Attack of the Killer Bs: When West Indies won the Champions Trophy

A decade before 2016, there was Courtney Browne and Ian Bradshaw. Remember those names.

The game started with Ian Bradshaw bowling to Marcus Trescothick, and Courtney Browne donning the gloves. In 2004, these were not three of the biggest stars in the world. But they did give us one of the best finals in ICC history.

You might have heard of Trescothick; he’s a pretty well-known cricketer. But if you know the other two, you’re a Champions Trophy Truther.

Collis King and Carlos Brathwaite were the main “remember the name” players who gave the West Indies a trophy. Browne, a backup keeper with 66 international caps of which 46 were ODIs, somehow played in one World Cup and two Champions Trophies. And Bradshaw, a left-arm seamer, played in 67 internationals (62 ODIs).

Trescothick is still talked about in cricket for many reasons. But Bradshaw and Browne have this one moment. It is quite a moment though: when West Indies pulled a tail-end heist to take the Champions Trophy from England.

This game was 21 years ago. If you want to know how far back that was, in those days, Chris Gayle had working hamstrings and was the young pup you placed in the covers.

This was not a battle of the titans. In the previous World Cup, neither side made it to the Super Sixes. And suddenly, they were in the finals. England had really struggled to be a force in white ball cricket since the balls stopped being red. West Indies had a great side throughout the 80s and 90s, but somehow could never get it together for a major tournament. This was not a major trophy, and this was not one of the great West Indies sides. Their endless bowling run had finally gone dry.

It was not met with incredible excitement that England made the final. Limited overs cricket was taken less seriously there than most places. This tournament had not won hearts and minds, and it was not in the heart of summer but at the end of September.

Because of the time of year, when Brian Lara won the toss, he decided to send England in. Bradshaw and his medium fast left-arm swing took the new ball, and he struck twice. England were 43/2.

They kept losing wickets, one from a ridiculous run out of Andrew Strauss by a foetus named Dwayne Bravo. But that made sense. What didn’t was that Wavell Hinds was bowling, and taking wickets.

He would average seven balls per match bowling in ODIs. He wasn’t a bowler, an allrounder, or even a part-timer. But they kept him on, because it was working. He ripped - although that is probably the wrong word - out the English middle order.

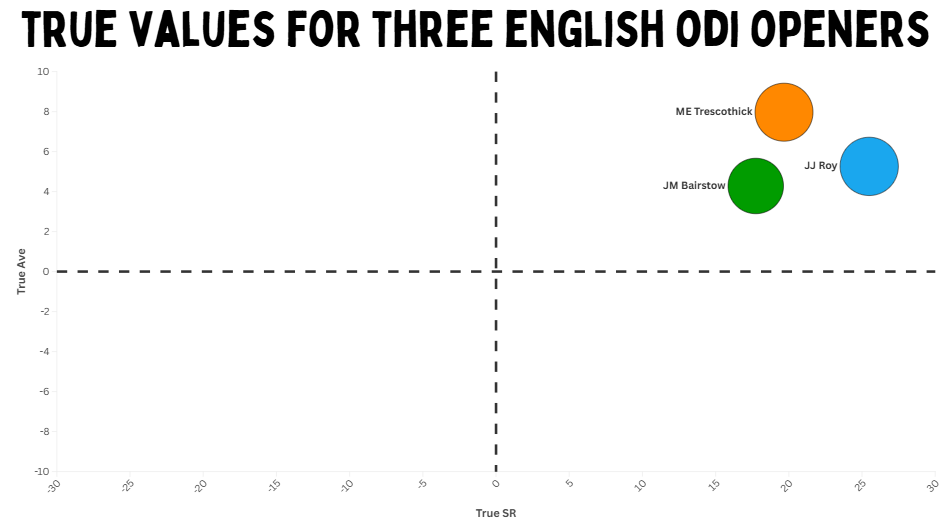

The only player he couldn’t dismiss was Trescothick. In the aftermath of England’s white-ball revolution, the hard slapping lefty has been forgotten. When you look at his advanced stats, he is not far off Jonny Bairstow and Jason Roy territory.

In this innings, he found a way to score boundaries while the rest of the team couldn’t. That is what he’d once done for Somerset, making runs when no one else in his side could do a thing.

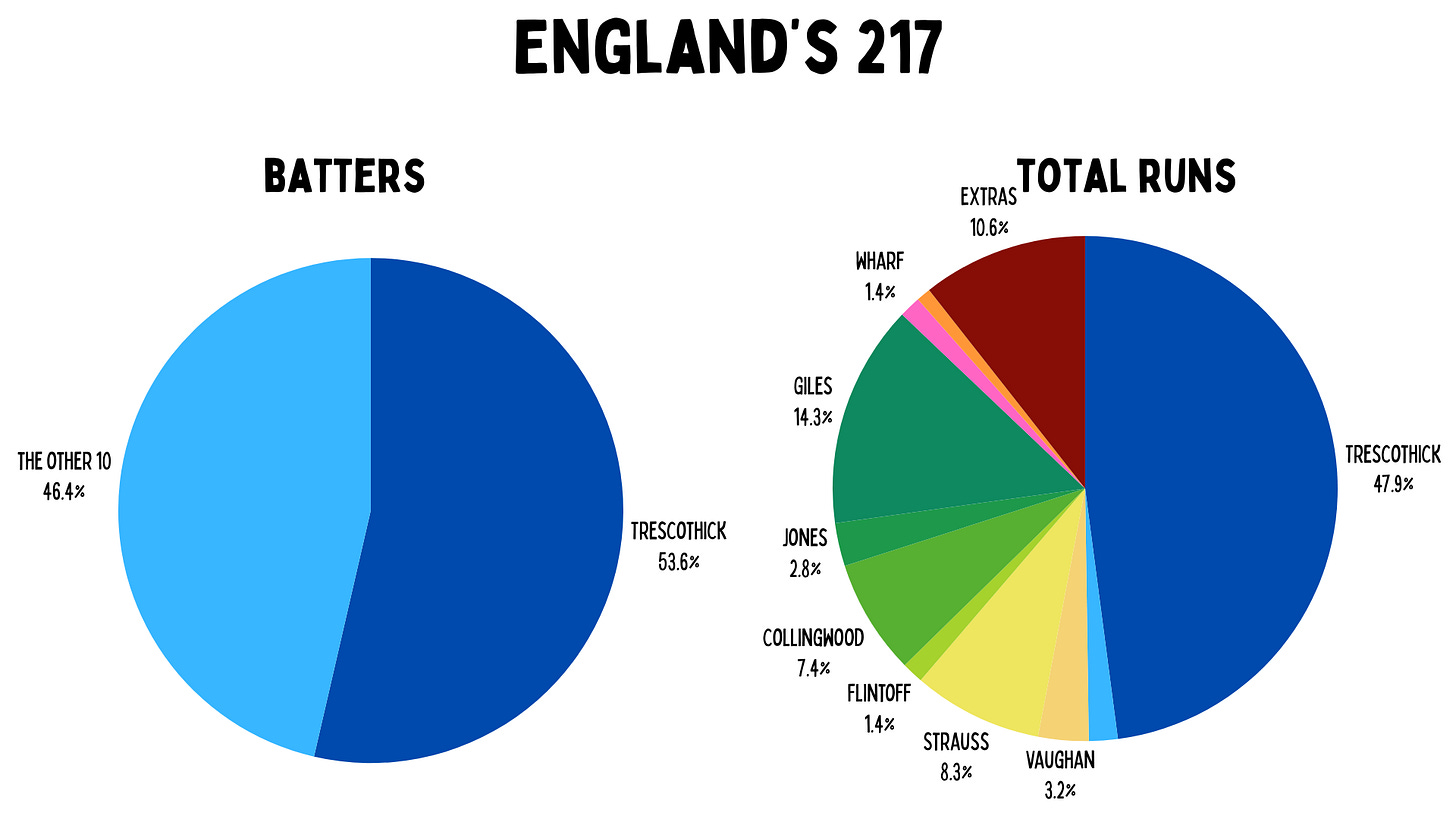

In this knock, he made more than half of England’s runs off the bat. West Indies gifted 23 runs from extras (15 of those were wides). This means England’s third top scorer was the West Indian bowling attack.

But it wasn’t one of them who got Trescothick out, he was caught short when running. England got themselves out that way three times.

England had a total of 217, certainly nothing special. The wicket was still doing a lot and England had a very good bowling attack, with Darren Gough as their leader plus Steve Harmison and Freddie Flintoff.

West Indies had a pretty good batting lineup, too. The destroyer in the first innings, Wavell Hinds, was their worst batter. Opening with him was a young Gayle. At three was Ramnaresh Sarwan. The great Lara after him, with another incredible player, Shivnarine Chanderpaul coming in next. And finally, Dwayne Bravo as well.

That is a lot of talent, and they were all gone. And it was bad, because it wasn’t just Harmison and Flintoff doing the damage. England had given Trescothick the ball. He would bowl the 18th,19th and 20th overs of his career. He would take a wicket, the fourth and final one of his 123-match career. As an ODI player, he averaged two deliveries per game.

Imagine making one hundred runs, more than half the runs off the bat that your entire team made, and taking a wicket, and still not being player of the match.

England always had an endless supply of dibbly dobbly, so Paul Collingwood’s medium pace added two more wickets, and England had the final in the bag when Chanderpaul was out with the score 147/8.

That is when the two Bajans from Barbados, Browne and Bradshaw came together: It was a real life attack of the killer bees.

Browne had played 28 matches, his top score was 26 in 19 innings. In this line-up, he was batting down at number nine. By 2004, it was pretty odd for an ODI keeper to be batting that low.

His partner Bradshaw is often called an allrounder. But he averaged 21 in first class-cricket over his career, and had 24 runs in 12 ODIs (but from four innings) coming in. Neither were batters, and both had earned their positions in the order.

Behind them, it got a hell of a lot worse, because at No. 11 was Corey Collymore and he couldn’t bat. Not at all. So all the runs had to be scored in this partnership.

The record for a West Indian ninth wicket partnership at this stage was 68 runs; the Bajans needed 71. England thought they had this game won.

But this partnership found the boundaries and were ahead of the rate. So they could block out the good balls and attack those they wanted.

They also had an incredible slice of luck when Flintoff went straight and full, and for some reason, Browne wasn’t given out LBW. This was before DRS, but the early Hawk-Eye suggests it was about as plumb as you get.

Then West Indies got lucky in other ways too. Balls squeaked through the ring and raced off. Some of their attacking shots raced off the bat and beat boundary riders. And it was pretty clear that England were completely and utterly lost.

Michael Vaughan went from a captain on the verge of a trophy to a perpetual, disappointed dad pose. Each boundary was followed by him looking more bereft of ideas. He had three strike bowlers, but none of them struck. And in the end, it was Bradshaw’s square drive that won the game with seven balls left. This bowling attack led by Wavell’s wobblers, this batting by two Bajan tailenders, had done something teams with Garner, Marshall, Greenidge, Haynes, Richardson, Ambrose, Walsh and Richards had not done since 1979. They held up an ICC trophy.

Courtney Browne, Ian Bradshaw, remember those names.