Pakistan's Babar and Rizwan road

While the world was building freeways for their faster cars, Babar Azam and Mohammad Rizwan were jaywalking for Pakistan. Something had to give.

Buy your copy of 'The Art of Batting' here:

People don’t walk as much in America. They have drive-thru everything. And it’s almost as if walking is illegal. Well, it kind of is - it’s called jaywalking.

In the early 1900s, people rode bikes, walked, and dragged carts around with them. But there were also cars. And if you’re selling automobiles, the last thing you want is people on the road in the way.

The car industry came together with a campaign to free the streets for their machines. And that is jaywalking. At first, simply a PR exercise, and later it became a law. Get off the roads you filthy walkers, there’s something faster coming through.

Babar Azam and Mohammad Rizwan are not in Pakistan's team for this Asia Cup. Now they haven’t been for a while, but what would usually happen is when the tournament comes, the senior stars would come back in. You’re never truly dropped, just misplaced. And so there was a lot more surprise when Pakistan’s squad came out and these two weren’t in it.

But where the men in green often make their mistakes is in a lack of consequences. If their stars know there’s a chance of coming back anyway, why change? Why evolve? Why improve? The call will come.

If you follow through and there is a penalty, and you stick by it, then people sit up and change.

Babar Azam and Mohammad Rizwan have been walking through the middle of the T20 road while cars speed by them.

But when in the side, those two stop violent crashes, which is what happened to Pakistan today.

***

The singularity is the point at which artificial intelligence surpasses human intelligence. When these two bat together, it’s the anchor singularity. Where the slow batters take up so much space, almost no one else is needed.

Their style is not really the issue, it is their combination. Like a wide load truck taking up two lanes.

This is the strike rate by year of the combined top ten-ranked sides for T20Is. It gives you an idea of what the par scoring rate has been. And then we also have used Babar Azam, not just when playing for Pakistan but also his franchise T20 career. In that time, Babar has been under par compared to normal strikers four out of ten years.

In some ways this is a little bit unfair, because we know what kind of player Babar is. And despite being one of the biggest stars in the world, when it comes to T20 cricket, he’s just slow.

The best way to look at this is by his true strike rate. Four of his years we have him as a negative, and another is just holding in . He’s had five plus years as well. But overall, he bats at what we call a neutral strike rate.

But when you factor in his true average and the sheer amount of runs, this is a plus player. He is not perfect, which is why he’s not here at the moment, but Pakistan does not have a history of incredible T20 batters.

In fact, you could take it further and say they’ve never had a genuinely great T20 bat. Or even that close. The only two with a big chunk of runs are Rizwan and Babar. Only Misbah has ever averaged well over 30 before.

The tuk-tuk was called that because of the speed of his white-ball batting. He’s an outlier, and not in a good way. There are two others - one was the streets-will-remember Imran Nazir. And the other is Shahid Afridi, whose numbers still hold up, despite T20 being after his peak with the bat.

Pakistan have created two kinds of T20 batters. Absolute strike rate slappers, and tuk-tuks. And nothing in between. Fans might moan about how Babar and Rizwan play. But the biggest question is why they’ve found no one else.

It means Pakistan have created this incredible atmosphere where their two best T20 players are also the ones they complain about the most. Babar and Rizwan are saviours and scapegoats, at the same time.

While Babar steals much of the attention, Rizwan is fantastically weird. He went from a par batter in terms of true average, and then supersized it. You have to appreciate a player who really struggled to make something work, only to find a method. He went from barely a fringe player to someone who was basically impossible to dismiss.

Slowing him down is very possible though. You barely have to even ask him. He relies on the catch-up innings, getting incredibly set, then looking for boundaries late in the death.

By the impact metric, he did have a decent run when he was averaging a load, but he’s still rarely had much say in games. This year he was averaging more than 50, and we still had him as a negative on impact. He’s facing around a quarter of the deliveries per game, and yet not moving the game forward. It means the guys at the other end have to go hard.

Anchors are becoming increasingly controversial, but the basic concept remains sound. If Rizwan can stay in for that long, Pakistan are always going to have wickets in hand.

The issue for them is that Babar plays similarly. In fact, almost identical, like his and hers cars. Two guys filling the same role, in the same position, at the same time.

Their anchor singularity means they face so many balls that no one else can actually come in to score fast. They’re taking up almost the entire road, there is no room for anyone else. Pakistan selectors originally suggested that the best batters should face the most balls. But that idea has been out of date for a long time in T20.

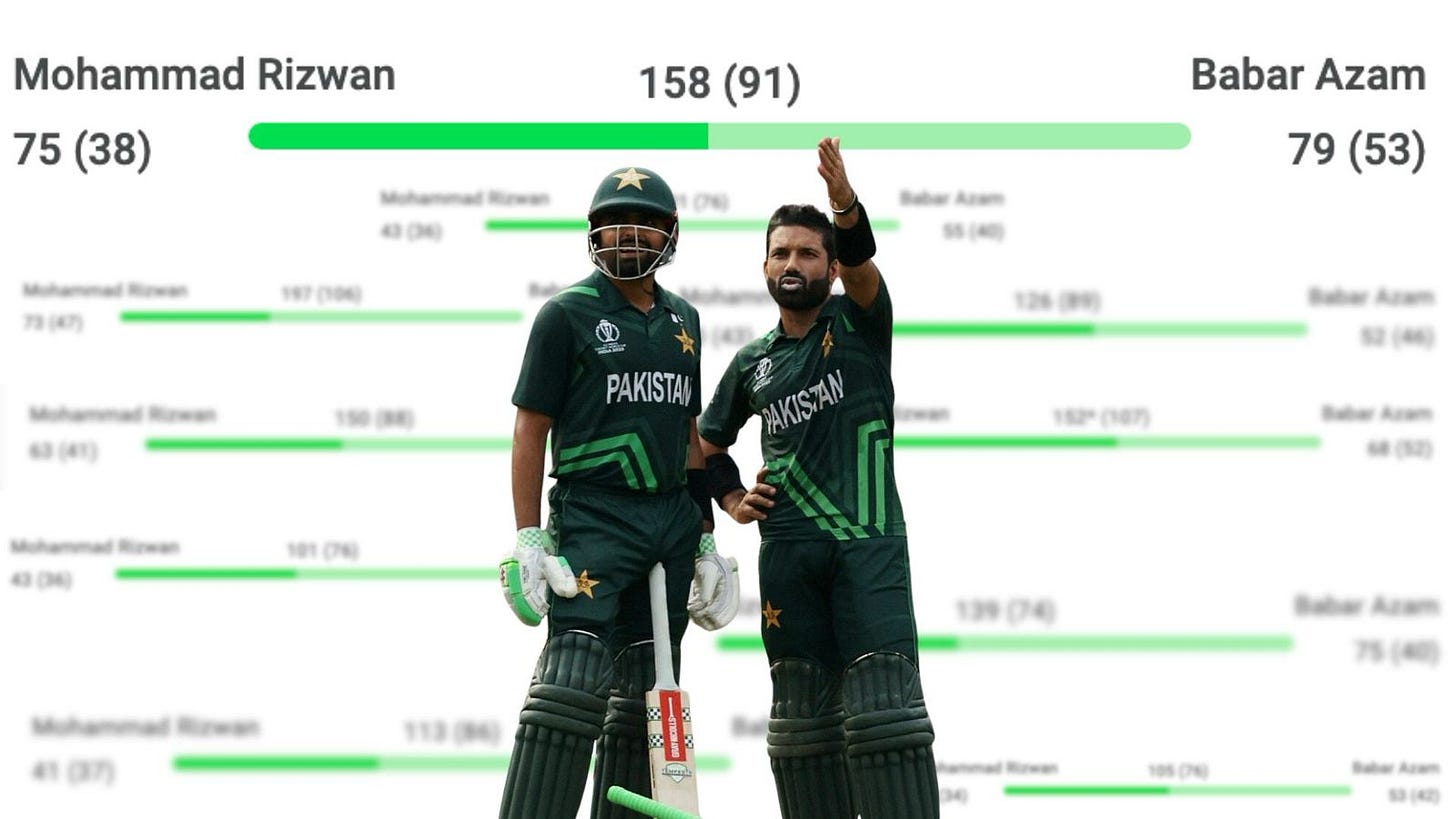

However, these guys have faced an incredible amount of deliveries. Only two pairs in T20Is have scored more than 2000 runs. Ireland’s top-order duo of Andy Balbirnie and Paul Stirling have 2184, but Babar and Rizwan are more than 1000 runs ahead of them.

That is a remarkable effort that should be shouted from rooftops.

In ten games, they made more than 100 runs in a partnership, and Pakistan won every one of them. So when the two of them don’t go out, it works.

Perhaps the most fun version was when England made 199, and Pakistan chased it down without losing a wicket. That’s the dream: two guys you can’t get out, who can still score.

And so despite all those duets, they’re not scoring at eight runs an over. They average a stupid amount of runs, but without much boom.

So there is a dichotomy with them: if they pass 100, they win games. The nightmare is where they meet, chew up balls, and then go out. And that is the problem with an anchor. But this is a double anchor. Nothing stops the ship from drifting more into trouble than them, but also stops them from finding any speed.

An anchor on their own is an issue. Two anchors is a problem. And when neither kicks on, it's a nightmare.