Rohit Sharma retires from Tests

He was not one of the greatest Test batters of all time, but he played innings that even some of the best ever could not have.

We are offering a 30% off deal for The Art of Batting. Just click this link and use the code GOODAREAS30 at checkout. This works for orders and pre-orders. It’s a global discount, so it will work across Australia, Canada, India, UK and US sites.

Nohit Sharma. That is not what you want to be referred to when a short time before Viv Richards has said you could be one of the best batters in the world. And you aren’t. At least, you’re stunted. Kind of lost down the order, not sure of what to do.

It wasn’t that Rohit was bad; he started with two hundreds, but he did bat at times as if he was confused as to what his purpose was. A player cut adrift from motivation or role definition. Maybe he simply wasn’t necessary, and so he was like your fourth nicest suit. Sitting in the closet, on the rare days you get that far into your rotation.

And then, late in his career, he was asked to open. It’s never a good sign that you’re an important part of the batting line-up. The middle-order player thrust upwards is really more of a hope, an experiment. It’s like where you sit your least favourite uncle at a wedding. If it works, great; if it doesn’t, you’re out of the family.

Instead, Rohit Sharma became a late-stage opener and made it work. And now, he was setting the scene.

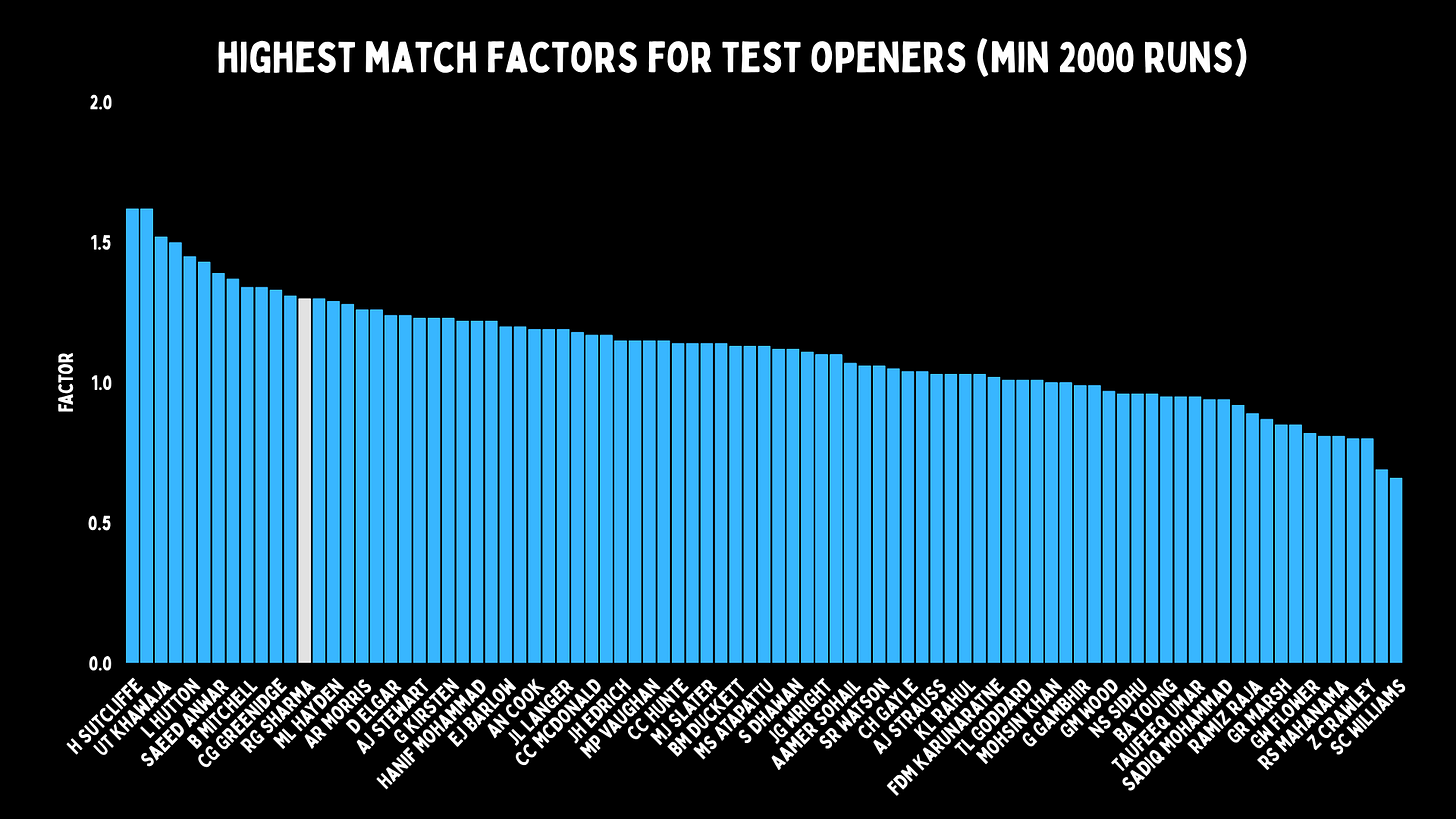

So here is my favourite stat on him. In Tests where the average was more than 30, Rohit was actually 10% worse compared to the rest of the top order. In Tests where the average was low, the ball or wicket was doing something, he was absolutely freaking magnificent.

Rohit Sharma needed something to inspire him, and the harder the wicket, the more he scored.

Numbers are great, but Rohit Sharma had something else – this almost rubber-like way of hitting the ball. He never muscled it, he didn’t punch it, and even when slogging it wasn’t with violence. He had one of those beautifully rubber bats, where he always seemed to be tapping the ball, but it would disappear as if shot out of a cannon.

He would shuffle into line, clip a straight drive, and the ball would travel faster than physics suggested it should have.

He was a big man with a feather touch. He looked like he could have been a bruiser, but batted as if he had a poet’s soul: short, minimalism with a pretty flourish. He was part of every moment, yet detached from it. As if at once playing a flick off his pads for six, while also sipping chai with his friends and laughing at the ease at which he did it.

It all looked so easy, until the magic ball arrived.

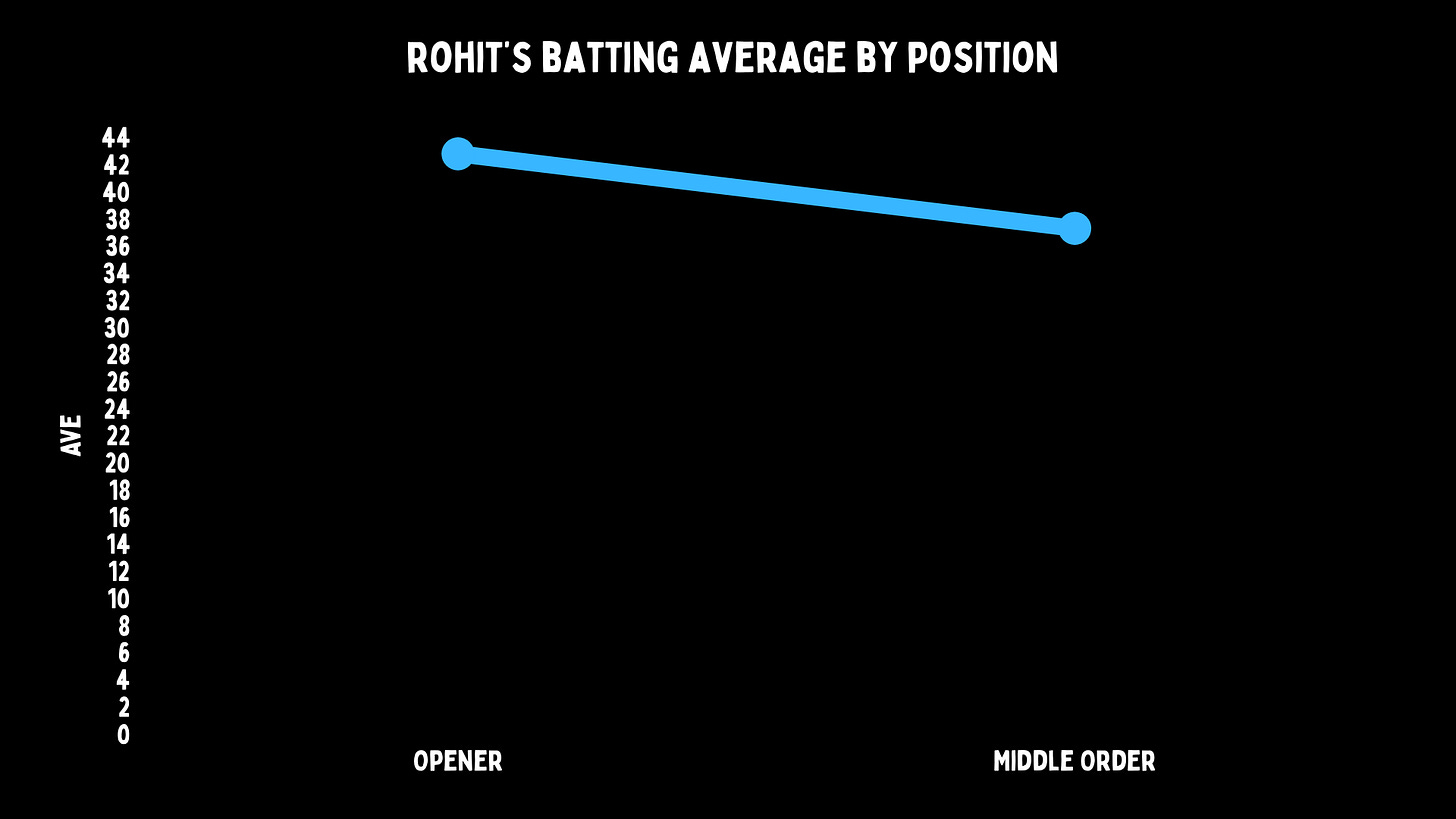

Rohit as an opener, averaged more than batting down the order. And that is extraordinary, because he wasn’t just a middle-order guy going up a spot. Rohit batted at six. That is the cruisiest Test batting spot. That is where kids used to start and old fellas would end up. It is where you put your fifth bowling option if he’s ok with the bat.

Opening is way tougher, it is the hardest spot. When writing The Art of Batting, we had to factor in that openers make fewer runs than anyone else. There is a tax on batting at the top of the order, and Rohit did not pay it.

And remember that Rohit played 14 Tests in 2024 as an opener. That is the most matches he played in a year by a distance. During this period, he would appear to be washed, and yet still his average is way better opening.

There was a bit of a pattern of players opening the batting after doing really well in ODI cricket. So let’s talk about his fellow double-centurion opening brother, Martin Guptill. Both of them ended up top for their nations in white ball and then the red one. In Guptill’s case, it just never worked. Ever. Not even close. All that talent, but the red ball tormented him.

The biggest challenge for opening the batting is the lateral moving ball. So you would have to look at him opening by country, as Guptill certainly faced swing and seam a lot.

There are no straight lines for Rohit; look at his match factor for each location. He was horrendous in Australia and South Africa, but magnificent on Indian wickets and in the UK. Try straightening that out.

But being good in England, and not just decent, but outstanding, is really some effort against the new ball.

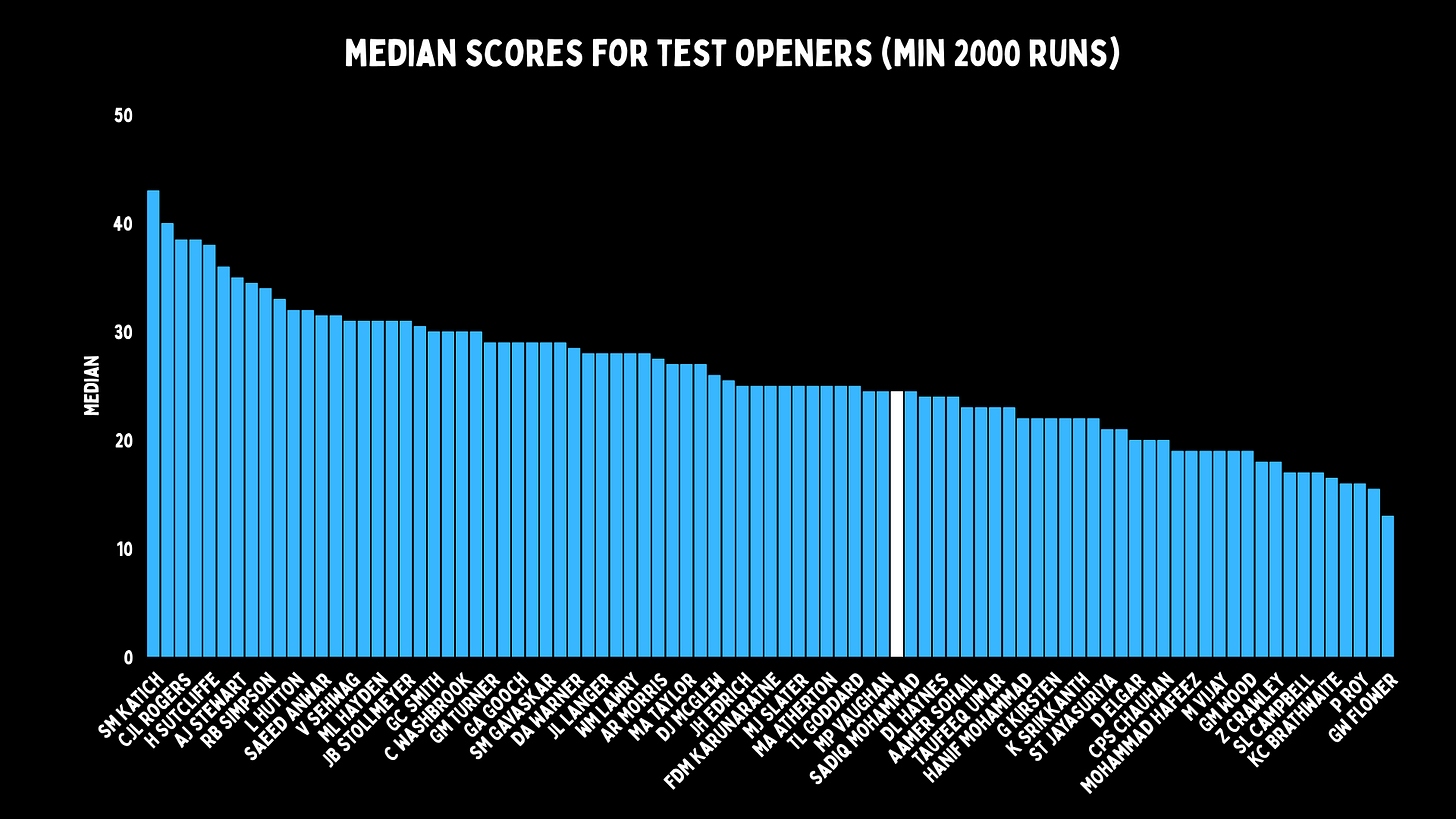

He wasn’t a consistent opener. West Australians Chris Rogers and Simon Katich would walk out to bat and come back with a score almost every time. They have high median scores. Rohit is down the other end, making more hundreds than 50s as an opener.

He was all or nothing, so his variation of scores is really high. But that also suits the kind of player he was. You didn’t want Rohit to open like Chris Rogers; you want the power, threat and intent. Because if he made a hundred, you would feel it. No one wanted to bowl to him. So his runs hit harder. And the greatest sides of all time usually have that kind of opener.

The one that keeps the opposition captain up at night.

Rohit made hundreds a lot. He made them more than 50s. Only two other openers converted more often than he did. He was either out early, or making a hundred. It’s not conventional, but it was brutal to go up against.

He is not one of the greatest openers of all time, but average is probably an unfair way to look at him, as for most of his career he batted on really tricky wickets home and away. So we have him as 30% better than the players in his games. Chris Rogers has a higher average, but Rohit was better.

But even adjusting for that, we are not looking at a huge impact overall. Just on occasion.

And when you make less than 3000 runs opening, and your last year of Test cricket is 14 matches while your form is so bad that you have to drop yourself, that is going to tank your overall numbers.

Recently, I did a video where I called him one of the greatest all-format batters ever. That angered people. It seemed like a pretty obvious statement. Perhaps ODI is the only format he was great on his own, but the collective of all three is massive. Yet, despite having won a T20 World Cup, Champions Trophy, a bunch of IPLs and leading a pretty fantastic Test side, Rohit isn’t as universally adored as he should be. And the online battles between his fans and Virat's make everything toxic.

But Rohit was a fantastic player when it mattered, if not all the time.

Like when India decided to turn their pitches into the hardest to bat on of any ever concocted by man, Rohit stood up. There were some times when he looked like the only batter who could. The home wickets tanked the numbers of Virat Kohli and Ajinkya Rahane, but it seemed to give Rohit a purpose.

That thing he had been looking for. Opening started his new phase, but having to survive wickets like that brought out the very best in a batter whose peaks were obscenely high.

So, let’s go back to where we started. Rohit needed the mission to be his best. At home, on wickets where the top six averaged more than 30, he was 25% better than normal. He was fine on flat wickets, but nothing spectacular.

When India put out a pitch that absolutely no one could make runs on, he was 120% better than the top order batters in those matches. Some numbers stop you, and you have to have a moment to yourself. This is one of those.

Strangely, this smooth looking number six batter needed the worst wickets in cricket and opening the batting to unlock the very best of him.

You didn’t need to see these stats; you felt them. Rohit would open up on a wicket that had turn and bounce, and he’d be batting like none of it mattered. All while the poor guys at the other end were trying to handle invisible trampolines and 90-degree turn.

Rohit Sharma was not one of the greatest Test batters of all time. But he could play innings that even some of the best to ever to do it simply could not.

Nohit Sharma. That is not what you want to be referred to when you can be the Hit Man. A bruising figure with a velvet touch. A man who could, with a shrug of his large shoulders, decide to become an opener late in his career and only came to life when the wicket was almost impossible.

If he was an actual hit-man, he would have been the type who pretended to be a delivery driver or a lost dad in a lobby, before perfectly pulling off his very dangerous assignment.

It is perhaps most ironic that the man called Nohit was, at times, the only one who could hit.