The joy of Jofra and Jasprit

You need to celebrate every ball of theirs; athleticism is a slow-melting ice cube.

You can buy my new book 'The Art of Batting' here:

Jofra Archer is running in, wearing whites.

For a moment, that is a great enough feel-good story. After injuries, surgeries, and short spells in white-ball cricket, just seeing him at the most famous end in cricket - running in the same direction where he knocked Steve Smith out - is enough. It’s joy.

It felt like maybe we would never see this again. And if he did bowl, it wouldn’t be the same anyway. He was beyond his period of supernatural elasticity and youthful athleticism after his injuries, like what happened to Jeff Thomson after ruining his shoulder. Thommo’s career didn’t end - his reputation and talent kept him around - but he wasn’t the same after. More like an actor playing Thommo in a film, with a wig on.

Archer also can’t be the same. Being a fast bowler means being hurt every single day of your life. You bowl through scar tissue, without toenails, and despite micro-fractures in your spine that haven’t yet been picked up.

Pure fast bowling, like Lord’s in 2019, doesn’t last forever. Sometimes it bends towards medium-fast. Occasionally, it breaks entirely.

The previous delivery Jofra Archer bowled in Test cricket was 82 mph, on day one of the Ahmedabad Test in 2021. Strictly fast-medium.

This one at Lord’s - a loosener - was 87.4. Not fast, but hinting.

Archer could still bowl, and he could bowl fast, but could he bowl Test-match fast? Not for 24 balls spread over two hours of strategic timeouts - but spell after spell, day after day, time after time.

Or, to be clearer, could he turn back time? Back to when Jofra Archer running in brought joy to everyone who wasn’t facing him.

Jasprit Bumrah is such a big force on a cricket match that he seems to warp them, whether he is bowling or not. At times in Australia, it was like not having the ball was sucking the energy out of his team. India were one side when he was at the crease and another without him.

In sport, there is something called Ewing Theory. It is named after the Jamaican centre for the New York Knicks, Patrick Ewing.

It was coined by sportswriter Bill Simmons to explain the paradox of how some teams get better when they lose their best player. The Knicks thrived suspiciously well without him, suggesting that the gravitational pull of a superstar can sometimes warp the team around them. Strip away the safety net, and suddenly the supporting cast plays freer, the ball moves cleaner, and the system breathes again. It’s less about talent and more about liberation - like cutting the lead singer and discovering the drummer can actually sing, and write better songs.

It’s a little misleading to say India lose more when Jasprit Bumrah doesn’t play than when he does. That involves where they’ve played, and a stunning number of collapses. But even within a game, India is a different team when he has the ball.

It’s not quite like when Richard Hadlee was bowling at one end and Graham Gooch said the other end was Ilford Second XI. But there is an aura gap. When Jasprit Bumrah gets on a roll, it feels like he could take a wicket every single ball. And at the other end at Lord’s, Mohammed Siraj and Akash Deep - both awesome at Edgbaston - are in perpetual exasperation.

Bumrah isn’t really like Ewing. If there were a centre from the NBA he’s more like, it would be the Denver Nuggets’ Nikola Jokić. A player unlike any before him, with the passing and vision of a point guard, in a nearly seven-foot Serbian spruce-type body. The Nuggets have the best player in the world, and when he’s on the court, they are great. The minute he hits the bench, they become the worst. Their players get sucked into a black hole, unable to play normal basketball again.

But sometimes Jokić doesn’t play. And in those games, the Nuggets often steal a win. Their players know how to do regular basketball, but it only works when they haven’t been playing Jokić ball.

There is no bowler in the history of the game like Bumrah. Siraj and Akash are clearly international-quality seamers, but they are normal. And when they’re at the other end, they must feel supplementary. The combined third nipple of Indian cricket.

When Bumrah doesn’t play, they return to regular form: quality international seamers.

Jasprit Bumrah is so good at cricket that he almost appears to bend everything around him. But when he is hurt - or when India are worried about him getting that way - they become a different side in his absence.

Both Bumrah and Archer have actions that really shouldn’t allow them to bowl very much. They are both scary fast - which is already a problem - but they also force their bodies into incredible stress at the moment of release.

Their injuries are different. Archer’s is mostly the elbow. His hyperextension gives him his pace, but also means the force through that part of his body can’t sustain it. Bumrah also has hyperextension of his elbow, but hasn’t had the injuries that follow. He gets stress fractures in his back (something Archer has had, but less often). When either bowler stretches or grabs at something, it makes everyone nervous.

It’s another reason you need to celebrate every ball; athleticism is a slow-melting ice cube.

So when you see Archer at mid-off folding his back, you wince. When he takes the tape off his arm, you hope KL Rahul has asked - and not that something is wrong. When he stretches on the boundary, you tell yourself this is all normal. Because you know how fragile this is. They are one slipped disc away from medium pace.

You frantically check the speeds of Archer’s deliveries, just to be sure. His first spell, the average speed was 90. That is fire. The second: 86. That’s more of a worry. But in the third, he’s back to 87. So it’s okay again.

Every fast rising ball that Karun Nair drops his hands on, or bouncer that Rahul sways from, is a victory.

For Bumrah, every wicket is. Perhaps no bowler in the history of our game has been more expected to take a wicket - no matter the ball, pitch, or batter - than him. Some of that is the weight of expectation from a country of a billion people. But it’s also his skill. When he’s on song, it feels like every ball is going to break through.

Unlike Thanos, Bumrah is actually inevitable.

Yet, he is a defensive bowler first. The wicket was tricky, and England decided to go slow. Even within that, England scored at more than 3.7 runs an over against the other three seamers. Akash was up at fours. But against Bumrah, they went at 2.7. He was the biggest wicket-taking threat, and the best defender.

A shape-shifting samurai with a nuclear sword he uses as a scalpel.

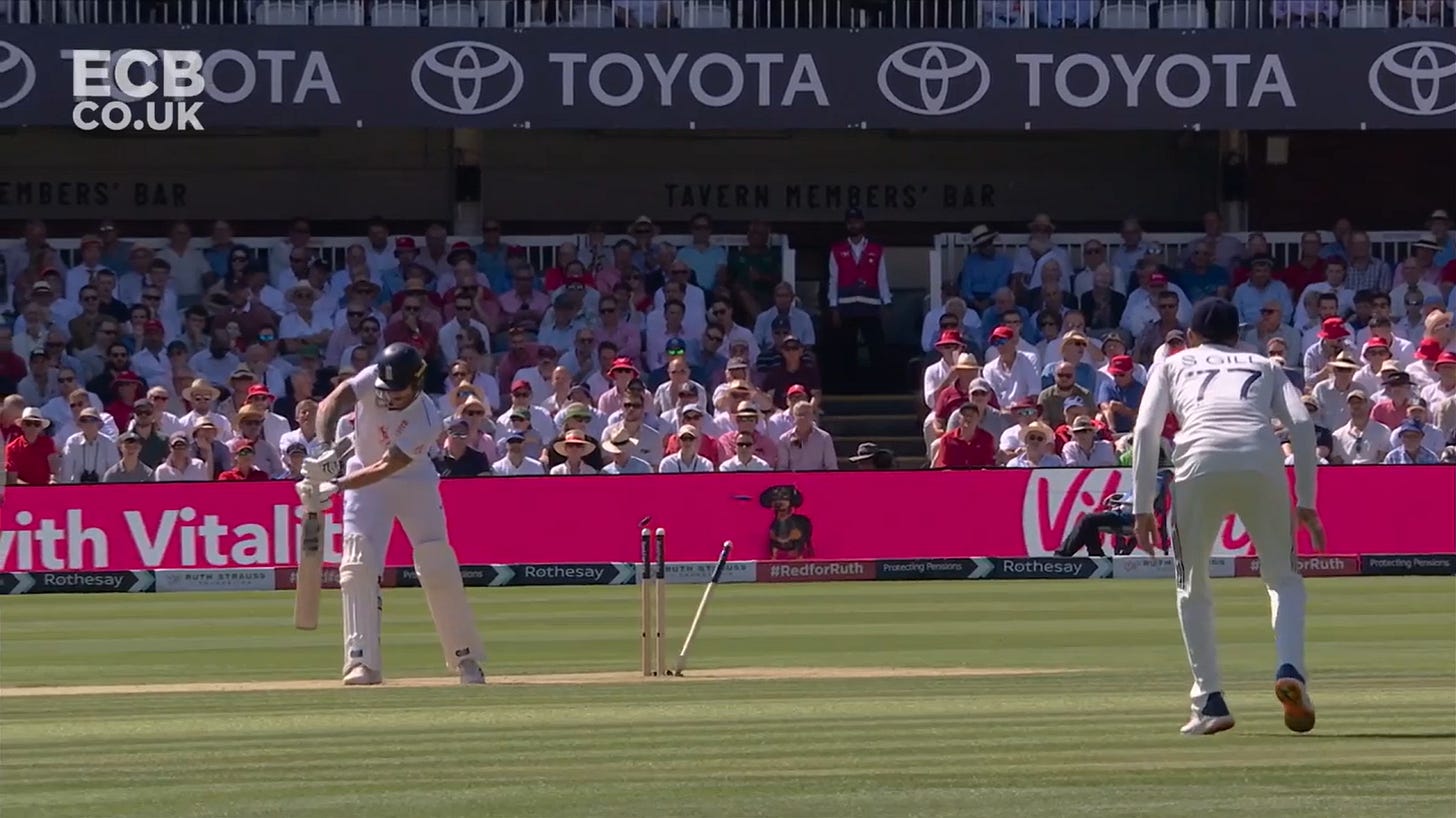

England’s middle order is their machine, and Bumrah has bowled Brook, Root and Stokes. Bowled them. Didn’t nick them off, or slip one onto their pads. Broke their stumps - of the two best batters, and the captain. On a flattish wicket, with little support from his two lieutenants.

It was exciting and fun. It brought joy.

But nothing like Jofra Archer did.

Before he even had the ball, the crowd could see him heading for the crease - and they were energised. The roar for him coming in to deliver two looseners - at 87.4 and 85.8 mph - was already incredible.

Then, the third ball.

Going up against the best young batting talent in generations, Archer sprinted in with giant golden chains bouncing around from chin to chest, a white sleeve over his problematic elbow, and released the ball on a length near leg stump.

The seam was perfect. And when it hit the string, it nipped away from Jaiswal - whose wonderful hands couldn’t help but chase - and he edged to Brook at slip.

Archer didn’t run to the catcher. He sprinted the other way, screaming into the air, letting out four years of pain, worry, physio appointments, surgeons, insurance claims, and heartbreak - in one moment, to the North London air.

He could have run forever, if not for slamming into Shoaib Bashir’s chest.

You’d be forgiven for thinking the two are best friends, such is the beeline Archer made for him. But the spinner was in high school when Jofra’s last Test ball was delivered. None of that matters. Because Archer didn’t know if he would ever do this again: steam in from the Pavilion End and take out one of the best batters in the game.

Joy. Fast bowling brings broken bones and wickets. It hurts. It embarrasses. It leaves a mark. But at its very best, it brings joy. We are used to the joy of Jasprit Bumrah, it comes so often, and like today, in bundles.

The England bowler’s well had dried up, perhaps never to be used again. But today, Jofra Archer just running in, wearing whites, brings joy.

His wicket, brought more.