The miraculous Ollie Pope

Maybe this weirdness is our future. A weak-chinned chimaera patrolling cricket’s run barren landscape feasting on scraps.

Buy your copy of 'The Art of Batting' here:

I can’t see the future; I have no ability to look into events that haven’t yet happened. Like all humans.

But as I watch Akash Deep coming in to Ollie Pope, I know what is about to happen. In fact, let me take it a step further: I can see it. The score is 80/3, but I know it will be 80/4, and that Ollie Pope will be bowled.

I don’t tell anyone, because it would be weird. But as Akash comes in, it’s clear to me it’s going to happen. The ball is pitched on a length, just outside off; it darts back in towards the stumps but also bounces. It is not a normal delivery that would bowl someone, but then it hits Pope’s elbow and goes straight down onto the stumps.

I tell everyone around me that I saw this coming, and no one even looks in my direction. I can see the future - it’s a miracle. And still, no one cares.

But then, I think about it. Assuming Pope will be out soon when he’s batting in the fourth innings is a pretty safe assumption. Thinking that he might be bowled is perhaps just as likely.

I didn’t have a premonition; I’ve just watched a lot of cricket. And specifically, heaps of Ollie Pope. That alone can warp a brain.

His career is a miracle, and I mean that almost literally. It's a miracle that he’s still here, his continued existence is almost supernatural.

There has never been another batter like Ollie Pope, it’s miraculous.

***

The Parks is a cricket ground, and on the 28th of March in 2017, there was a first-class match played between Oxford University Cricket Club and Surrey. The county side had eight international players in their lineup. Oxford had students. It’s an odd match, but coming in at number six in that game was Sam Curran, who would go on to be the ninth player in this team to represent England. At number seven was Pope; he’d be the tenth.

The team was clearly very strong, but he was still batting at number seven while being dismissed by a Zimbabwean whose only notable achievement in top-level cricket was a hundred in the Under-19 World Cup.

And yet, 499 days later, Pope would be batting at number four for England against an Indian attack of Mohammed Shami, Ishant Sharma, Kuldeep Yadav and R. Ashwin. It was quite the leap in a short period of time.

Oh, and it was his first time ever batting as high as four in any first-class cricket, including a game the previous month when he made his debut for the England Lions against India A at five.

If they were planning, or even thinking of him batting higher for the Test team, surely Nick Gubbins or Dawid Malan could have moved.

If England truly thought Pope was a special player, and one for the future, when they played him in the Test, surely they’d at least bat him at five. But the absurdity of this lineup shows you that Ben Stokes wasn’t there, it was in the peak of Jos Buttler as a specialist batter, and then they had Woakes at number seven.

So the only person who could have been moved to four was either Joe Root at three, or Jonny Bairstow at five, but who was also keeping.

To completely misquote Rob Gordon:

“It would be nice to think that since Pope was thrown in at four, times have changed. England have become more sophisticated, less cruel, and instincts more developed. But there seems to be an element of that first Test in everything that's happened to Pope since.”

After his early successes at five and six, Pope’s form dipped, so they binned him. Only to bring him back as a number three.

You can’t handle the easy spot, what about the toughest?

Just when he was getting used to that, they decided to make him the keeper in New Zealand and slot him at number six, despite every other living mammal in England being able to take the gloves as well.

In the middle of all that, while he was still struggling for form, they made him vice-captain. This meant that when his leader was injured (considering it was Stokes, there was always a big chance), he had to take over. So he was backup captain, understudy keeper, and an experimental number three - and that is all under Bazball.

To an outsider, Pope seems like a Test number five or six, who could perhaps move up the order later in his career. To England, he’s not a player - he’s a plug.

***

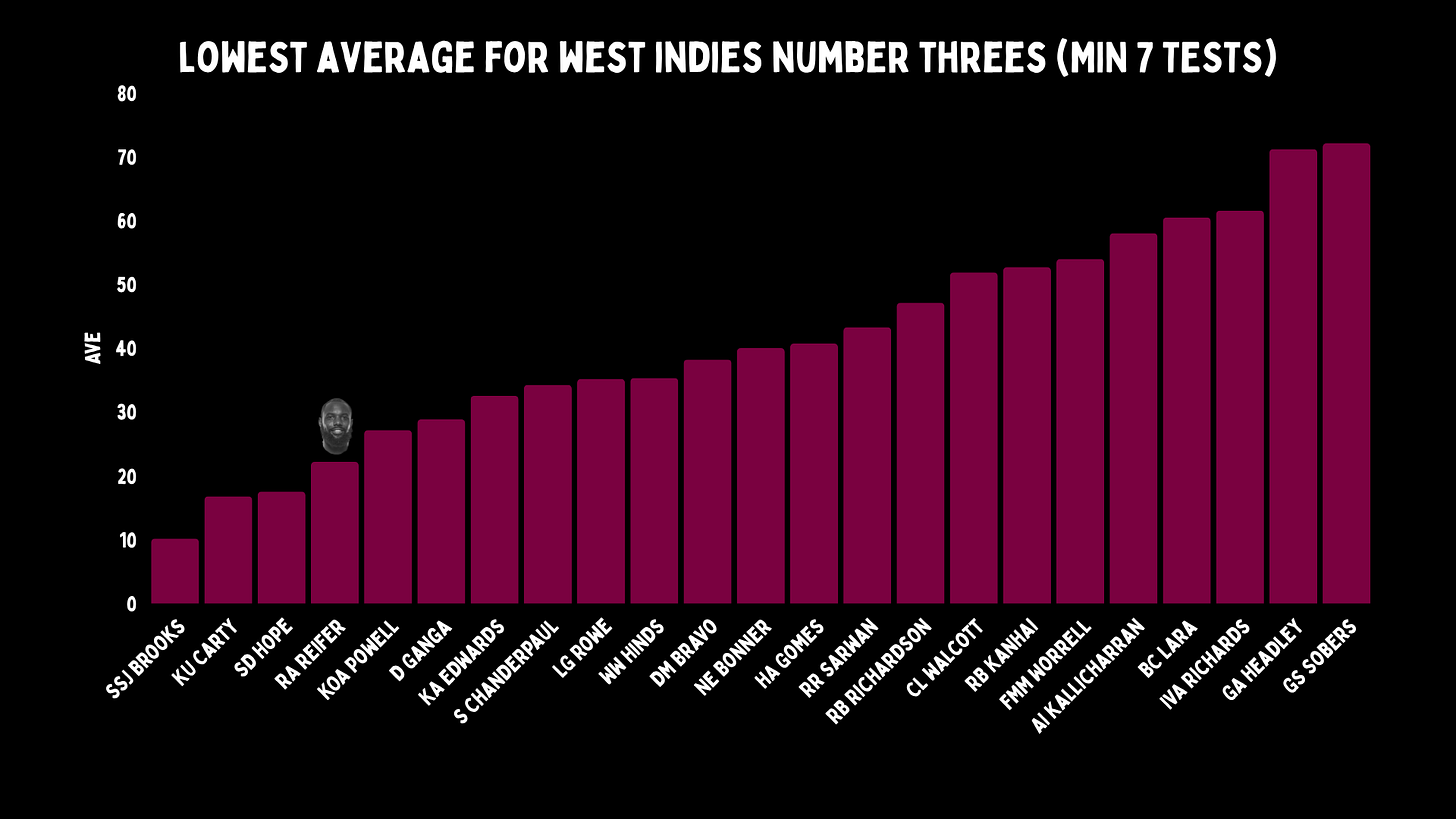

Raymon Reifer was a 31-year-old allrounder who was averaging 28 in first-class cricket when the West Indies picked him to bat at number three. Seven times, they looked at their team and said that for this match, Reifer would come in at first drop.

The West Indies have used George Headley, Garfield Sobers, Rohan Kanhai, Clyde Walcott, Viv Richards and Brian Lara at number three. All of them are in my 50 greatest Test batters ever. Raymon Reifer is not.

CricViz’s Ben Jones once suggested that Chris Woakes could go in at three for England. His theory was that England couldn’t find a top-order player, and at least they knew he could bat. He was averaging around 30 at that point. It was revolutionary, and apparently ahead of its time as teams are now going with it.

There are four kinds of first drops in Tests right now:

Ollie Pope is one of the batters who is clearly good enough to be in his nation’s top six, but the issue is he’s probably a number five. But England have had Bairstow, Stokes and Brook available to them. They have fives coming out their arse, so much so that some of them are at six as well.

So he ended up at three. And he has more than 2000 runs there - not bad for a makeshift player they nearly binned recently. England are keen to pump him up - Ben Stokes even pointed out he averaged more than 40 at three.

And he does, also at a strike rate of 80. That is a record that anyone would happily steal in this era.

He also has the ninth-most runs for England already in this spot. Now, some of that is because they don’t have a great line of people at first drop. And his average is lower than most.

But it is worth looking at his match factor as well. The first four players on this list are legit England greats. The first two are top 20 batters of all time candidates, we toyed with David Gower in our list of 50 for The Art of Batting, and Ted Dexter was a very high-quality player. Jonathan Trott was a big force for a short period of time. Root has only done it a little when everything else is shit for England.

The real comp here is Nasser Hussain. England’s former captain never met a ball he didn’t want to squeak down to third. Hussain batted like a beaver trying to rebuild a dam on the edge of Niagara Falls. He would never win, but that never seemed to bother him as he would fight so hard for every ball.

Ollie Pope is not like Nasser Hussain; he’s far prettier aesthetically, and appears like he could play any shot. And even when he’s struggling at the crease, it doesn’t feel like he’s the last guy in the foxhole who is out of bullets like Hussain was.

So in our minds, Nasser was a battler who made good through sheer will, and Pope is an ethereal waif, pissing his talent up against the wall.

Yet, not only is Pope a makeshift number three, he’s doing it with one of the lowest-scoring players in Test history ahead of him. Zak Crawley doesn’t make many runs, and also does that very quickly. Meaning that Pope is often at the crease in the first seven overs. In those, he struggles.

But if England had a stronger opening duo, or Crawley was even a Rory Burns or Dom Sibley-style player, then Pope would be a better number three.

It is hard to be a false three, and it's even tougher when you’re behind an opener with one of the worst records ever in Tests. On the days when Crawley is out playing a loose drive, it’s more Ollie Hope than Ollie Pope.

You can argue the average or effectiveness. But Pope has made the most runs at number three in Tests in the last few years, and it’s been so tough that Marnus Labuschagne - the player with the third-most runs - has been dropped.

In an era where no one’s doing well at first drop, he’s hanging in. He might be a false three, but these are real runs.

***

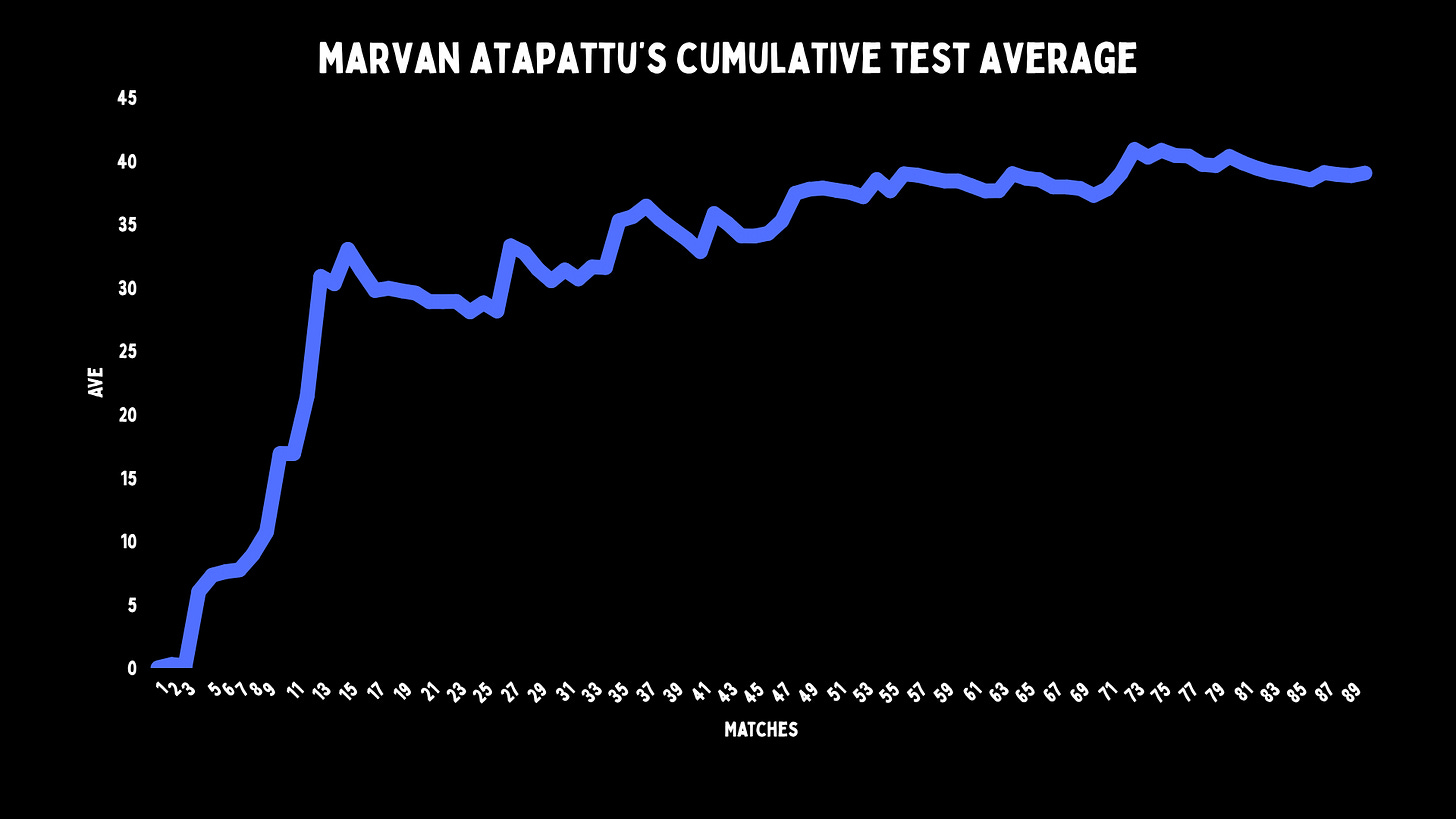

Marvan Atapattu had one of the worst career starts in the history of our sport. He played a Test in 1990 for Sri Lanka and made a pair. He was dropped for two years, came back in 1992, and made one run. His third Test was in 1994, and he made another pair. One run in six innings.

Unsurprisingly, his fourth match was in 1997. This time, he stuck around. However, after nine matches, his top score was 29, and he was averaging ten. From there, he had a respectable career, playing until 2007 and finishing with an average just under 40. At one stage, he got it above that. Considering he forfeited his early career, it was one of the best career comebacks ever.

He was an Asian opener who averaged more in England, West Indies and Australia than he did at home, and just slightly less than that in New Zealand. This was one of the weirdest careers ever. And one way to tell this was through his median score of 16.5.

Median is not something we talk about a lot in cricket; it’s average’s forgotten little cousin. It is obviously not as illustrative as average, but it does tell you things. For batters, the median is the score that lies exactly in the middle of all their innings when sorted from lowest to highest - so half the scores are higher and half are lower. 16.5 is very low. The average median score for a top six Test batter is 26.2. The median median is 26.5.

Despite averaging nearly 40, Marvan either made runs by the sackful, or none. He was rarely a player who chipped in.

We mention this because Pope has the exact same median score. 16.5.

Zimbabwean opener Grant Flower has the lowest on record - 15. So Pope is not far off him. But Flower was a slow-moving opener who fought for every ball, but was a terrible starter, and more than once batted for 100 balls without crossing 20.

His magnum opus was when Zimbabwe were chasing 99 against the West Indies, and he anchored - and we mean that as literally as you can - the chase. Flower was the fifth batter out, in the 38th over. He made 26 off 126 balls.

He flattened the stumps with his bat when he was out. No one else passed six. Zimbabwe, unsurprisingly, lost that match.

Players with low medians are weird. For Pope, the player worth looking at is Dennis Amiss - an English opener from the 1960s and 1970s.

He ended with a very good average, but his record is a mess. Against Australia, he averaged 15. Versus everyone else, it was practically 50. One reason he struggled against the Aussies were their fast bowlers (though confusingly, he made a huge score against an even faster West Indies attack), so he ended up being the first player to try a modern cricket helmet.

But he also managed to score as many hundreds as 50s. 11 centuries in total, eight of them were more than 150. He batted 88 times in Tests, 42 of them were single or triple figure scores.

Like Pope, Amiss was an obviously gifted player when he was in, albeit with some massive weaknesses like a complete inability to start an innings.

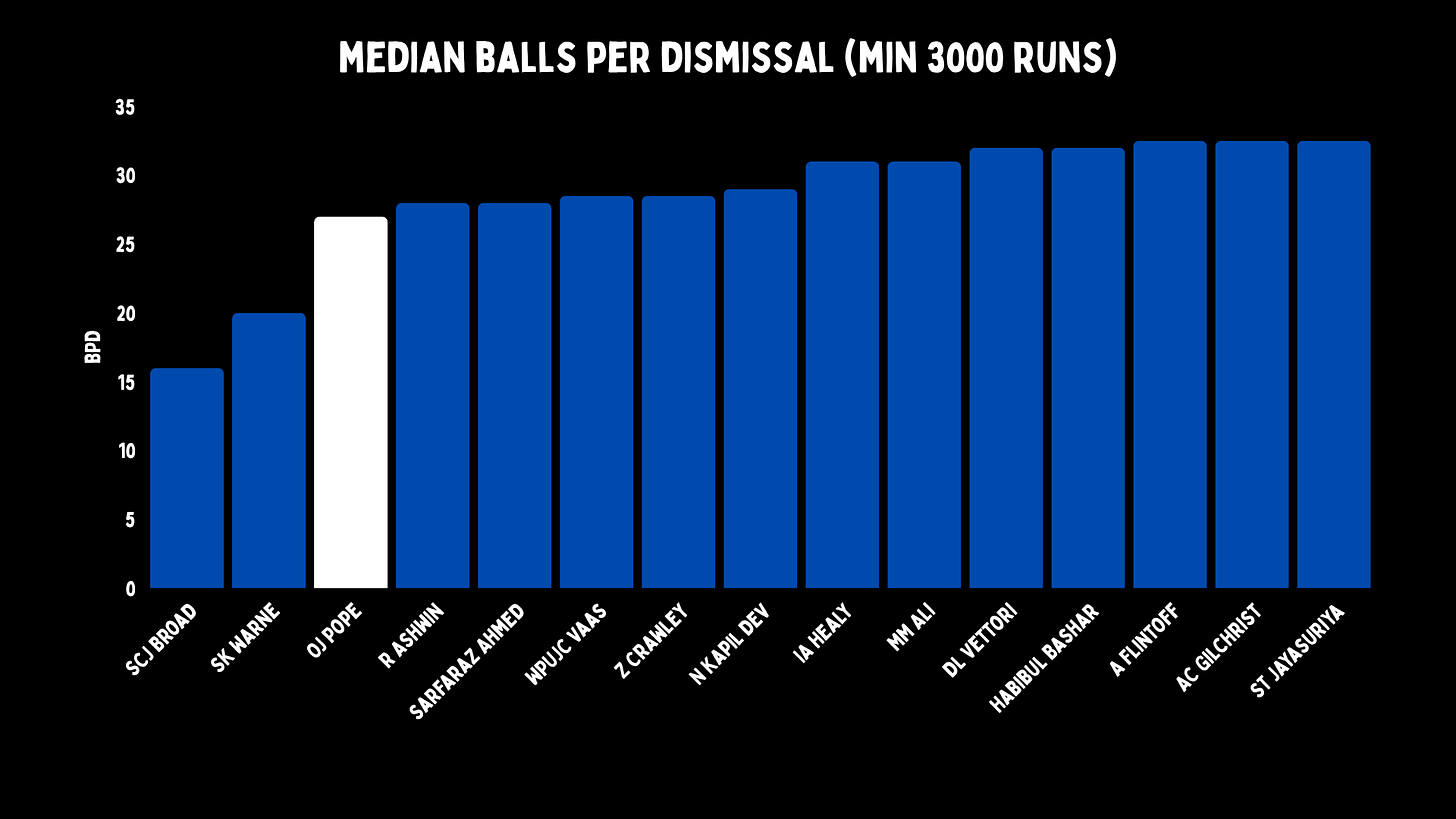

But Amiss, Atapattu and Flower were slow players, at least early on. Pope is Bazballing, and so he has the worst deliveries per dismissal median on record. This means you are more likely to see Pope fail quickly than any batter in the entire history of our sport.

If you take out the top six, the only players who are quicker to be taken are tailenders like Shane Warne and Stuart Broad.

According to median, the average Ollie Pope innings is a camera flash.

***

Steve Smith doesn’t sleep during Tests, and you can track his average by innings and see him getting more exhausted. Everyone thinks it is odd.

Pope told talkSPORT recently that he also can’t sleep during Tests.

It makes sense - looking at his record, Ollie Pope is like a declining stock. With each innings, he gives you less.

Tests are long; not sleeping for three or four days is going to affect your performance.

But there are also technical reasons that some batters struggle later in the game. Smith plays across the line, meaning when the ball is not bouncing as consistently, he’s more likely to find trouble.

On an extremely related note: Ollie Pope gets bowled a lot by pace. His stumps being splattered is a meme and a T-shirt.

No one wants their first drop castled a lot. Except that in classic Pope style, it tells you absolutely everything, and nothing. Because the player in Test cricket who has been bowled the most by pace is Wally Hammond - England’s greatest number three. In fact, many of these players are some of the best ever.

So Pope gets bowled a lot, and perhaps that is bad in the final innings.

Let’s check this pattern of declining returns in county cricket. When Pope plays for Surrey, he has no issue at all. Now final innings in first-class is different, as there is one fewer day. In county cricket, he’s got a normal pattern. Pick him for England, and he gets freaky.

It is also not just the fourth innings, is it? If you look at Pope, he has one of the worst records in the third as well. If Test cricket was a one innings game, he’d be one of the world’s best players.

He just cannot get in for the second knock. It’s not like all pitches deteriorate, or that they are so long he’s not slept in four nights either. So this is just totally stupid.

In England’s second innings of the match (so the third and fourth innings of the match), the median balls Pope will face is 19. That is what you’d expect from a number nine. And for you maths fans, it’s just above three overs.

But Pope isn’t just bad in the final innings of a Test, he is historically bad. In an era when his team loves the last innings, and pitches seem to stay whole for longer than ever, Pope is more spirit than flesh. At the end, he’s a batter by name only, a long forgotten whisper.

***

England couldn’t make runs. They were trying blockers at the top in the hope they could at least delay the entry of the middle order. And even that had limited effect. And then in 2020, a fresh-faced batter comes in and makes runs, while also having a great county record to back it up.

England were almost as excited for Pope as they had been for Root a decade before. At the Wanderers in 2020, I’m given an assignment by the talkSPORT producer Jon Norman after Pope’s breezy first innings 50: “Can you analyse Ollie Pope for any weakness?” It was like being asked to vomit on Bambi.

English fans did not want to hear anything negative about their great white Pope. And commentating with me is his Surrey teammate Gareth Batty (who will also later become his coach) and also Surrey legend Mark Butcher.

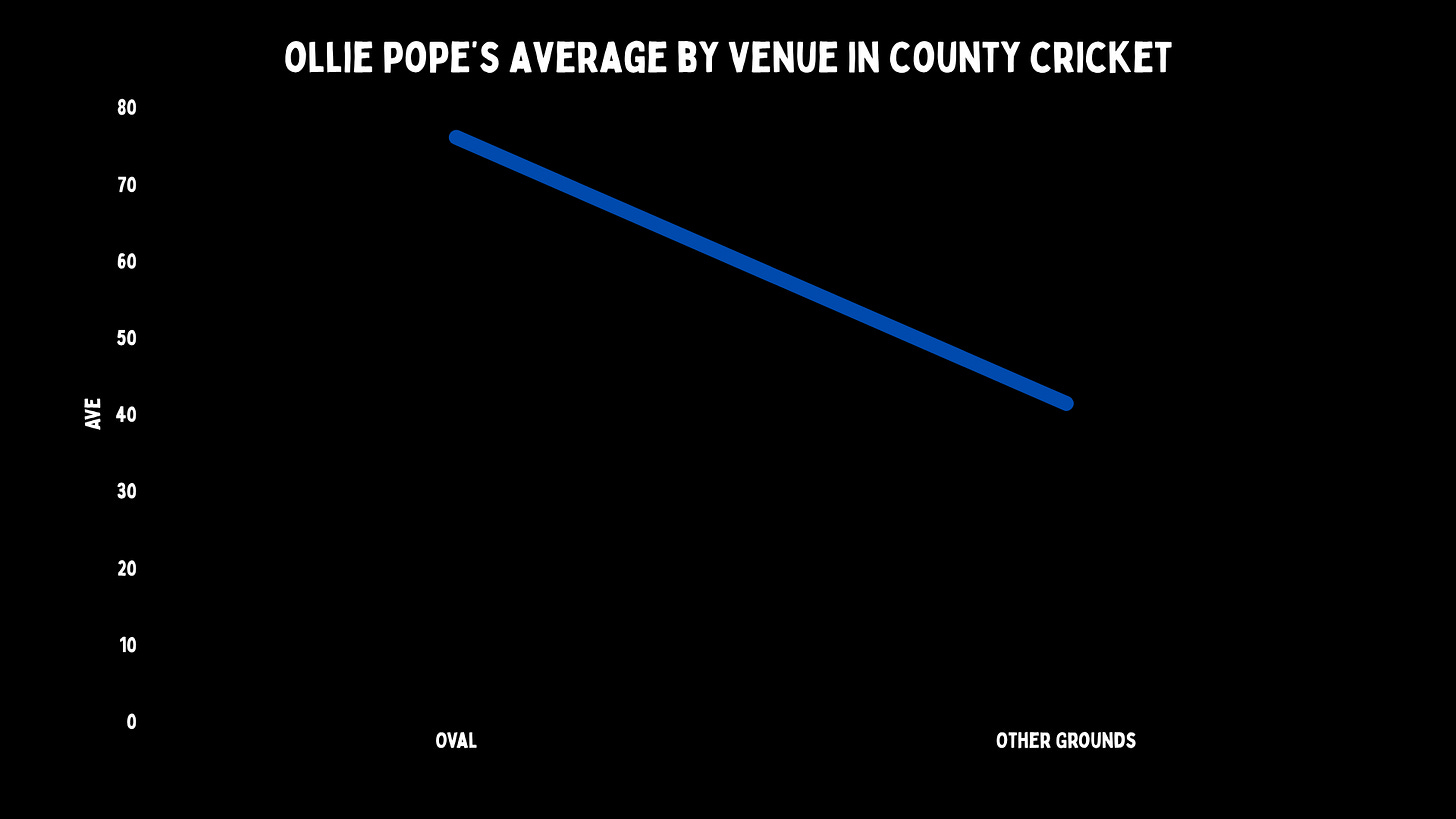

To keep it light, I go through all the fun bits of how good he’s been against seam, and of course his famous record at the Oval, where even now he averages double there than away in county cricket.

So these Surrey boys had seen him make a lot of runs, and now he’d done the same for England. They were very high on him. At that point, only nine players had made over 2000 runs in county cricket and averaged over 60 - including Crowe, Lara, and Sangakkara. No first names required. It was quite the start to a career from Pope. Since then, he’s regressed slightly.

He only averages 58 in the county game now. Making runs in English domestic cricket has not been easy for a long time, and for young local players, it’s been almost impossible. But Pope has been incredible. And you can see that late-career Mark Butcher was pretty handy too.

So Butch knows batting and Pope, and here I was telling him two things: that the young Surrey gun basically couldn’t score when the ball was on a length outside off stump, which is never a good sign, and that his strike rotation against spin was terrible.

Mark Butcher - a good friend who was using some radio licence - suggested I should go away. While Batty added, “absolute nonsense has been spoken”.

But from the limited data I had on Pope, there was a pattern in his play. He scored at 1.3 runs per over when the ball was delivered on a length outside off. That is alarmingly low, and means that teams can really keep the pressure on him as long as they want.

My bigger concern was against spin. In first-class cricket, he could not rotate at all. And that is against mostly English spinners on wickets that don’t suit them. How was he going to go when he went to Asia?

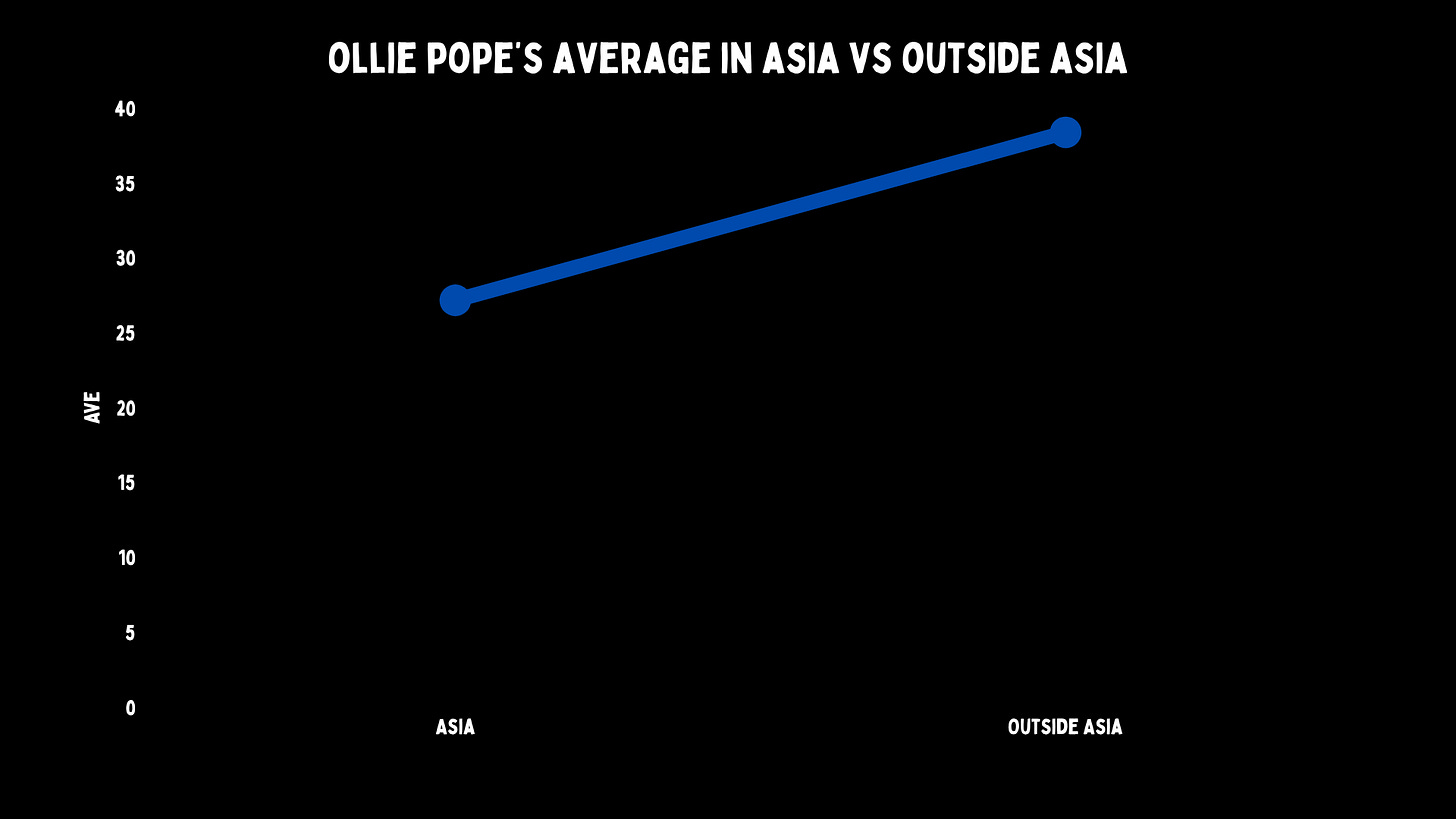

In 15 matches across India and Pakistan, he averages 27. The Indian wickets have been tough, and the back end of Pakistan’s last tour was too. But he still seems to have the same basic issue - of not being able to rotate the strike - that showed up in county cricket all those years ago.

But this is Pope, so of course it is stranger than what you’d think. His problem in Asia is not just spin, it’s also pace. And that might be because of his issue with being bowled, because Asian wickets keep lower. So, he’s been bowled and LBW quite a few times by seamers there.

Against spin, he makes it fun again. This time, by being worse against the ball that turns into him, rather than it moving away.

If you’ve ever seen Pope try to play R Ashwin, you would think you’re watching someone trying to solve a Sudoku while base jumping. He’s about as bad a backfoot player against offspin as any right-hander ever. He gets trapped in front as if every ball is an anxiety laden cluster bomb, whereas he has no issue against left-armers on the backfoot. But on the front, he starts to get shakier, but this is where he’s great against offies.

The kicker is, he runs down the wicket like someone trying to hail a bus that’s already left. He might be one of the worst players to use his feet to spin in the modern game. Perhaps early in his life he was successful, but tweakers in Tests are better and quicker. But he should stay in his crease, at all costs. Down the wicket lies only pain.

Pope is also not only poor at rotating the strike in terms of speed, but also staying in. Your high average should be the shots that are low risk, but his are the attacking ones. Pope can hit spin, he cannot milk it.

Clearly, things change a lot when McCullum comes in. Before, he was often stuck and then played the odd boundary shot. After, he became a reverse sweeping zealot running down the pitch. And now, he is somewhere in between. Spin is still not his thing, and probably never will be.

Pope and county cricket might make more sense now, because it’s a competition with few spinners, and even less wickets that suit them. It’s where fast-medium and below seamers try to take your outside edge for packed slip cordons, and there are no fifth days.

If Pope bats in the fourth innings, the wicket should still be holding up. There aren’t many quick bowlers to blast through him. If strike rotation is his issue against the turning ball, then the spinners there are more likely to deliver a loose ball for his attacking shots.

After ten Tests, Ollie Pope averaged 43. He had played incredibly well in South Africa, made a half-century in New Zealand and was nine short of a ton at home against the West Indies. By his 24th, he was going at 27. He’d gone from prodigy to liability.

Maybe Pope can never live up to the early hype through no fault of his own - it’s just he isn't perfectly built for Tests. There are good bits, but his game is like a kid’s doll made up of all the leftover parts forgotten under the bed.

***

Pope has always been an uneasy Bazballer. Like he was given a script he didn’t quite agree with, but thought he could ad-lib his way through.

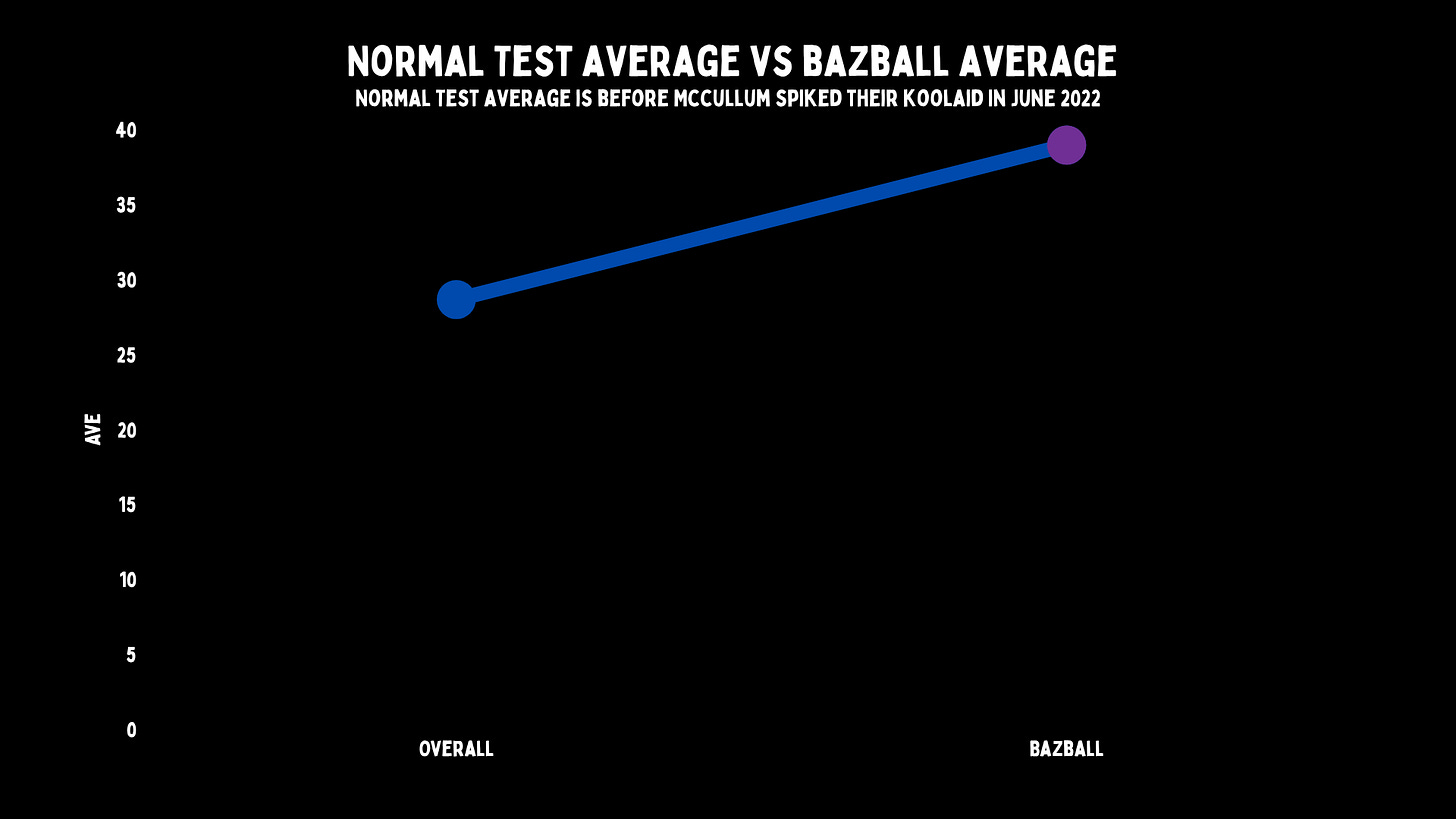

For all the fireworks, champagne and cigars, his average was 28 before Brendon McCullum took over and changed Test cricket. Since then, it has been 38. That is a massive leap.

If you take out the huge scores against the non-WTC teams, it’s 34. Again, it is still better, but it hasn’t really transformed Pope into something unrecognisable from before. Just a slightly more devil-may-care version.

In the last WTC cycle, Pope made over a 1000 runs, but it was at an average of 31. And his strike rate was good, but not revolutionary.

Lots of his pre-Baz Tests were from when he was young. Players usually take time to start making Test runs. Pope was due to make more in the back end of his 20s than at the beginning. Most importantly, he’s not yet reached his peak. He is currently 27. Maybe all of this is bum fluff on the way to something more.

If we factor in his age, we assume he’d start to make around seven percent more runs in the period of Bazball, than in his early 20s of normal cricket. So he’s certainly outperformed the expected age curve.

But there is one thing Pope has to get used to because of modern cricket and the way his team plays. Only Aiden Markram has ever played in fewer draws. Almost all of Pope’s matches are results. There is nowhere to hide, almost every knock is important, or needed, and on a pitch where bowlers get wickets.

Lowest control % since June 2022 (min 1000 BF)

And how do Pope and England combat this? By whacking, moving Pope’s strike rate from 50 to 70. And because of that, Pope has one of the lowest control percentages in cricket. But not in his team, because there are so many other players from England here. This is their plan: disrupt, cause chaos, make their players think they are ten feet tall. Bazball has weaponised confidence. Pope’s career exists largely because he believes their hype about him.

How has that affected Pope? Before, he would make 28 off 56 deliveries per innings. Now it’s 34 from 49. Because only in Bazball could someone hit a six from minus seven deliveries.

***

How is Ollie Pope doing this?

His batting is grotesque. He turns to play a reverse sweep, but maybe forgets about that plan, and starts to walk down the wicket instead. A charge and reverse, Bazball in one shot. Pope rarely reversed before - now he’s downing pints of Bazball Kool-Aid, trying shots he doesn’t even believe in.

He’s not very good at the reverse (as Rohit hints loudly) and is almost out several times. Also, despite playing a lot of them, he doesn’t score that much. But he’s up against Axar Patel at one end, with R Ashwin at the other. He can’t play either traditionally, so he’s trying to disrupt.

This means that at one point he ends up with his hands and knees on the pitch, after trying to defend.

From nine innings on Indian soil, he has barely more than 150 runs. In this knock, he puts up 196. England only made 246 as a team in the first innings.

And the big question from the Indian side is simply, how is Ollie Pope doing this?

India have played Bazball once, they have been preparing for months, they know that the chances of England being able to handle their bowlers on their wickets is really low. They just need to execute and wait for the wickets.

Of all the batters, they worry the least about Pope. Not through arrogance, just experience. They have several plans for him - he struggles with spin, even more so in Asia. And seamers clean bowl him, so with Jasprit Bumrah in the game, that feels inevitable.

Most days, they would be right. Today, that doesn’t happen, so Ashwin looks flustered, Jadeja can’t work out what to bowl, Axar is toothless, and India get ragged in the field. At the breaks, as a team, they keep asking the same question: “How is Ollie Pope doing this?”

62% of his total for the series comes in that knock. India lose the Test, and Pope doesn’t make another run on that tour as six players score more than he does.

This is not a normal batter. His record looks like it was put together by a bunch of toddlers. There is nothing standard or straightforward about Ollie Pope. He is a miraculous bastard child of modern batting. Maybe this weirdness is our future. A weak-chinned chimaera patrolling cricket’s run barren landscape feasting on scraps.

How is Ollie Pope doing this? Maybe, we’ll never know.