The new punk rock number fives

Number fives are the rockstars of the batting order right now. Live free, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse.

UK readers can get their copy of the book here:

Harry Brook has a control percentage of 20% after five balls. It means only once did he actually follow through with his intended plan for a delivery. The score was 25/3 when he came in to bat in the eighth over. Off his third ball, facing Siraj, he dances down the wicket to try and smash the ball past mid-off. He misses it. Nothing matters.

Harry Brook is not a number five. He’s vibes and screaming, nine-inch nails running down a chalkboard, someone riding a flaming motorbike through a desert with no helmet on.

Rishabh Pant is not a number five. He is too sexy to be in this spot, he’s like a burlesque dancer bringing your Deliveroo. He is too limited, cavalier, and has to spend his own innings telling himself to behave like a grown-up. It's an odd sight, like watching a young boy wear a suit and tie for the first time, while he can't stop tugging at his collar.

Your aunty might go on about Shivnarine Chanderpaul and Steve Waugh, but the number five slot has changed. It’s bolder, brasher, and louder than ever before. It used to be filled with batters who were a little limited against the new ball, now it’s being taken over by guys who “run through lightning with their dick out.”

This is the age of the attacking fives.

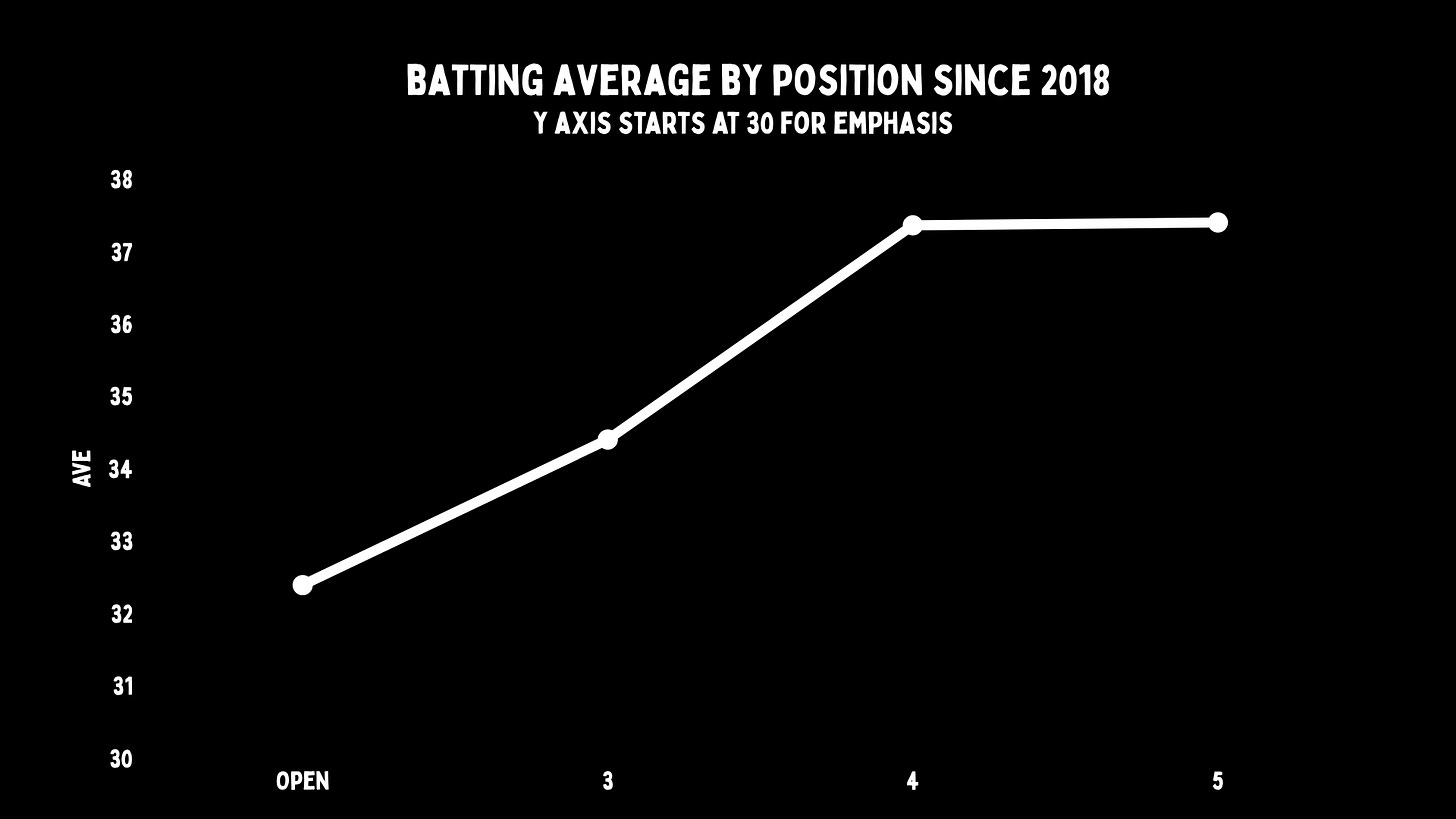

And despite this new method of whacking the ball everywhere, number fives average the same as number fours since 2018, which is when the pace playing pandemic starts. That is usually where the best batter is. Number five has never been that, yet they have averaged as much as fours now. Travis Head, Harry Brook, Rishabh Pant and co are playing shots and scoring runs at a rate we haven’t seen from this position before.

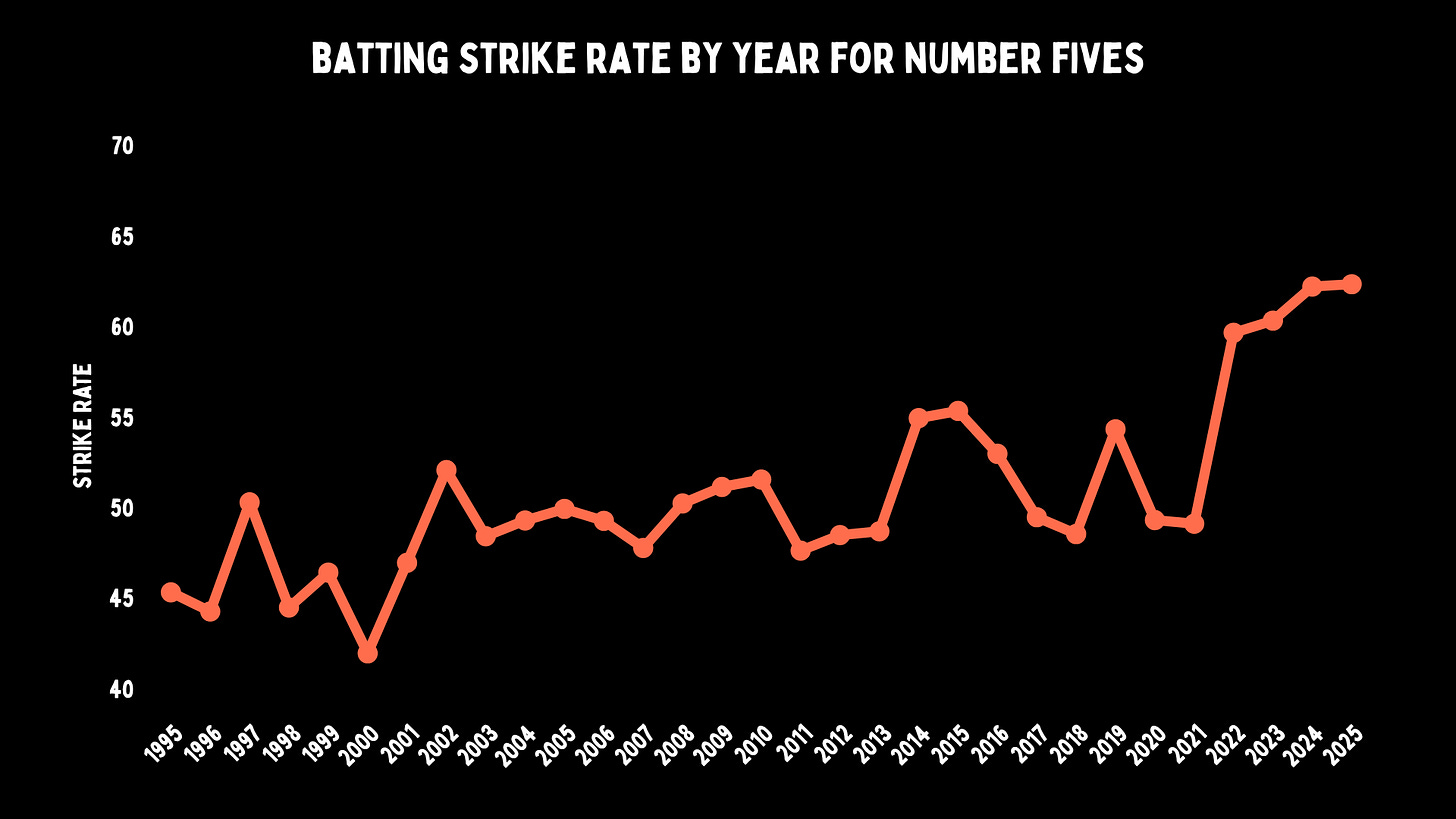

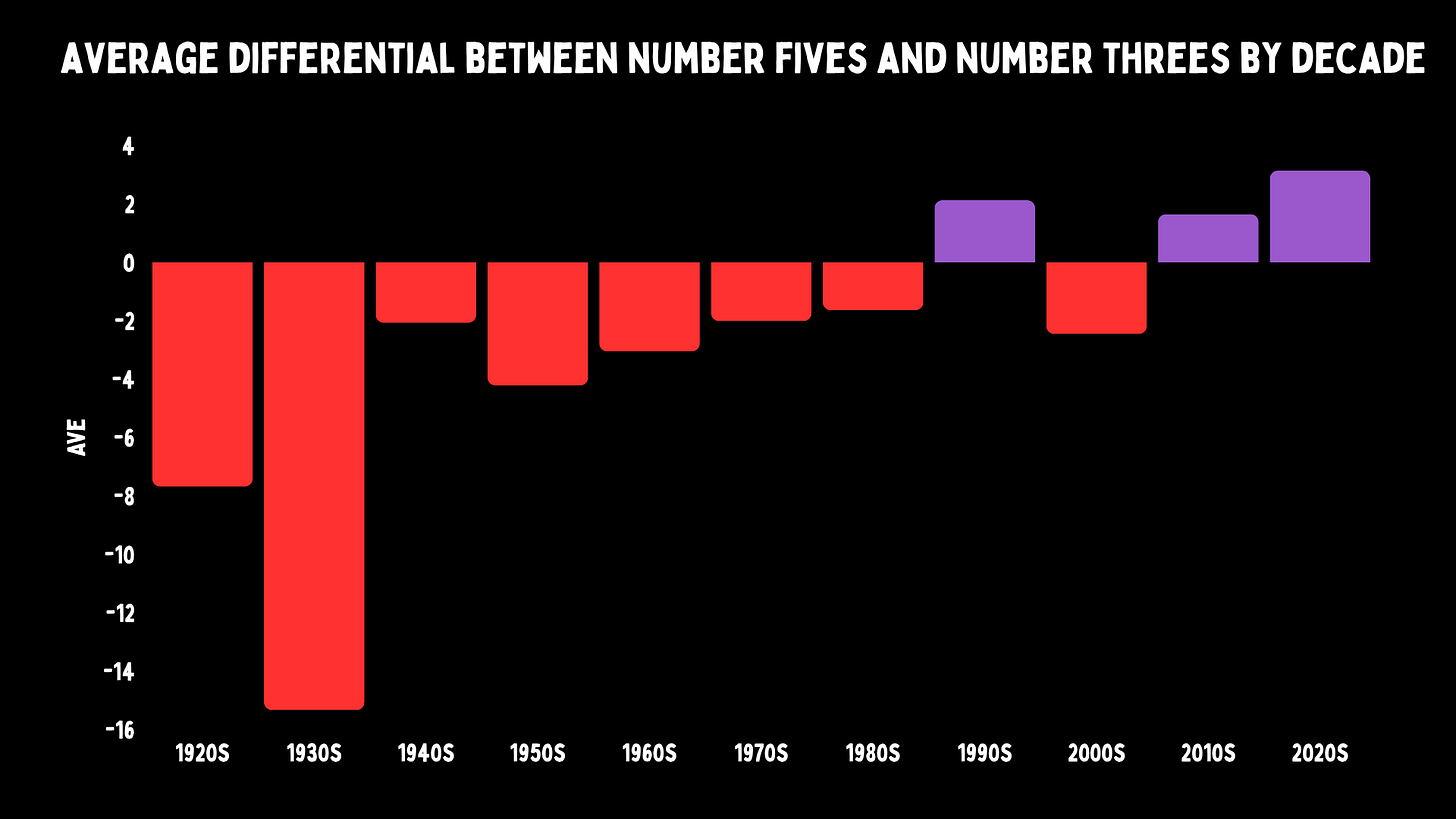

It isn’t that number fives haven’t had great years in the past. From 1920 to 1994, there were seven years where they topped the charts. However, that number has increased to 11 in the last 31. That is a seismic shift in cricket culture.

In the mid-90s, we saw the change. Waugh, Flower, Yousuf, Azharuddin and Thorpe stand out. 2008-14 is another period of absolute domination, with Chanderpaul, de Villiers and Clarke at the forefront of it. All these batters are all-time greats, or at the very least, greats for their countries.

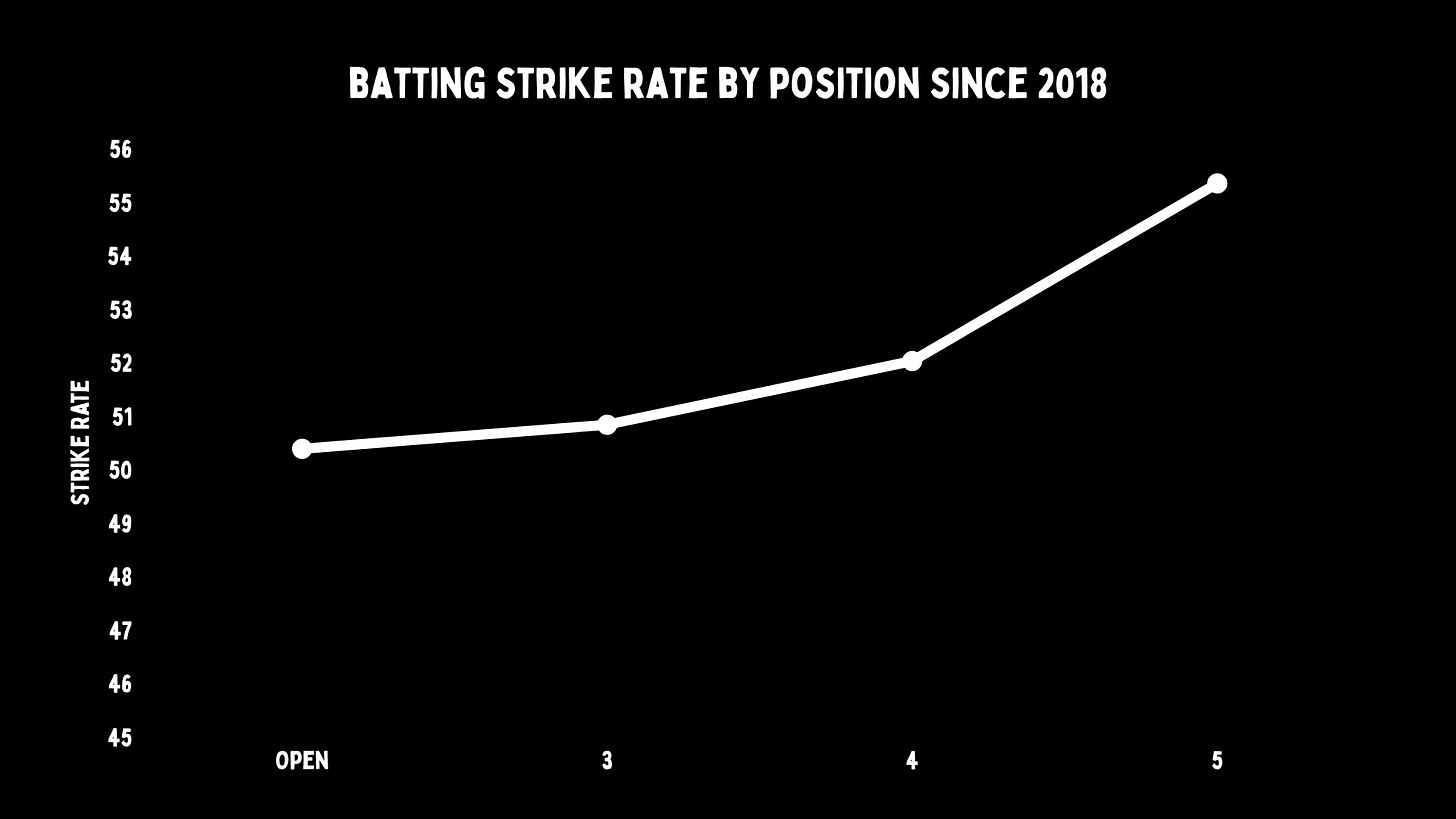

But the way the fives have attained success since 2018 is a bit different. They have collectively been the fastest scoring batting position.

And that has become even more prominent over the last few years. Teams nowadays look at their number five as the player who can do the most damage.

Test cricket has gone from the grit and grind nature of Waugh, Flower and Chanderpaul to the chaos of Pant, Brook and Head. Pant’s run down and heave is the new soft-handed block for a single from Waugh.

Why wait for a bowler to get you out, when you can just scoop him over second slip's head and look good doing it? Number fives are the rockstars of the batting order right now. Live free, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse.

We can split 1995 to present in three distinct eras. The late '90s were a bowler’s paradise - fast, mean, and slightly unhinged. Then came the batter's golden age: big bats, flat decks, and boundary ropes practically in the slips. That lasted until the bowlers got their revenge - wobbleballs, result pitches and a reinforced seam that never dies.

Compared to the previous 17 years, there’s a significant drop-off in the averages of almost every bowling position, and a relatively smaller one at four. Clearly, bowling attacks have been dominant in the last seven and a half years.

The first period had better bowling at 1, very close from 2 to 4 and worse at 5. And you might wonder why the depth of the attack matters. It’s because a bowling side wants to be able to put pressure on the opposition’s batters even after their main guys take a break. That is Test cricket’s big difference from first-class. In the domestic game, you are surviving one or two bowlers, often for only a couple of spells. Test cricket attacks are relentless. That has been the case in the last few years.

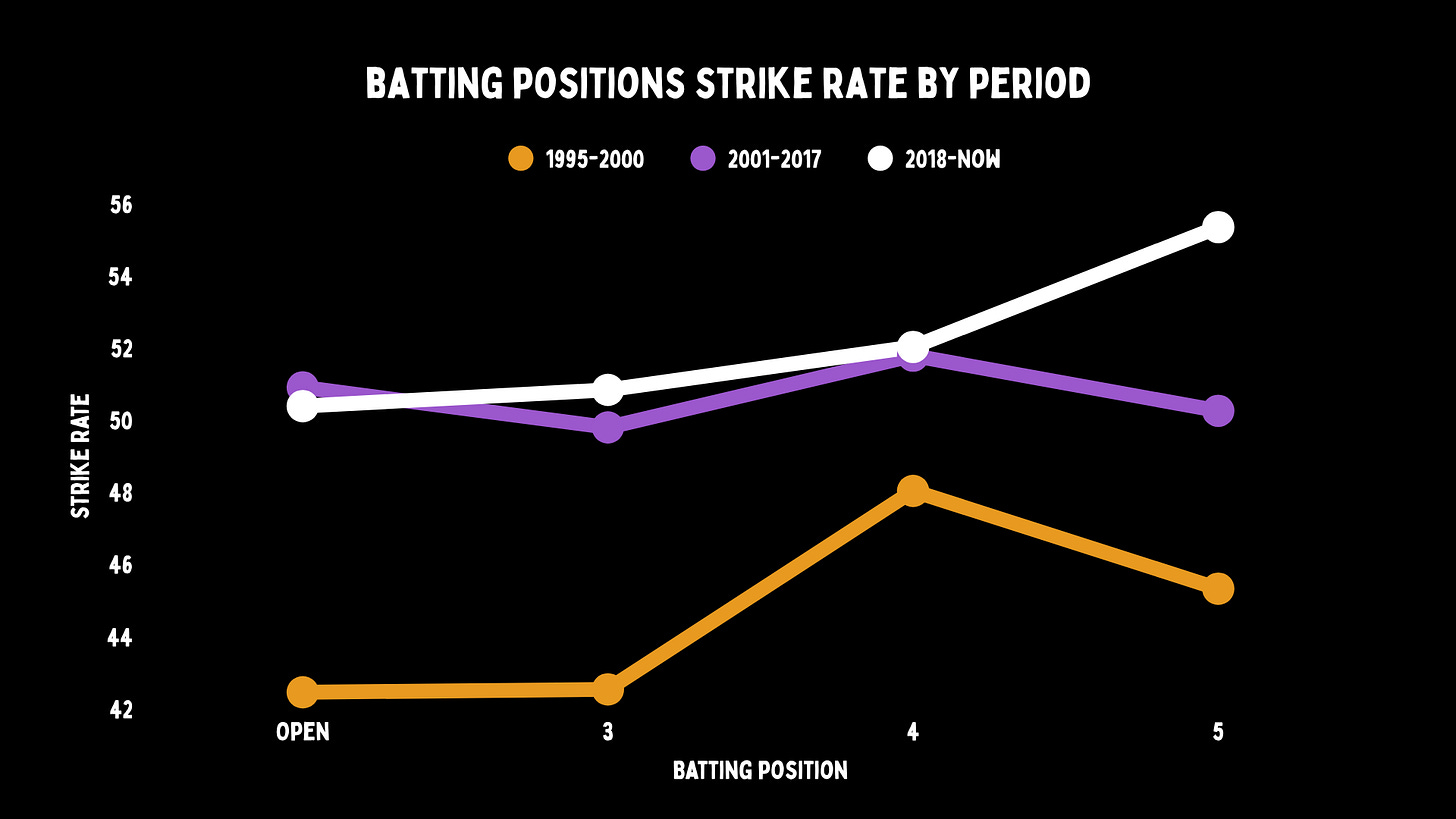

When we look at the batting, we really see this. Although the top three batters have similar returns, number fours and fives are worse off in the modern era. But compared to the batting-dominant period, number fives have the smallest drop off.

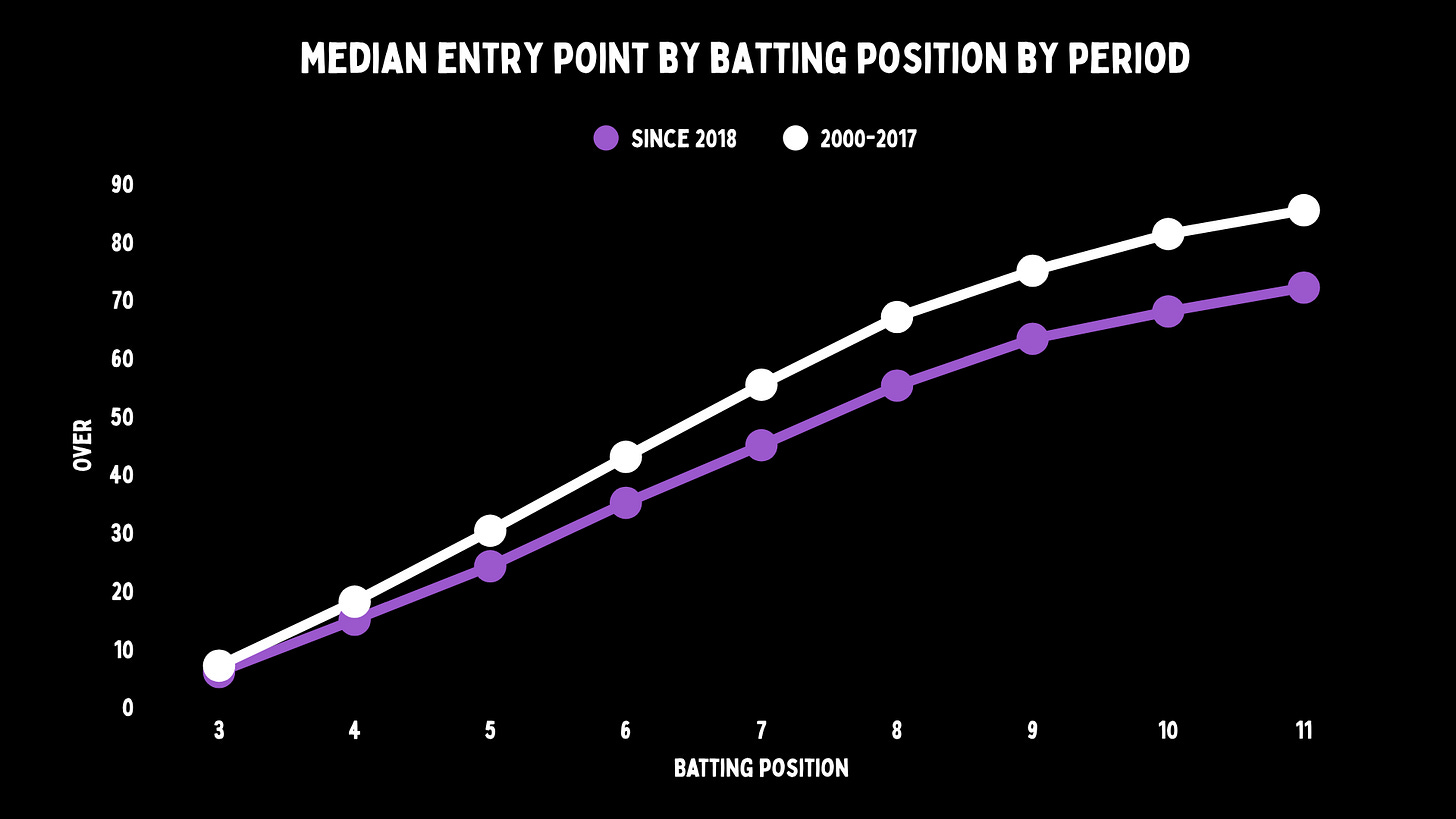

Parachuted into a wildfire, number fives are clocking in earlier than ever. In the wobbleball era, the median entry point for them is the 25th over. That is about six overs sooner than their counterparts in the previous 18 years. It means they face a relatively newer ball in an era against better and deeper bowling attacks, and with teams hunting for WTC points by making result pitches at home.

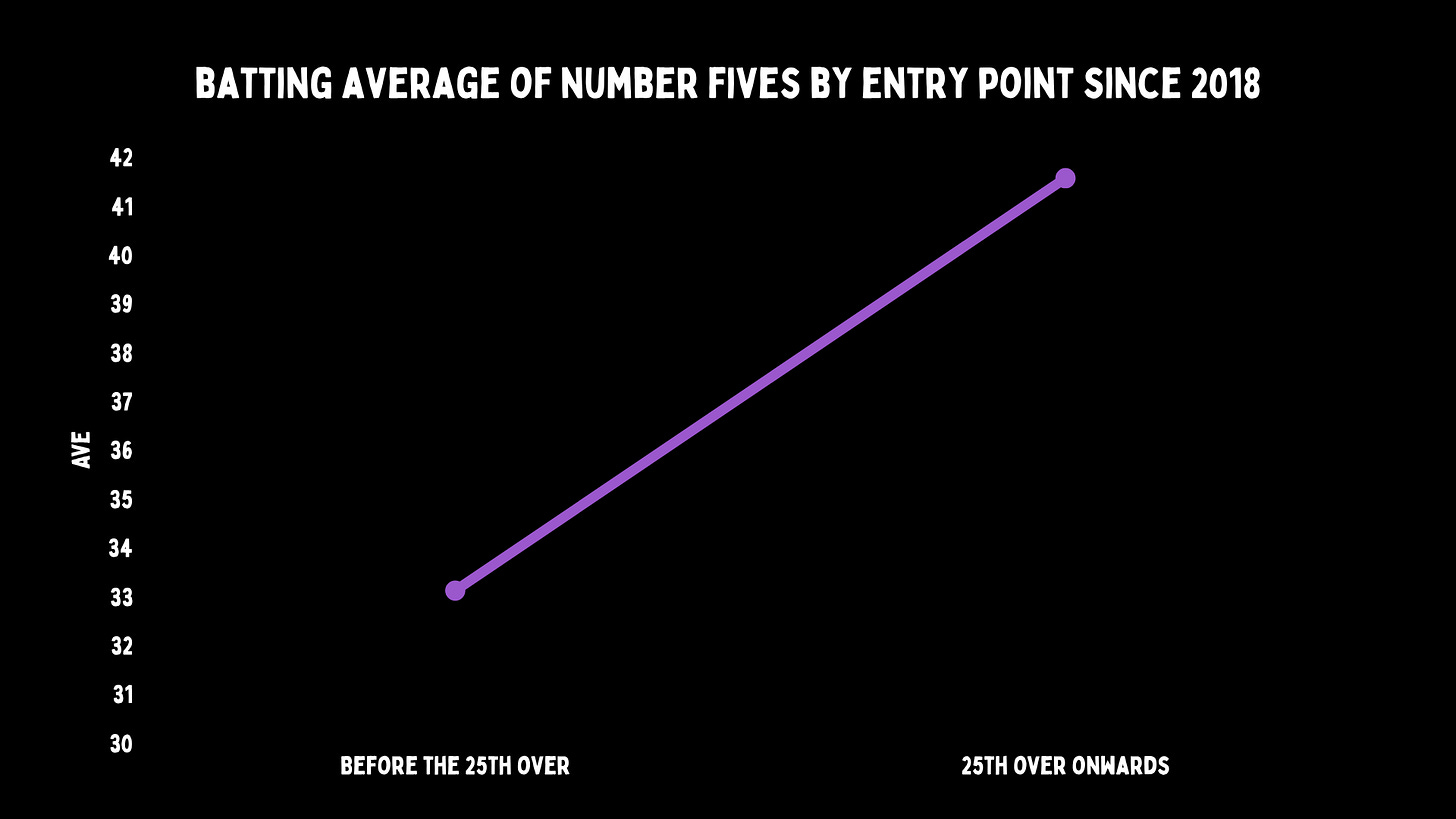

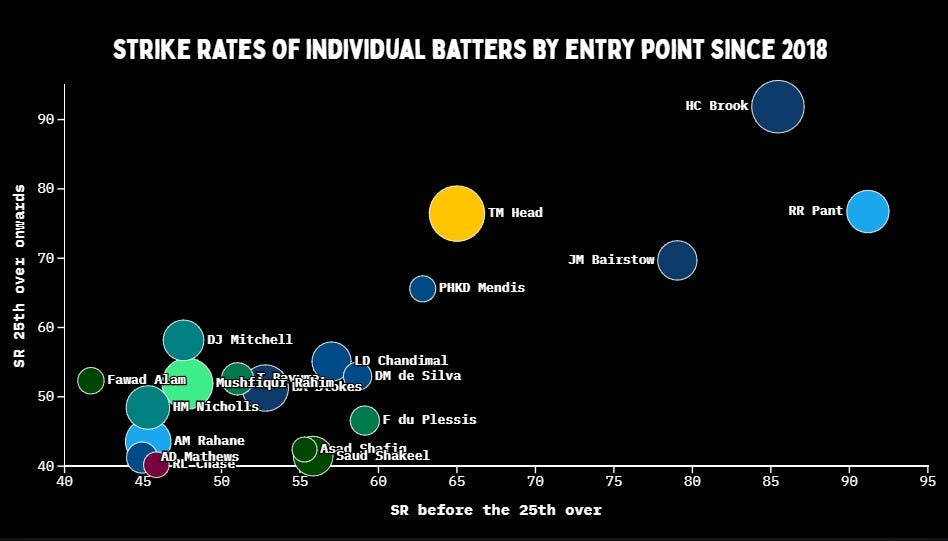

And how does that affect their batting returns? When they come in before that, the global average is 33. That rises up to nearly 42 when they come in at a more favourable entry point. But even the various number fives have different kinds of patterns.

For instance, two Pakistani batters - Fawad Alam and Saud Shakeel - actually perform a lot better when there’s a bit of a crisis. Jonny Bairstow and Ajinkya Rahane also have a similar pattern. Angelo Mathews does well in both cases, but numbers suggest he seems to prefer the tougher challenge. Pant and Bavuma are the opposite, they do well when they come in early but are next level with a set platform behind them. Brook has been almost as good, regardless of when he comes in. We see that a bunch of batters have much better averages when they come in against the older ball.

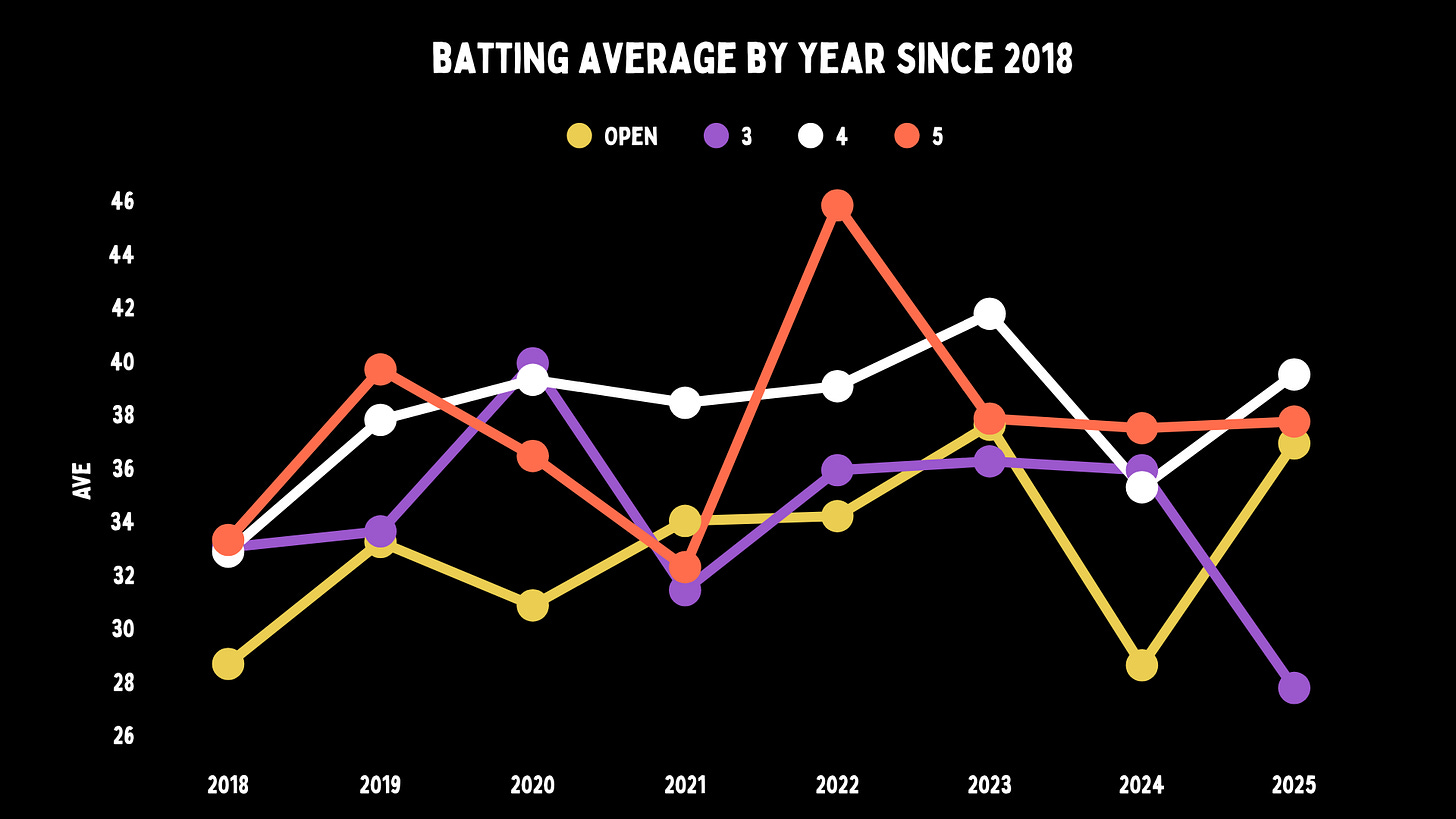

So they come in early, but still do well. 2018 was when it all started. By 2022, it was the Summer of Jonny: Bairstow was hitting like he was mad at the ball. Suddenly, number five is a cultural revolution. In the eight calendar years in this time period, number fives have the best average in 2018, 2019, 2022 and 2024. Their collective runs per dismissal in 2022 was better than any other batting position in any calendar year in this duration.

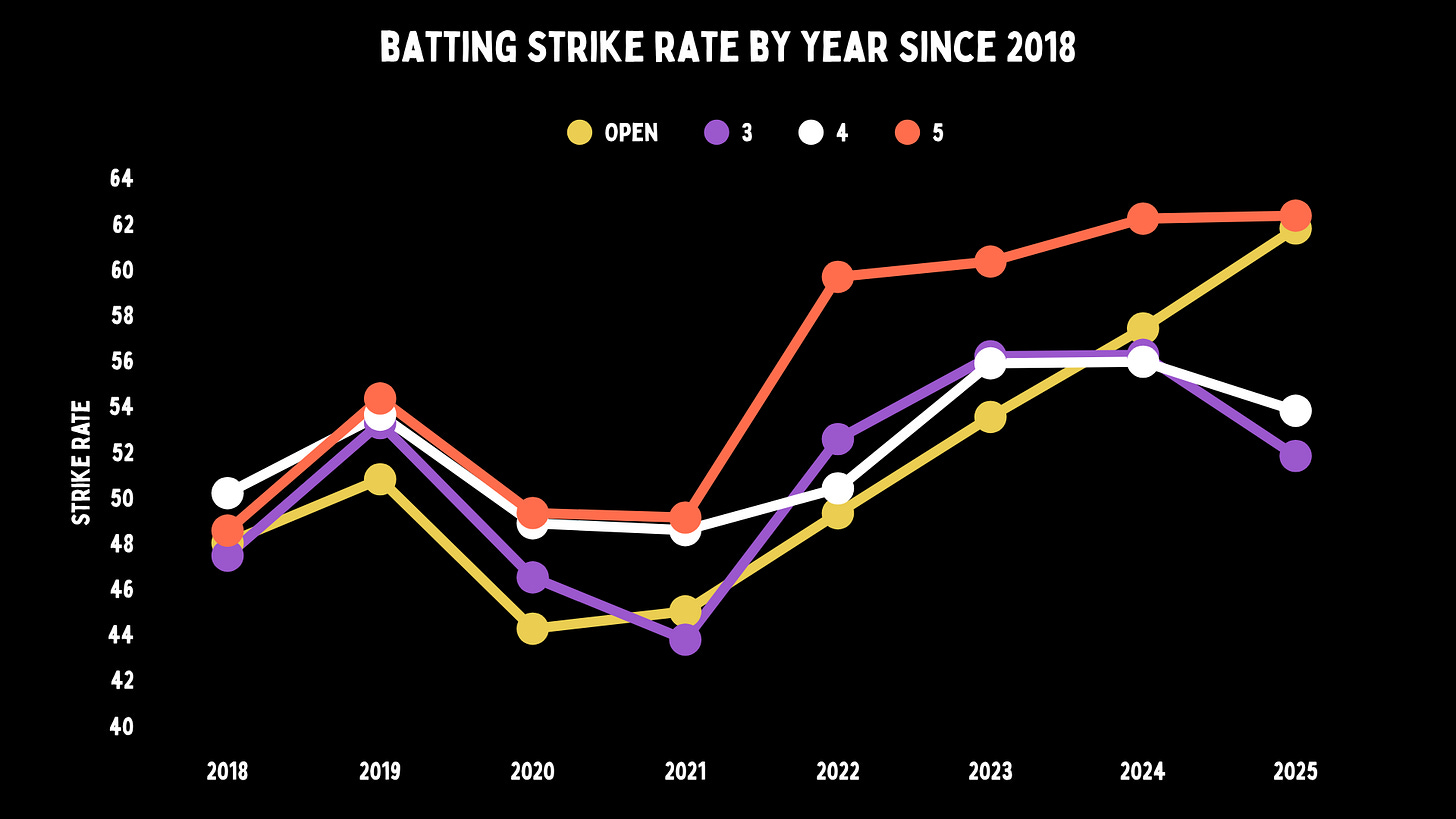

Apart from 2018, they also have the highest strike rate every year. For a good three year period from 2022 to 2024, they were outstriking the others quite comfortably. This year though, openers have nearly caught up with them.

When you think of fast-scoring batters at present, the obvious names - apart from Ben Duckett and a few other Bazballers - Pant, Head, and of course, Brook. All number fives. Plus, Kamindu and Chandimal also strike at above 60 runs per 100 balls in that spot from 2022. That would be fast in another era, but seems normal now.

There is a strong case to be made that they’ve all been among the best batters of their own sides at various points. They rattle bowling attacks because of their strokeplay, but we know they’re not just blind sloggers and that there is a method to their madness.

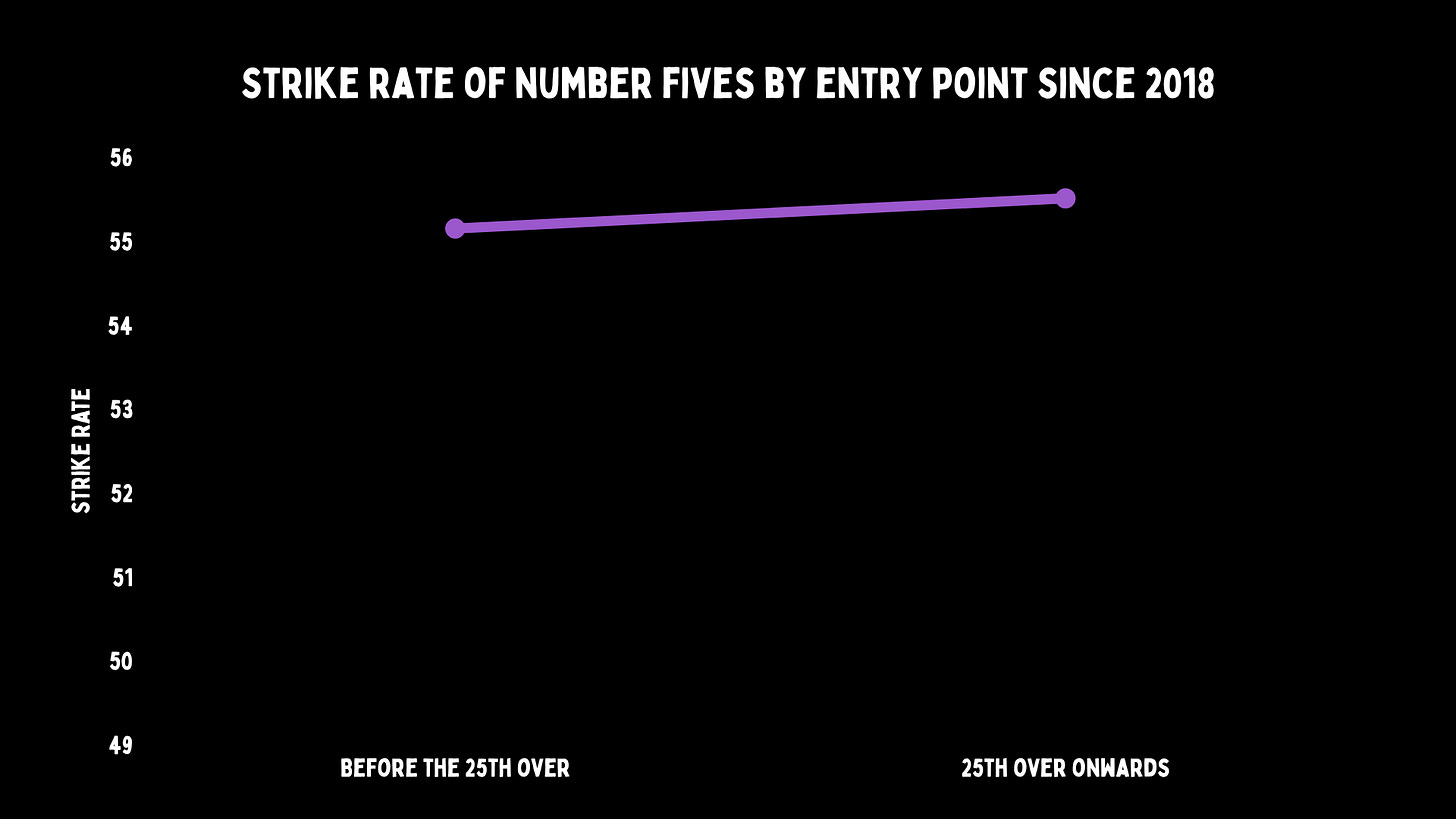

There’s a drop of nearly nine runs per wicket when batters come in before the median entry point, because it’s tricky. But the strike rate in those knocks is nearly the same. Many of these guys just hit back, hard. Early entry takes some runs off, but these guys are driving into a storm at 200 kmph with the stereo cranked all the way up.

Take Pant for instance. His strike rate is about 15 more when he comes in early. His way of dealing with a crisis is by counterattacking even more. He’s a firefighter using blue flames to attack red ones.

Pant’s solution to early chaos is escalating it. Brook doesn’t care either way. These aren’t just aggressive players like we had in the past. This is a form of batting by disruption.

Bairstow, Saud, Asad Shafiq and Faf du Plessis have a similar trend as well. Brook, Head and Mendis bat faster when they come in later, but they’re amongst the quickest-scoring batters even otherwise.

The run rate trends have changed a lot from the previous two eras, especially the latter half of the 1990s. Back then, fours were the quickest, and fives struck at just about 45. In the 17 years to follow, scoring rates were relatively more uniform across the board. In the last seven and a half years, fives have seen their strike rates boosted the most.

Three of the last four decades, number fives have averaged better than the players at one down. This decade is the biggest difference ever. Right now, we are living in the world of the false threes and the attacking fives.

Pant and Brook at five is strange. It’s like throwing a cat in a bathtub full of kids. Someone is getting hurt. But there is a reason modern batting looks like this.

There is a clue as to when number fives started getting good, which was in the mid 90s. But wait, we need to go back further.

When cricket started, it was obviously dominated by English thinking, which was in fact dominated by the English weather. In seaming conditions, you probably want your best batters as high up the order as you can to nullify the moving ball, and allow for the other batters to come in later. But other cultures don’t always have as much carnage up top. So why would they want to waste their best player in the top three against the dangerous ball?

So the first move was the best batter going from three to four, which we saw through Sachin Tendulkar batting batting at second drop. A generation earlier he was probably at three. Then Brian Lara and Jacques Kallis moved there. That change started to happen in the mid 90s. And what do you know, it’s when we saw number fives get good.

Number three has never been further removed from the best batting spot. In current cricket, we either have these false threes, backup openers or middle order players inserted up top because first drops aren’t making runs in domestic cricket. The false threes we see now - Jacob Bethell, Wiaan Mulder, Moeen Ali and Raymon Reifer are directly related to the fact there is more batting talent coming in later.

So when the number three position changed, so did four, and so did five. There was a chain reaction down the order. So that explains the more runs, but not the attacking.

Runs per over dipped at the start of the pace playing pandemic. Teams tried to defend it, but this new style of bowling cut through them quickly. Then they decided to attack. They are still going out fast, but they’re scaring some bowlers as well. And in the last few years, the entire world is attacking more now.

This is simple economics. You used to make your money batting for Test cricket, whether that was attack or defend, and hopefully the perfect blend of both. But now the market says attacking shots are worth more, and so people are much better at playing them.

A generation ago, when a bowler was attacking the outside edge on a length, the batter would try to knuckle down and get through it with leaves and soft hands. Harry Brook is just as likely to slog the same delivery over long on, while Rishabh Pant might run at it. Both are thinking the same thing, if they pull this off, the bowler will not be able to automatically deliver their best ball.

And then you have to add in the changes in the ball. The wobbleball and the reinforced Kookaburra means the seam lasts longer and ensures that wickets fall earlier. Meaning that hiding your best player at number four - 90s style - no longer works.

The logic is almost mathematical. If you shift your most talented batters down the order - because batting early is treacherous - and simultaneously create a system where the biggest financial rewards go to those excelling in limited-overs formats, you’re engineering a particular outcome. A generation of highly skilled number fives, all trained to drive fast on icy roads.

The equation looks something like this:

(Best Bat ↓) + ($×WB Format Bias) ÷ (Early Ball Chaos) = 💥 @ 5

Or, as your Excel friend might put it:

=IF(TOP_ORDER=MESS, PUT_PANT_AT_5, CRY_LATER)

But this isn’t about maths, it’s about vibes, rock ‘n’ roll batting and just getting shit done. Your grandpa might have nudged, but these kids slap: Test fives are fighting fire with Molotov cocktails. They are making runs, though, and even when they fail, they often leave us good-looking corpses.

Rishabh Pant and Harry Brook aren’t traditional number fives; they’re punk fives.