Pakistan’s Pune Paradox

Preparing extreme pitches isn’t always a bad idea, but history shows it might not always be a good one either

When I arrived in Pune in 2017, the messages started straight away. The Australian setup was trying to get the call out to all the press: look at the wicket; it’s gonna rag. How could we ever possibly win this match?

A few days later, we had lived through Matt Renshaw almost shitting himself on the field and Australia somehow beating India.

At that stage, it was the first loss for India at home in almost five years. Although Australia had prepared well for that tour and had a Steve Smith wonder knock, no one really thought there was a chance of an upset – especially with the Indian spinners, who usually took control of such conditions.

But India’s problem in that match was that they made a wicket that spun so far, it turned even lesser spinners deadly. In that match, the leading bowler wasn’t Ravi Jadeja, R Ashwin, or even Nathan Lyon – it was Steve O’Keefe.

India made a wicket so extreme that, instead of giving them an advantage, it turned the match into a shootout. And they got shot.

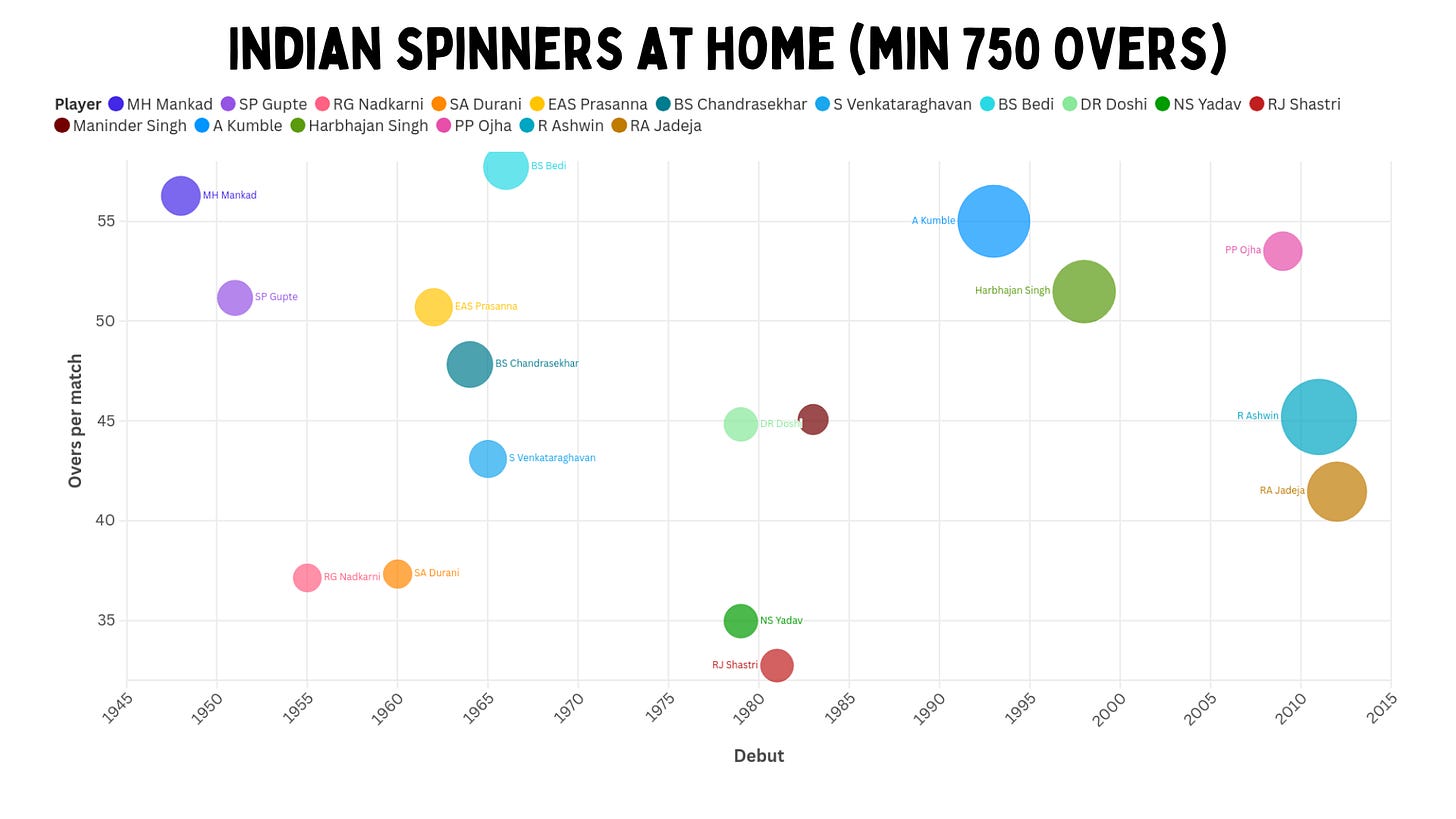

We know that India won a lot of Tests, most of them pretty easily. So this idea of having raging turners was also good for their spinners, not just in the obvious ways. Indian spinners in the old days bowled so many overs. Bishan Singh Bedi bowled almost 60 overs a match at home. Vinoo Mankad and Anil Kumble are at just over 55 a match, with Pragyan Ojha and Harbhajan Singh just under that mark. Ashwin is ten overs a match below that, and Jadeja barely bowls more than 40.

So it worked, right? They got more overs overall out of their greatest spin pairing and still won a bunch of matches.

But at times, Tom Hartley, Mitch Santner, and Steve O’Keefe would outbowl the world’s two best spinners. Was it worth it? They won 18 consecutive Test series. Even with the occasional embarrassment of an Ajaz Patel moment, it worked really well.

But India did it from a position of strength. They not only had two great spinners, but both could bat – and a lineup filled with players who played the turning ball brilliantly (at least until the pitches ruined that too).

Pakistan’s plan came from a string of embarrassing losses and boring draws. Losing to Bangladesh meant they had struggled on flat wickets and lost on seaming ones. And the loss in the first Test against England was perhaps the most brutal – scoring 500 in the first innings and still losing their trousers.

So they decided that spin – savage spin – was the way to go. When you’ve tried everything else, you might as well.

They went all in on a reused wicket. There’s a subtle way to do it, but Pakistan took a blowtorch to pitch curation. They used a potential 14-day pitch – although the plan was never to let it go that far. And it worked. They turned around a series from 0-1 to 2-1. That’s a remarkable comeback.

And they won the first Test against the West Indies as well. This meant that, since going all-in on spin, they had won three straight Tests. That was the plan, right? After losing so many games and looking toothless, they had found some venom.

It also gave us two extraordinary heroes. Sajid Khan and Noman Ali are like two men who work in adjacent work cubicles of lower middle management – the fun one with jazzy socks and bow ties, with the other guy who works diligently while solving Samurai Sudoku on the side.

Obviously, Sajid Khan and Noman Ali are not Ashwin and Jadeja. But they’re also not Jack Leach or Shoaib Bashir. So going up against England with this idea (especially with batters to back it up) made some sense.

The West Indies were more interesting. On paper, they had two spinners who could be very effective on turning wickets and some backup options if needed. However, their batting was poor.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Good Areas to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.