Rishabh Pant's multiverse

To everyone else, it looks like madness. To him, it feels like method.

UK readers can get their copy of the book here:

Rishabh Pant left his first ball. Rishabh Pant ran down the wicket to his second one and played a dirty big slog that takes the edge of his angled bat and goes over the slip cordon.

There is a feeling that the second one is what Pant does more, but for the next 14 deliveries he barely plays a shot. He dabs the ball into the offside, uses his soft keeping hands to defend balls that end up at his feet, and there are more leaves. For a moment you have forgotten who is batting. It could be any number five in the world, just coming out, playing a normal knock.

Then Pant charges Woakes again, and the bowler almost loses his shins for another boundary.

Rishabh Pant is 11 from 17 balls, he’s played like Shivnarine Chanderpaul for some of it, and Brendon McCullum for two balls. In one universe, he's anchored like Shiv for a gritty rebuild. In another, he’s already Bazballing for 40 off 12. And somehow, both are happening at once.

But Woakes can only remember the two big shots, and so can most of us. So his next delivery is a wide sucker ball.

If Pant was an idiot slogger, there is no way he wouldn’t swing wildly at this. Instead, he kicks at it, like he’s padding up to a spinner in the 90s.

There is seemingly no rhyme or reason to when he attacks and when he doesn’t - Stuart Broad admits this after the day’s play. Watching Pant is like skipping between universes mid-delivery - you’re never quite sure which version of him you're bowling to. He goes from dead batting blocks with a velvet touch to an on-the-run swipe across the line from a wide ball outside off stump in the space of two deliveries.

At times you’re not bowling to a batter, but an iPod Shuffle with death mode.

There is an internal logic and sense to what Rishabh Pant does, but he’s the only one who can read it. Each shot is seemingly disconnected from the last one, like it has a different law of physics applied to it. As if each decision is in its own parallel universe, because of some quantum reaction spawned from one of his shots. His innings consist of string particles that defy the normal laws of cricket gravity and create a multi-dimensional framework.

To everyone else, it looks like madness. To him, it feels like method. Rishabh Pant’s batting is a multiverse.

“Stupid. Stupid. STUPID.” - Sunil Gavaskar, 2024.

He said this during the Boxing Day Test when Rishabh Pant tried to flick a ball over two deep-set leg-side fielders. Instead, he gets a leading edge and it ends up at third. Not at all what he was planning, and even though Australia get some credit for having that fielder out, he was probably there for the upper cut or edge from the swipe across the line.

“You’ve got two fielders there and you still go for that, and you just missed the previous shot. Look where you’ve been caught - deep third man. That is throwing away your wicket.” Harsha Bhogle briefly tries to speak, but Gavaskar takes over again: “Not in the situation that India was. You have to understand the situation as well. You cannot say that was your natural game. I’m sorry, that is not your natural game; that is letting your team down badly. He should not be going in that dressing room - he should be going into the other dressing room.”

In that match, India were 191/5. Australia had made more than 400. Pant was set on 28, with Jadeja at the other end (a long batting lineup to come). And he played that shot.

Gavaskar couldn’t understand any of it. This was not his cricket. It was not his language or tempo. It was an alien attack on all he loved. To him, Pant’s game wasn’t just reckless - it was from a timeline where Test cricket was raised by wolves.

He is not alone. Every Indian fan has a friend or uncle who complains about Pant. They don’t get it. And yes, you can try to rationalise some of it, but when a man is falling on his arse and is caught in a fielding position that is randomly placed behind him, using logic to explain it is like talking to a flat earther about how gravity and planetary motion could only exist on a spherical planet. They are just seeing what looks like a flat horizon.

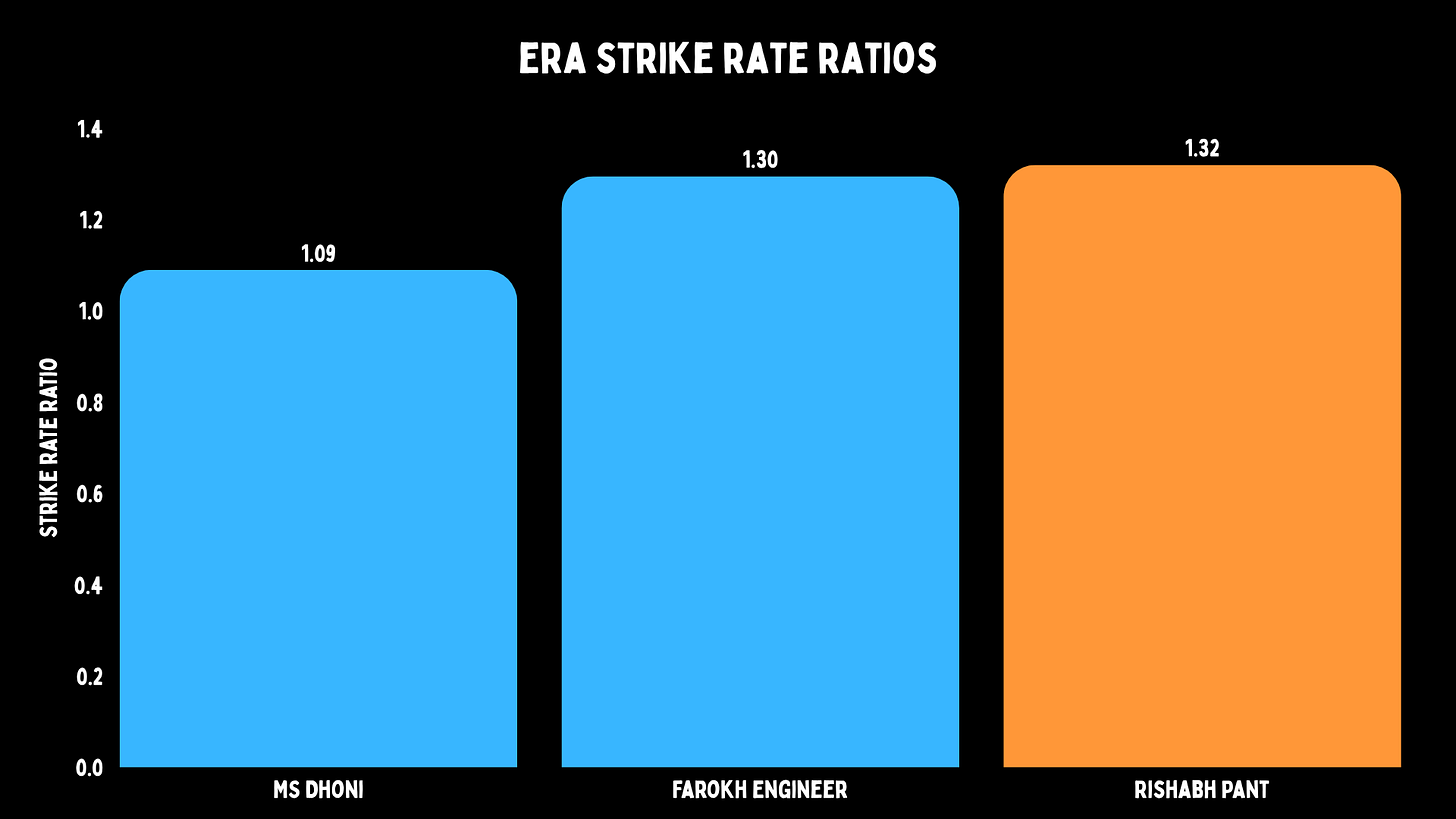

But then you get days like today, where Pant becomes only one of two Indian keepers to make a 100 and 50 in a Test, joining Farokh Engineer. For his time, Farokh was pretty attacking even if his strike rate was only 57 - the keepers in his era were way slower. So he was 30% quicker than them, whereas Pant is 32% quicker than the new guys.

Gavaskar grew up watching Engineer and then played with him in 13 Tests. He wasn’t even the only attacking keeper India had - Budhi Kunderan was around when Gavaskar was a teenager. Both men liked to whack it. For Gavaskar, that would have been an acceptable risk-taking. But those were innings from his own universe - ones tethered to familiar rules. Pant’s shot selection seems untethered, warped by different gravitational laws. But at the time, there would have been Engineer shots and innings that frustrated older players.

Because that has happened at every time an attacking player exists.

But Rishabh is a much better player than Engineer with the bat. And he now has as many hundreds in England as any keeper ever. Les Ames might still have him covered, but Alec Stewart and Matt Prior were both incredible players, yet Pant has been better so far in his career.

Now it is only him and Andy Flower with a hundred in each innings as a keeper. Pant hasn’t reached the Zimbabwean’s level yet. But that was awfully high; we rated him 38th in The Art of Batting. But in terms of impact, you could argue Pant has done things Flower simply could not.

Flower hit 20 career sixes. Pant is at 82, from 20 fewer matches. They play completely different roles. So Pant is producing incredibly attacking batting while taking up a top-five position. He’s like a weird hybrid of Adam Gilchrist and Flower. Without the average of either, but with parts of both.

It always felt like Gilchrist was trying to hit the ball hard, even when defending. Pant goes from flame-thrower to patting-puppies mode. His batting shows there is a decision being made - not that the vibes are taking him somewhere. And as for Flower, he just never had the ability to change the direction of a match fast. When batting at five, the median score when the Zimbabwean came to the crease was 63.5; for Pant it is 69.5. So both were in early, under the pump. But from that spot, Pant can get you out of it very quickly. Flower might do it more often, but it takes him an age. Pant detonates innings, often in both directions. He opens wormholes with every backswing. Sometimes it sucks in the opposition, sometimes himself.

When he sees an offspinner coming on, he doesn’t think, ‘Well, I should knock the ball around here’. He thinks, ‘this is a chance to get the big over’. For a long period, whether it be Shoaib Bashir or Joe Root, he was trying to go up and over cover almost every ball. He was dropped off one. It didn’t stop his attack.

Because he sees drops differently from other players. Because he sees everything differently from other players. He gives more half-chances than them, so he lives with that danger in a way Dean Elgar could never. He is taking so many risks that he isn’t living each one, they are part of his symphony of violence. He doesn’t hear each note, just the entire concert.

So he will continue to go hard and create even more chances and mistakes. Like when he fell over trying to scoop Carse and took an inside edge back towards his stumps. Or when he cut a ball off his toe that could have gone anywhere. He could pull back, but he doesn’t. He plays at his rhythm - one that he changes so frequently jazz musicians would get dizzy.

It means that opposition teams never feel comfortable. And through that, he can control the field. One of the reasons Brendon McCullum played the way he did was to take slips out of the game. Headingley is a ground where you get a lot of nicks. Rishabh Pant got regular edges, but England never had a full slip cordon. They were plugging holes on the boundary, having fielders out to slow him down. And when he made the mistake they were desperate for, there was no one there to take it.

Attacking batters make you feel like you’re in a different game, where there just aren’t enough fielders on the ground to stop them.

Think back to the 20th ball of this innings. India were in trouble, yet Pant has decided to whack Carse across the line, slog-sweeping a ball at nearly 90 miles per hour. But it takes the top edge and flies straight up. Pant thinks he is out. He doesn’t bother running.

For most batters in most universes, this is gone. But something happens to the ball in the air. A gust of wind seems to push it away from the leg-side fielders, over slip and the keeper who are tracking it, and nowhere near the fine leg fielder. It lands safely for another boundary in a fielding DMZ.

India were three down, not much more than 100 runs in front. It was a terrible shot at a terrible time. But it was safe. And so were the edges through slips and other half-chances.

Pant didn’t disappoint Sunil Gavaskar today. Instead, on a day he played wild slogs at terrible times, the keeper brought up his hundred, and the cameras found Sunil Gavaskar on the balcony, enjoying it as much as anyone.

What was the difference? Two bad shots at awful times. In one universe, the edge carries. In another, it drifts into space untethered to our primitive gravity. That’s the Pant Multiverse Theory: for every reckless shot, there's a timeline where it works.

Today there is a reality where Sunil Gavaskar is shouting Stupid. Stupid. STUPID. And another one where he admits the keeper is stupidly good. In Rishabh Pant’s multiverse, everything is possible.