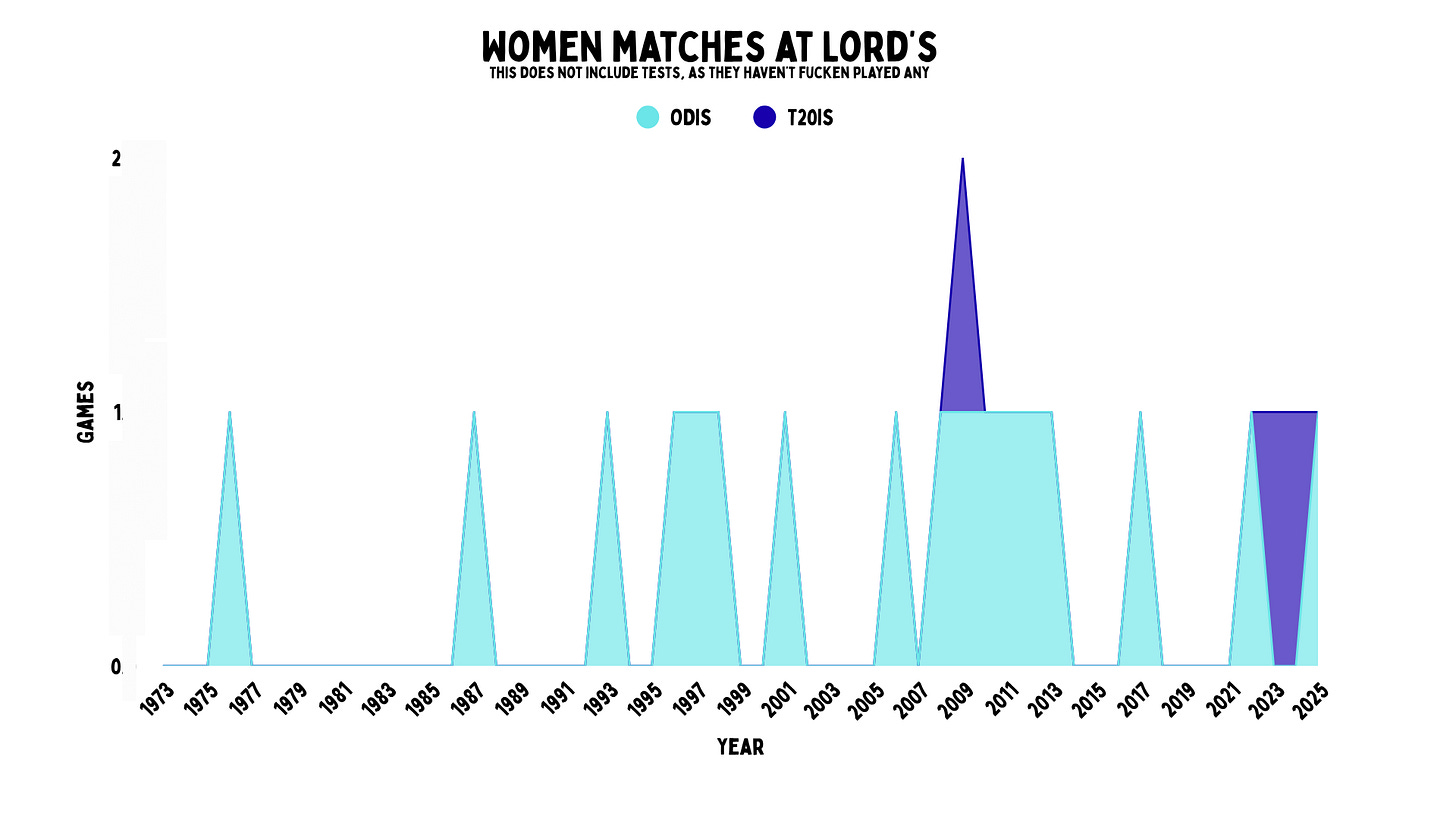

The MCC did host a Women’s ODI in 1976, and then straight after in 1987. From then on, they held them regularly, except when they’d forget them for years. Since they held the 2017 World Cup final, they’d managed to fit in two more.

In 1991, Heyhoe-Flint applied for membership of Lord’s, with famous people supporting her. The MCC voted 4727 against, and 2371 for. But in 1998, they finally allowed women to be members.

Unsurprisingly, Heyhoe-Flint was in the first induction.

Her friend, Union Jack Hayward, went on to prop up Wolverhampton Wanderers for years. But it is still remarkable the arch empire man turned cricket into a truly global game.

After years on their own, the women’s governing body was brought into the ICC in 2005. It gave organisational structure well beyond anything ever seen before in women’s cricket. But also for the first time, women were not running their game, and it was an afterthought with the ICC for many years.

But it did take the sport to a bigger platform.

By 1997, there were around 50,000 in attendance at Eden Gardens. In 2020, the MCG hosted 86,174 people at the final. And in 2017, Lord’s was sold out when England beat India.

This story isn’t just about the rise of the women’s game. It is about cricket pioneers building something. This ad-hoc collection of schoolgirls, mums, sisters and die-hard amateurs gifted the sport something it never had: a global showcase. The men hadn’t staged a multi-team tournament in more than sixty years. The women assembled one from scraps. They all got together to give us the World Cup, which they built piece by piece, inch by inch, with their own hands.

Only one side lifted the trophy, but all of them changed the game.

Great read about something we as cricket fans really ought to know more about. One quibble: Enigma was invented in Germany. It was cracked by the Polish and then routinely decoded at Bletchley.

Powerful piece. This is why you're the best writer in cricket ♥