Virender Sehwag - the first surgeon of slog

His IPL career was a phenomenon then, even more so when seen in context. He was playing death metal in a rock concert.

Everything is about context. If you hear a Cradle of Filth song in a dark and dingy club on the dodgy side of town, it seems right. If you are in a pharmacy buying some tissues and you hear:

“Maleficent in dusky rose

Gathered satin lapped Her breasts

Like blood upon the snow

A tourniquet of Topaz.”

It is going to stick out.

Context. When Virender Sehwag played in Test cricket it stuck out. No one had attacked that hard at the top before. It was loud, in your face, and it upset the quiet world of whites where we stopped for tea.

But when Viru was hitting out in T20, it wasn’t seen even as a real sport. It was slogging for the proletariat. Hitting and giggling for the great unwashed. Not proper cricket. So he didn’t make a lot of noise.

Now, we do take it seriously. And we understand it is a lot more than slogging. But even amid a rock concert environment, Sehwag was death metal at the start of T20 cricket.

“Toh mujhe chauke, chakke maarne me maza aata tha. Aur ek cheez yeh bhi hai na, ki ground me toh fielder khade hote hain, hawa me koi fielder khade nahi hote.” That was Sehwag in the Netflix documentary The Greatest Rivalry: India vs Pakistan. (“I loved hitting fours and sixes. And there’s also the fact that there are fielders on the ground. There are no fielder in the air.”)

If you look at 2008 to 2012, and compare Sehwag’s ODI numbers with openers in the IPL in that period, he was quicker than nine batters, including Sachin Tendulkar and Michael Hussey. Even Brendon McCullum and Shikhar Dhawan scored only marginally quicker in the IPL than Sehwag did. In ODIs.

Sehwag is one of cricket’s quickest-scoring batters ever. His first-ball fours in the 2011 World Cup made young boys fall in love with the sport. He is largely considered a Test great, but his white-ball heroics are slept on when we’re talking about all-time players. Discussing his ODI career is for another day, but here’s a guy who produced ridiculous numbers in the IPL, yet he isn’t really mentioned among the greatest Indian batters in the history of the league.

Virender Sehwag was playing 2025 IPL cricket in 2008. He was the first surgeon of slog.

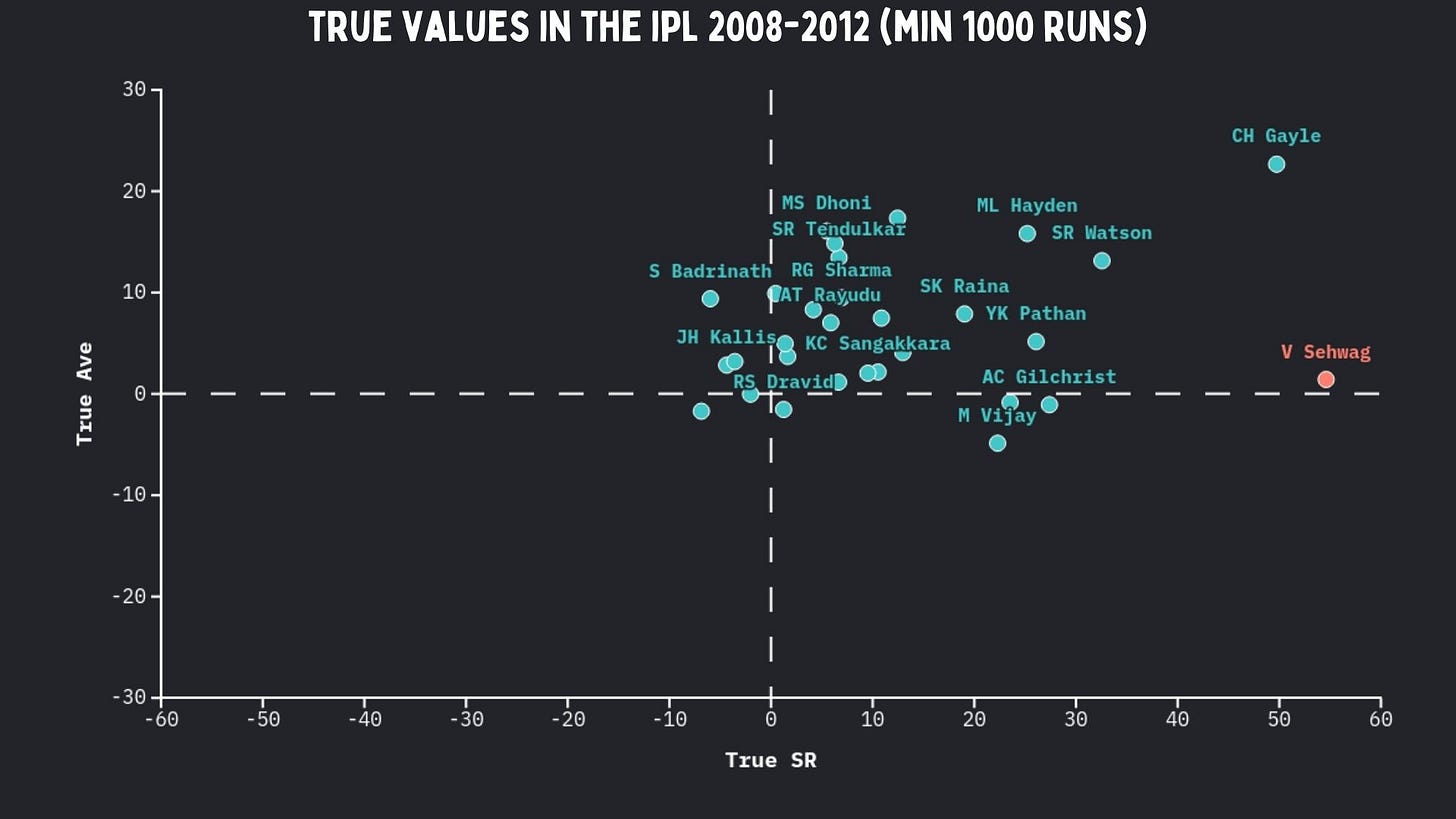

You want an outlier? Here he is.

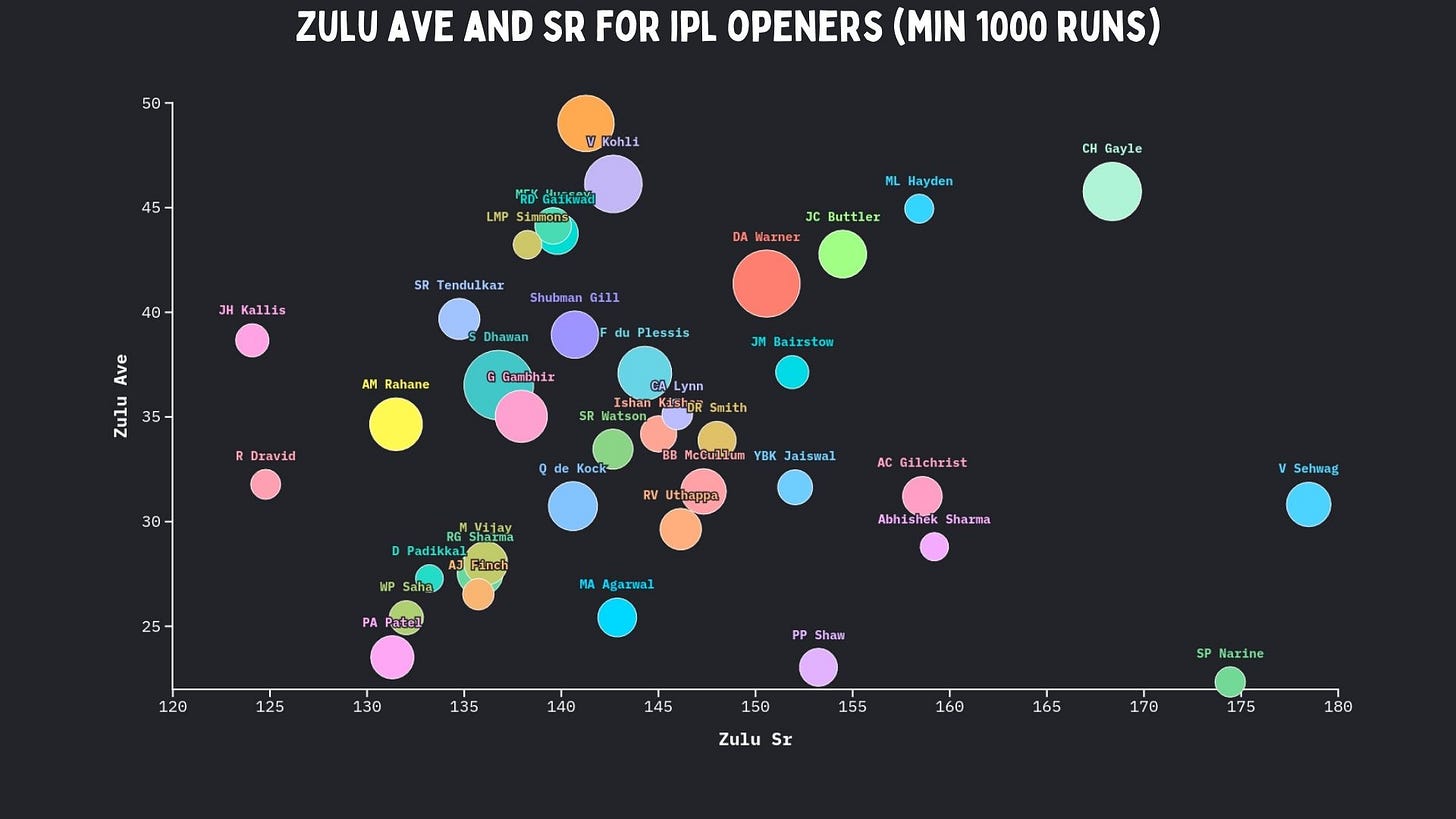

Sehwag comfortably sits on top of the tree in terms of true strike rate. Chris Gayle was one of the fastest-scoring batters, and Sehwag is nearly 14 points ahead of him on this metric.

Sehwag’s negative true average is comparable with Glenn Maxwell and Adam Gilchrist – two batters who also have high true strike rates, just nothing like Sehwag.

In 2008, his strike rate was 184.54 – his quickest-scoring year in the competition. Let us pause and breathe on that. It would still be incredible now, and the sport has had three tummy tucks, four boob jobs and an arse transplant since then.

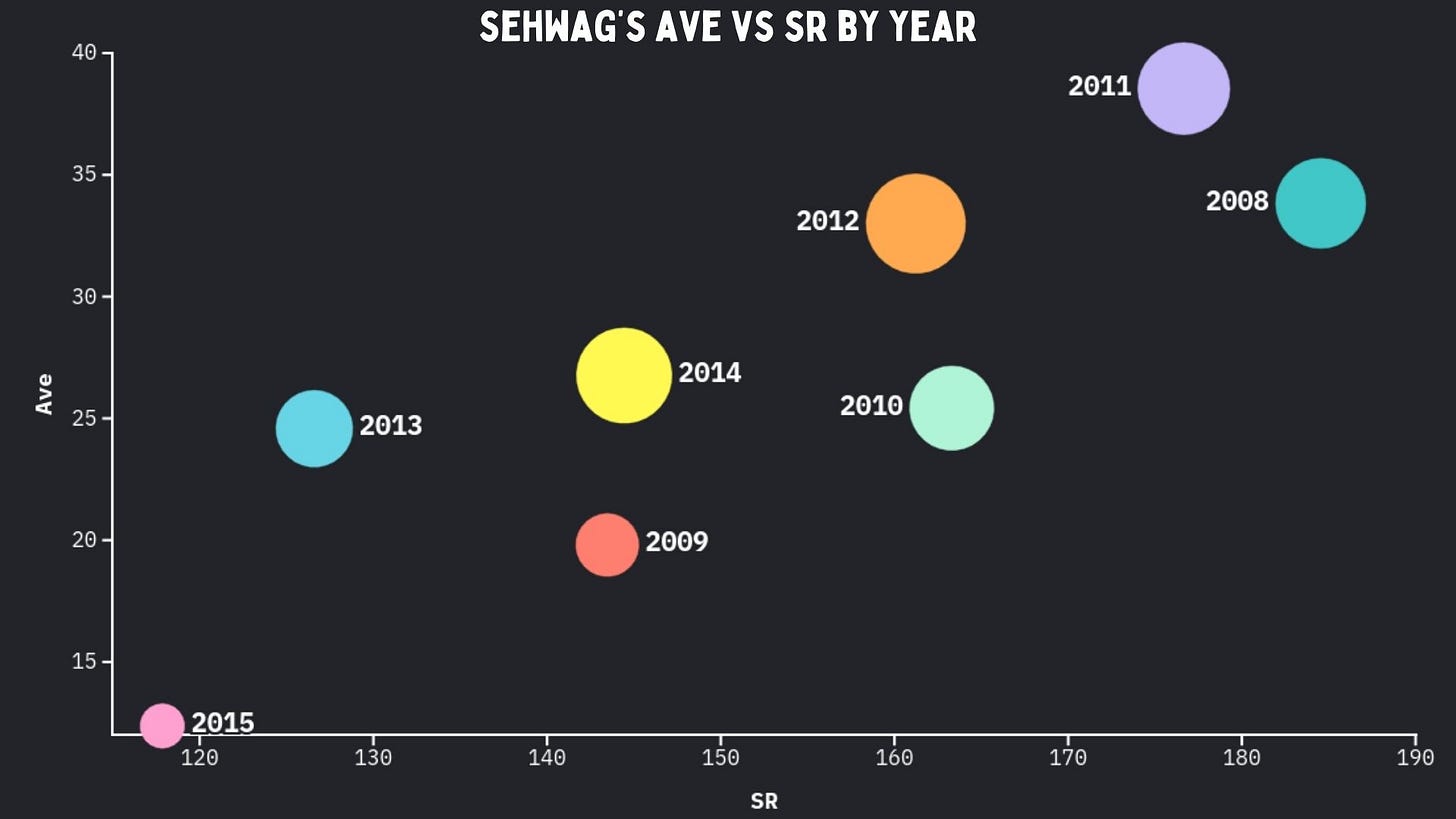

The most he averaged in a year was in 2011, with nearly 39 at a strike rate of 177. For context, Phil Salt averaged just under 40 at a strike rate of 182 in the last IPL, with an impact sub, and was considered one of the top batters in the league. Sehwag did this when T20 batting was 2D. He struck at over 160 in two more seasons, and averaged over 30 in one of them. In his last season in 2015, he made only 99 runs in eight innings at a strike rate of 118.

On true values, 2011 was clearly his standout year. He had a true average of 17 and a true strike rate of 65. He struck at 50 more than expected in four seasons.

Think about that, he was a half-run quicker per ball than expected four times. The man was clocking cricket.

Only two batters have had a higher true strike rate in a season – Gayle in 2011 and Maxwell in 2014. Gayle was an outlier on average as well, but Sehwag’s true average was better than Maxwell’s by about 9 points. His 2008 season also makes the cut for the top five true SR seasons. To put things into perspective, he is in the top seven three times, while no other batter is in the top ten list even twice.

They should be building statues of him.

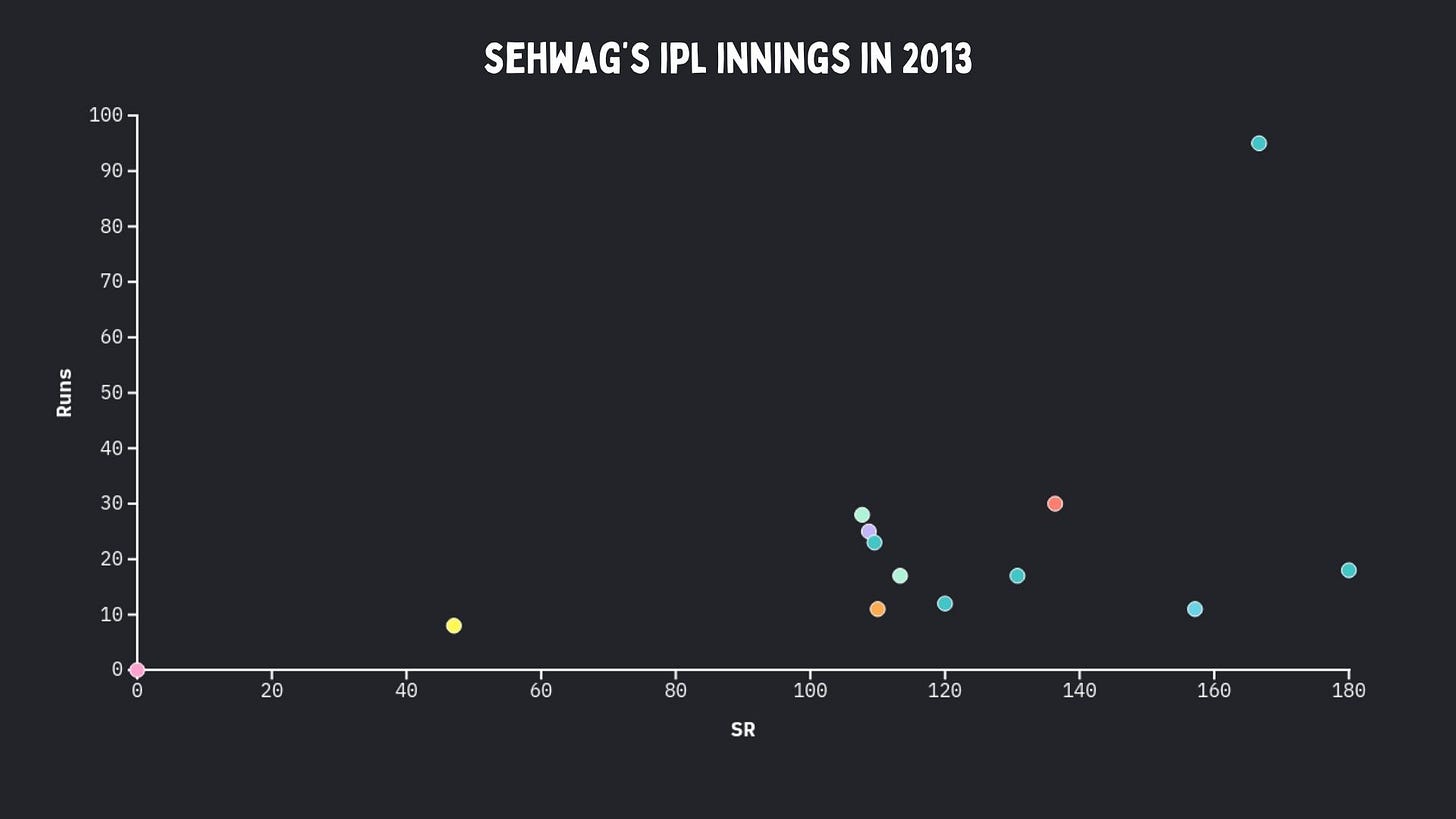

Although his raw numbers in 2013 don’t look great, his true strike rate was still 23. He played one great knock of 95 versus the eventual champions, Mumbai Indians.

But even accounting for the era, there were a few uncharacteristically slow 20s. So that one big innings played a significant part in his high true strike rate, plus the fact that batters just weren’t utilising the powerplay the way they do now. Sehwag struck at 121, and that had the ninth-best strike rate among the 32 batters who faced at least 50 balls in the first six overs.

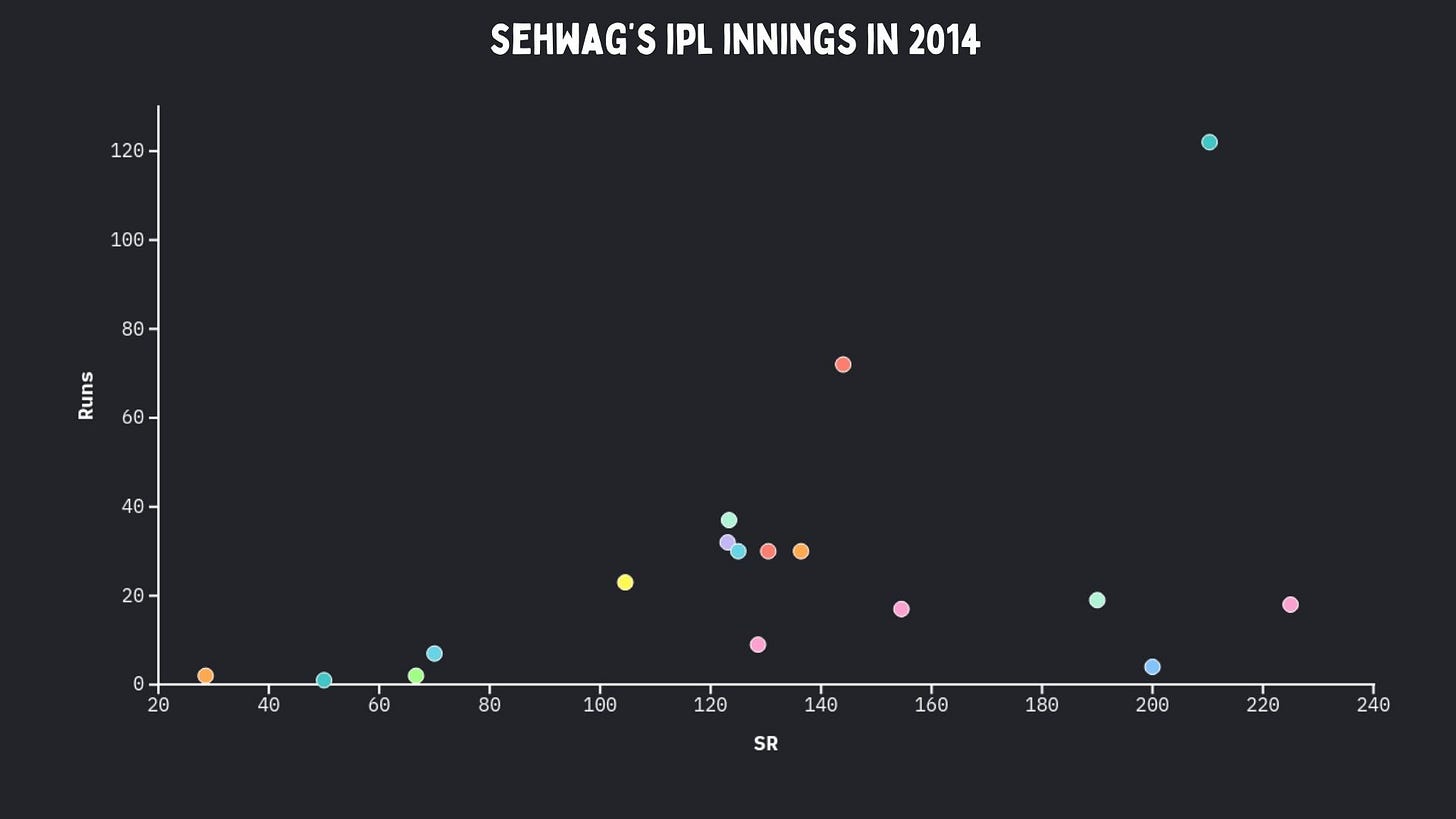

His last two seasons were for Punjab Kings (they were called Kings XI Punjab then). Obviously, 2015 was his worst IPL season. But just a year before that, he managed a true strike rate of 34. This was the season Punjab made the final. Fans fondly remember the team for Glenn Maxwell and David Miller, but Sehwag had a pretty decent season himself.

He smashed a huge 122 off just 58 balls against CSK in Qualifier 2, a game which is also remembered for Suresh Raina’s epic 87 off 25. He also made 72 off 50 against an elite KKR bowling attack, while the next-best score was 15. Weirdly, he again had a few relatively slow 30s by his standards, so those two big knocks do carry his numbers a bit. But his strike rate of 136 in the powerplay was the fourth-best.

So even in the final three years of his career, he was alright when the field was up.

We can split his IPL career in two parts – 2008-2012 and 2013-15. For that initial five-year period, he was comfortably striking at above 50 more than expected for the balls he faced, with a positive true average. In the last three years, the true average dropped to below -5, but his true strike rate was still an incredible 27. Remember, he had played his last international game before the start of IPL 2013.

His true strike rate is the highest of any player ever in the IPL in a five-year stretch. He is more than five points clear of Sunil Narine in second place.

From 2008 to 2012, only Gayle’s true strike rate was somewhat close to Sehwag’s, albeit with a better true average than anyone else on the graph. But Sehwag’s true average was close to that of Gilchrist and Warner, yet his true strike rate was miles better. In fact, a lot of anchor-type batters of his era like Jacques Kallis, Sourav Ganguly and Rahul Dravid had a similar true average. He was doing it while scoring at rates no one had dreamed of.

The numbers are incredible, but what about the effect? Impact is how we calculate by how many runs a batter changes the predicted final score. Both your strike rate and your average matter in terms of how much impact you create.

For example, the par score in the IPL since 2022 is about 175. If you’re an opener and the predicted score goes up to 185 by the time you're out; your impact is +10. That is a big jump from one player.

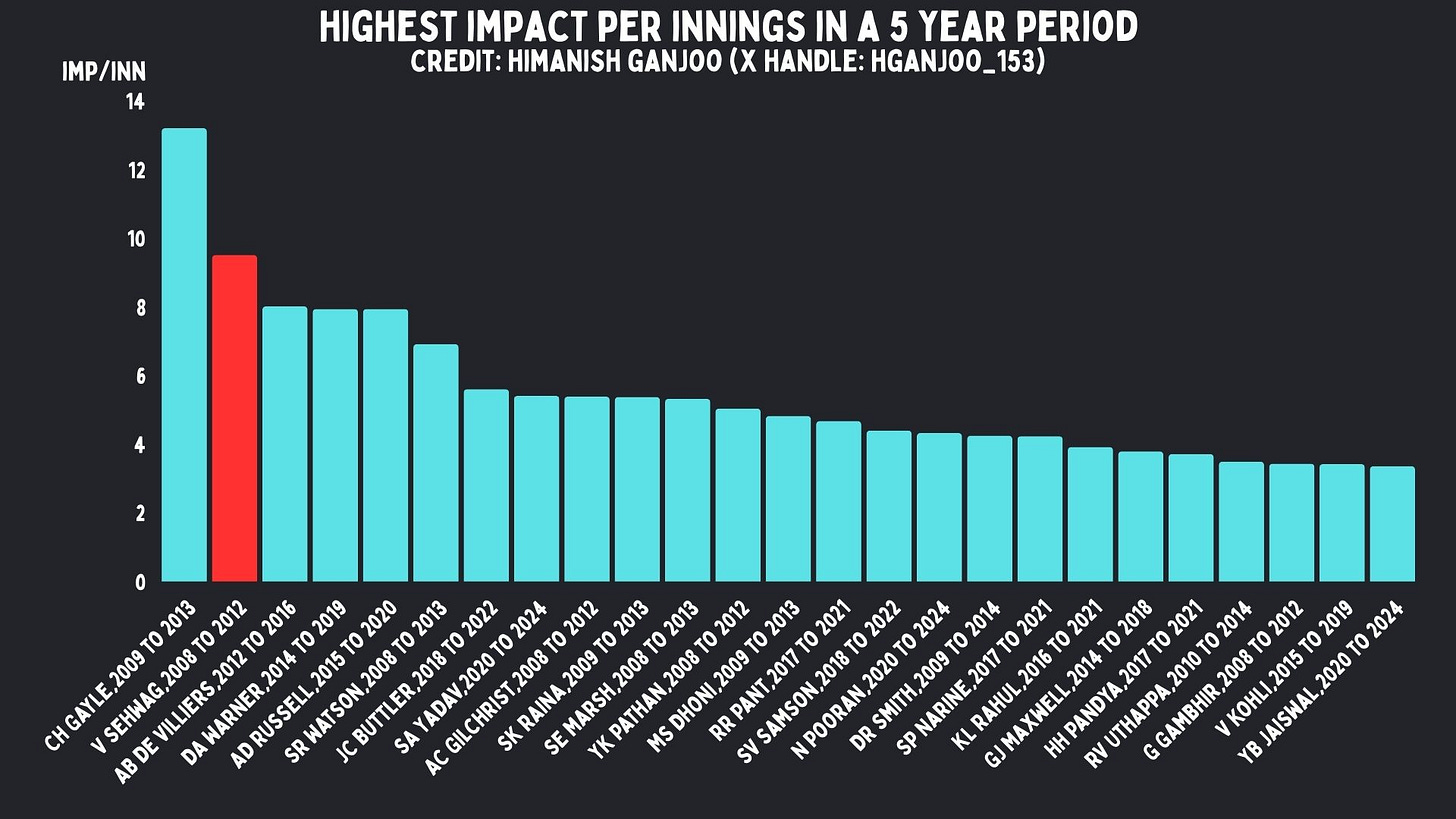

We've looked at the impact per innings in a five-year period. Peak Chris Gayle was unmatched, as he changed the predicted final score by 13.22 runs by himself from 2009 to 2013. Sehwag is second – ahead of AB de Villiers, Warner, and Andre Russell. These are batters who are considered to be in the S tier of IPL batting. Yet, Sehwag isn’t often mentioned in the same breath. Like his innings, he was here for only the briefest of moments. But in terms of peaks, Sehwag’s right up there with the best.

Yes, we made it a minimum of nine innings per season to include the Rooster, Jake Fraser-McGurk. We mentioned how Sehwag had three seasons that made the top ten in terms of true strike rate – 2011, 2008 and 2012. His 2011 season is seventh, while 2008 and 2012 are 12th and 26th on this graph.

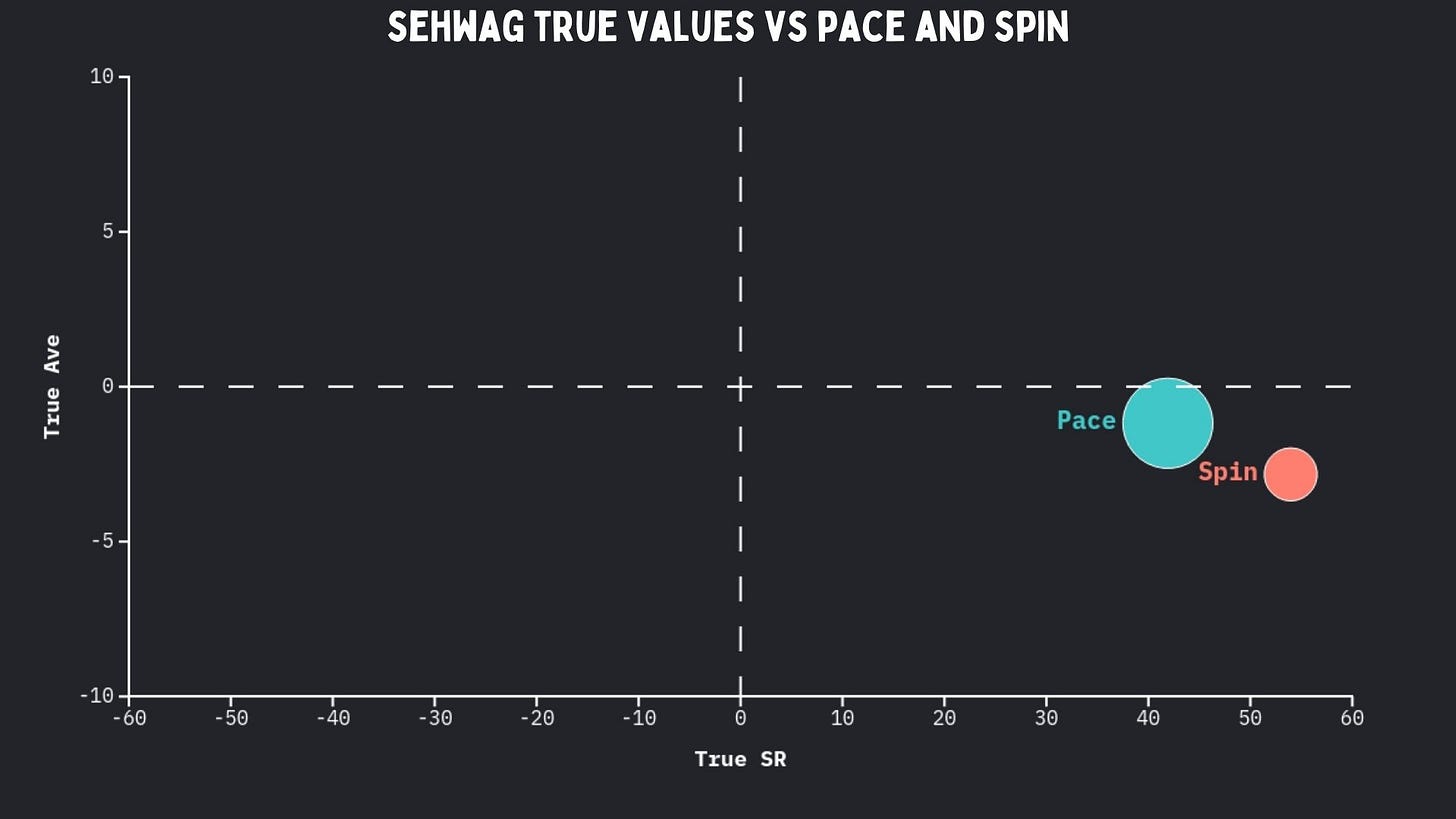

Sehwag had a true strike rate north of 50 against spinners, but he still struck at 42 against the quicks. It really didn’t matter to him what pace the ball was coming, just what pace it left his bat.

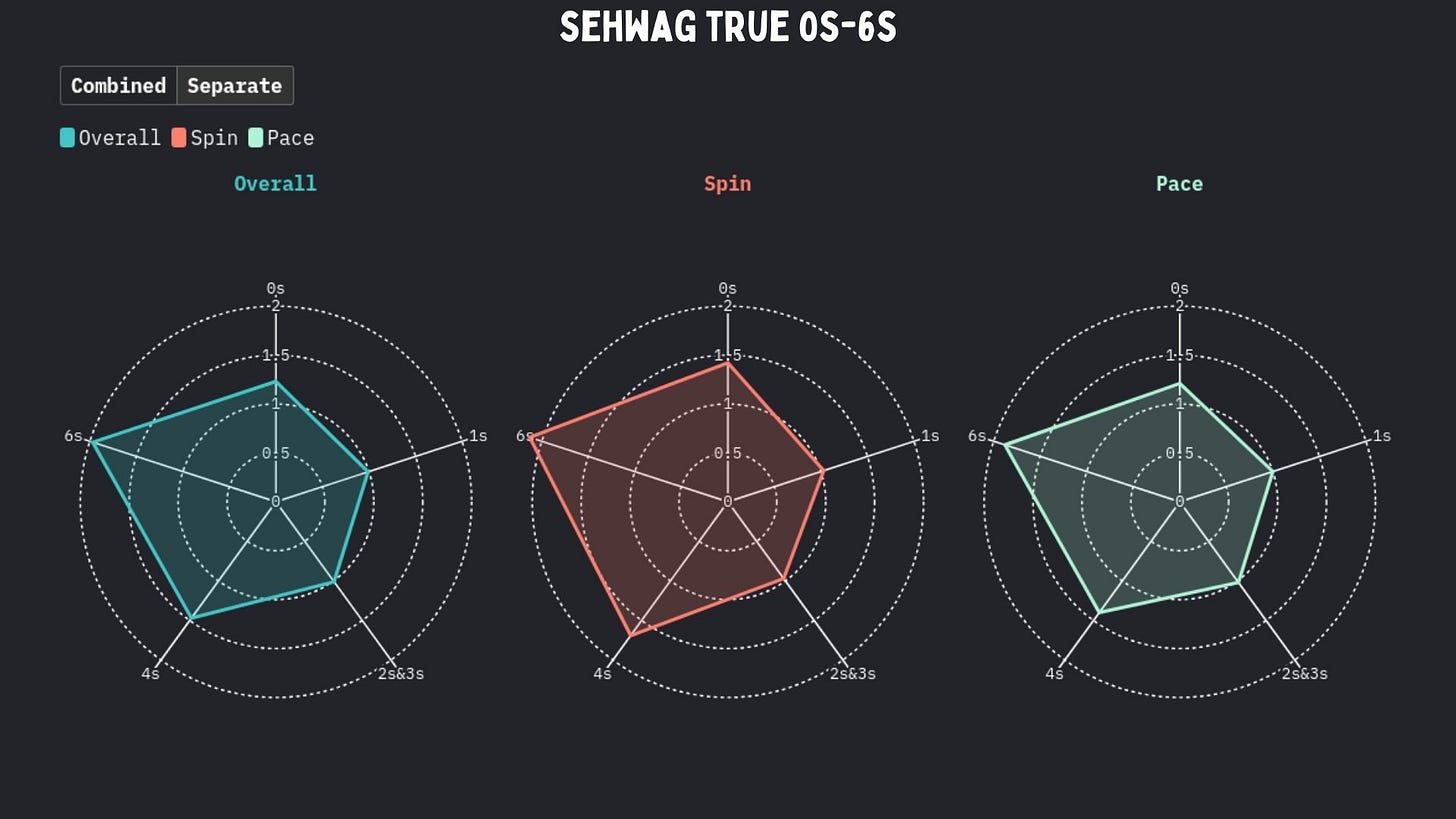

Against spin, he hit 69% more fours and 113% more sixes than expected. Despite the ‘see ball hit ball’ credo, he didn’t chew up dots and actually scored singles at a par rate. He did take fewer twos and threes than an average batter, but why bother running when you can hit like him?

Against the quicks, he was above par on every metric except singles, where he was exactly par, and a bit better than that at taking twos and threes. Again, he wasn’t fond of dots. He scored 40% more fours and 88% more sixes. So to sum up, he smashed pace and spin, and didn’t have too many dot balls.

For most batters you’d say either of these numbers would make him a specialist against quicks or spin.

When we compare his first innings versus his second, Sehwag had a better true strike rate and average when he knew the target. His true strike rate was 13 more in the second innings than in the first. In ODI cricket though, it was the opposite, and he was better while setting a target.

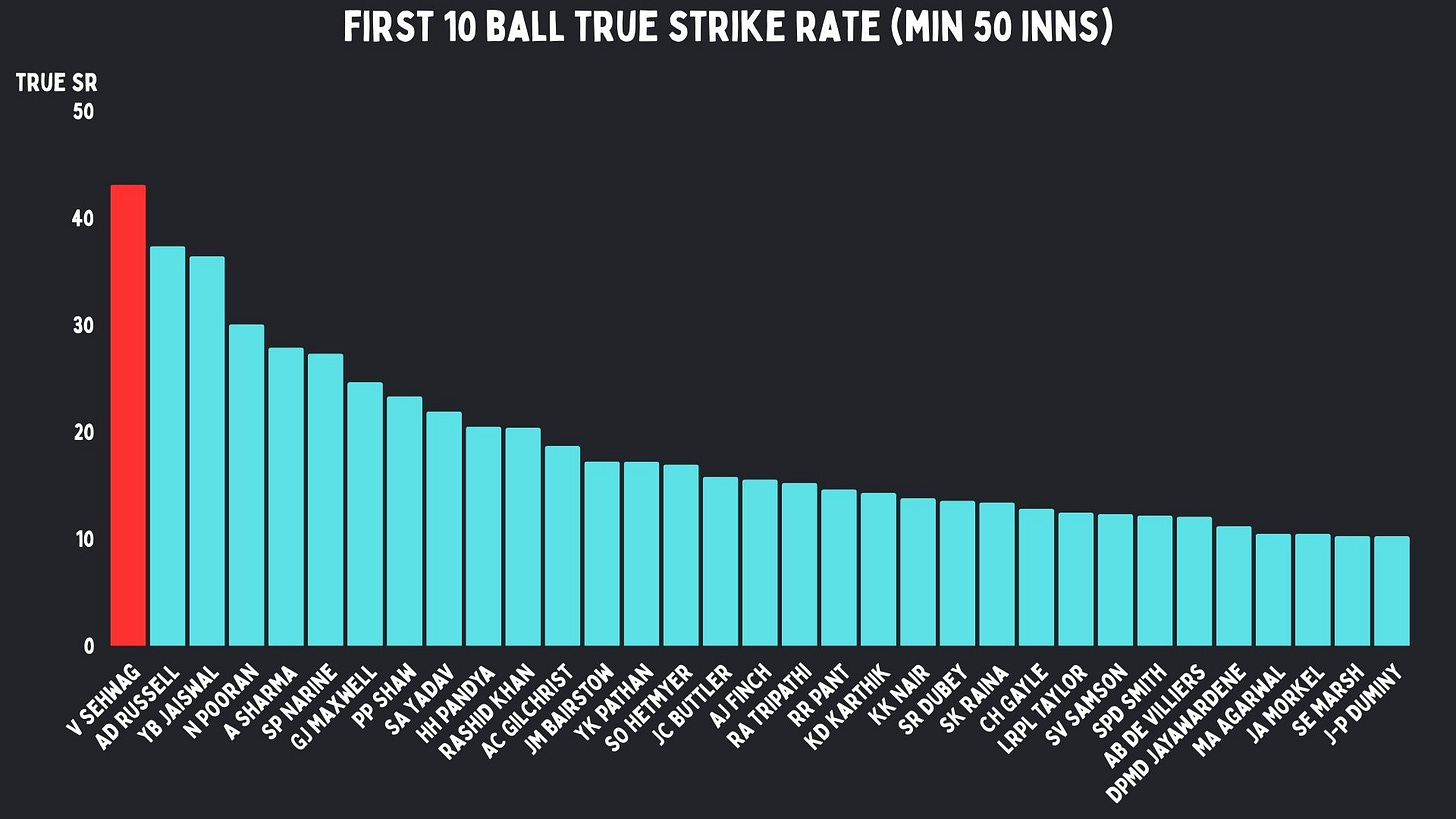

Sehwag also has the best first ten ball true strike rate in IPL history. This includes innings where a batter has faced less than ten balls, so that we account for finishers who may not always face the full set. Russell, Yashasvi Jaiswal, Nicholas Pooran and Abhishek Sharma round out the top five.

Sehwag preferred spin to pace, was alright as a strike rotator despite being an elite boundary-hitter, hit over the rope, had better true numbers in run chases, and was one of the quickest starters ever in the league. And at no point do we see a major weakness in his game when it comes to scoring rate. Yes, his true average was close to par or less than it most of the time, but he batted at breakneck speeds. None of this truly makes sense.

We’ve used the Zulu metrics for average and strike rate, with IPLs 2022-24 as the timeframe for the modern era. So with the assumption of linearity, if Sehwag’s entire career was played in what we have defined as the modern era, he would average 31 with a strike rate above 178. Handy.

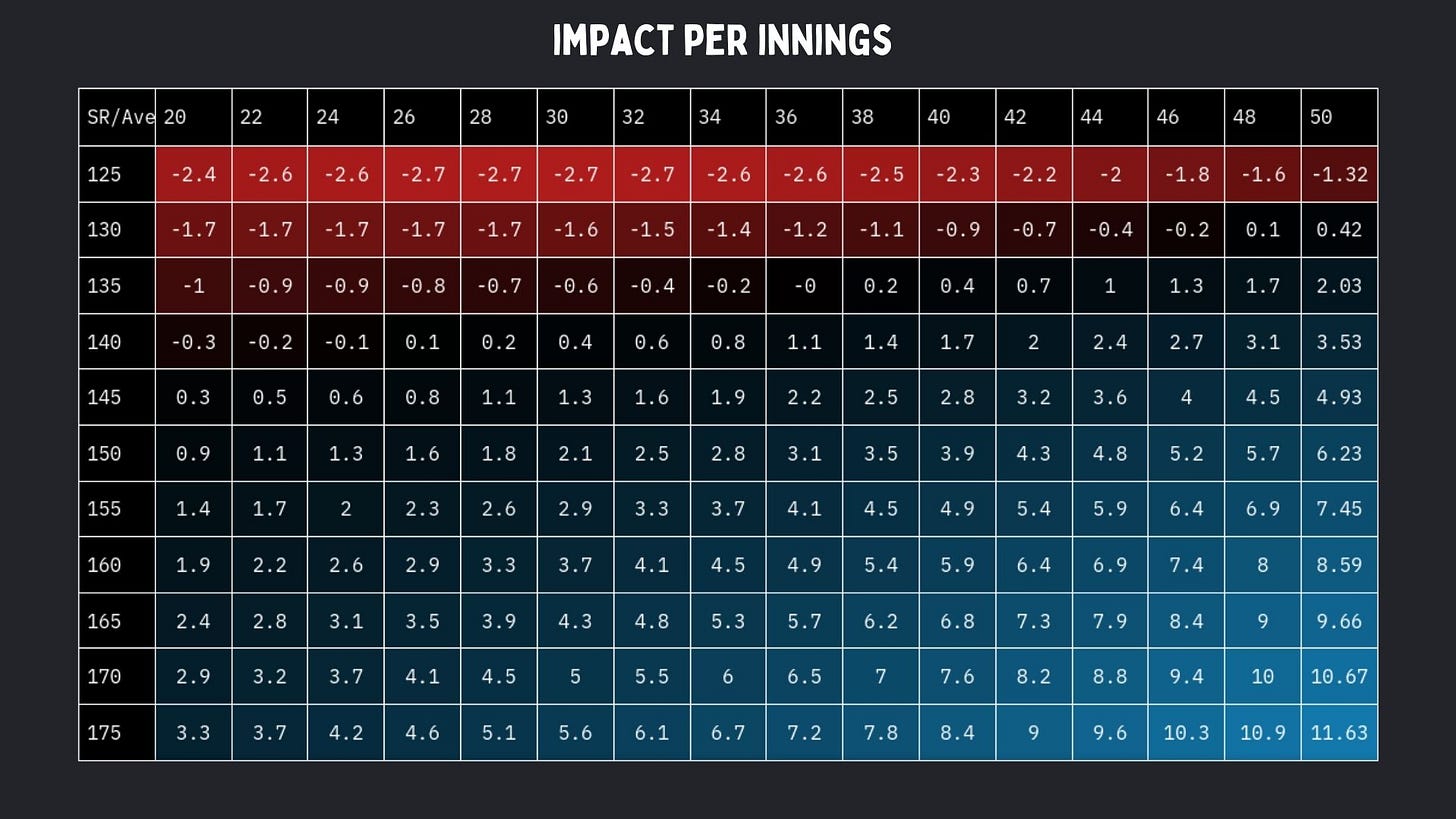

This sexy beast below is the impact table. We’ve looked at how openers deviate from the mean by eras, and then normalised it to the modern IPL cycle. We have done this because the impact is designed explicitly for 2022 onwards, and we needed everyone on the same scale.

This shows us just how important average and strike rate can be. A player who averages 24 while striking 130 on the Zulu metrics would have an impact score of -9.3 runs for every 100 deliveries, while someone going at 32/160 would increase the par score by 20.3 runs per 100 balls.

We did this so that there’s an easy ‘one number’ solution to compare players instead of analysing thousands of lines of data every time. We don’t love one-number solutions, but as far as those go, this isn’t too bad.

Saying that a batter has a great impact over 100 balls might be a bit like saying Tim Southee would have scored more runs than Sachin Tendulkar if he faced the same number of balls. It’s unlikely if he gets out more frequently.

We look at a similar thing here. A batter averaging 30 at a strike rate of 175 would get out more frequently than someone averaging 50 at a strike rate of 140. What we want to know is whether the trade-off on runs is worth the boost in striking. An average innings is essentially the average divided by the strike rate times a 100. So if you average 30 at a strike rate of 175, your average innings is 30 off 17 deliveries, whereas 50 at a strike rate of 140 would be 50 off 36.

According to the table the 30 off 17 creates more impact than the 50 off 36. So in this case, the tradeoff in average is worth the boost in strike rate.

A 50 off 40 is better for your team than a 25 of 20, even if both have a strike rate of 125. This is mainly because someone who makes 25 off 20 and then gets out isn’t doing anything for the team. You’re not impacting the score in terms of strike rate and once you get out, you leave your team in a worse position.

This is just to show you how much average and strike matter for the same impact. For the first 16 overs of a match, the strike rate is twice as important as average. At the death, the average is basically not a factor.

The overall equation is based on the whole innings. So for batters that mainly bat in the first 16 overs, strike rate is roughly twice as important for the same impact. The table mainly applies for top and middle order batters, since they face most of the overs. So it might not be particularly useful for death overs batters.

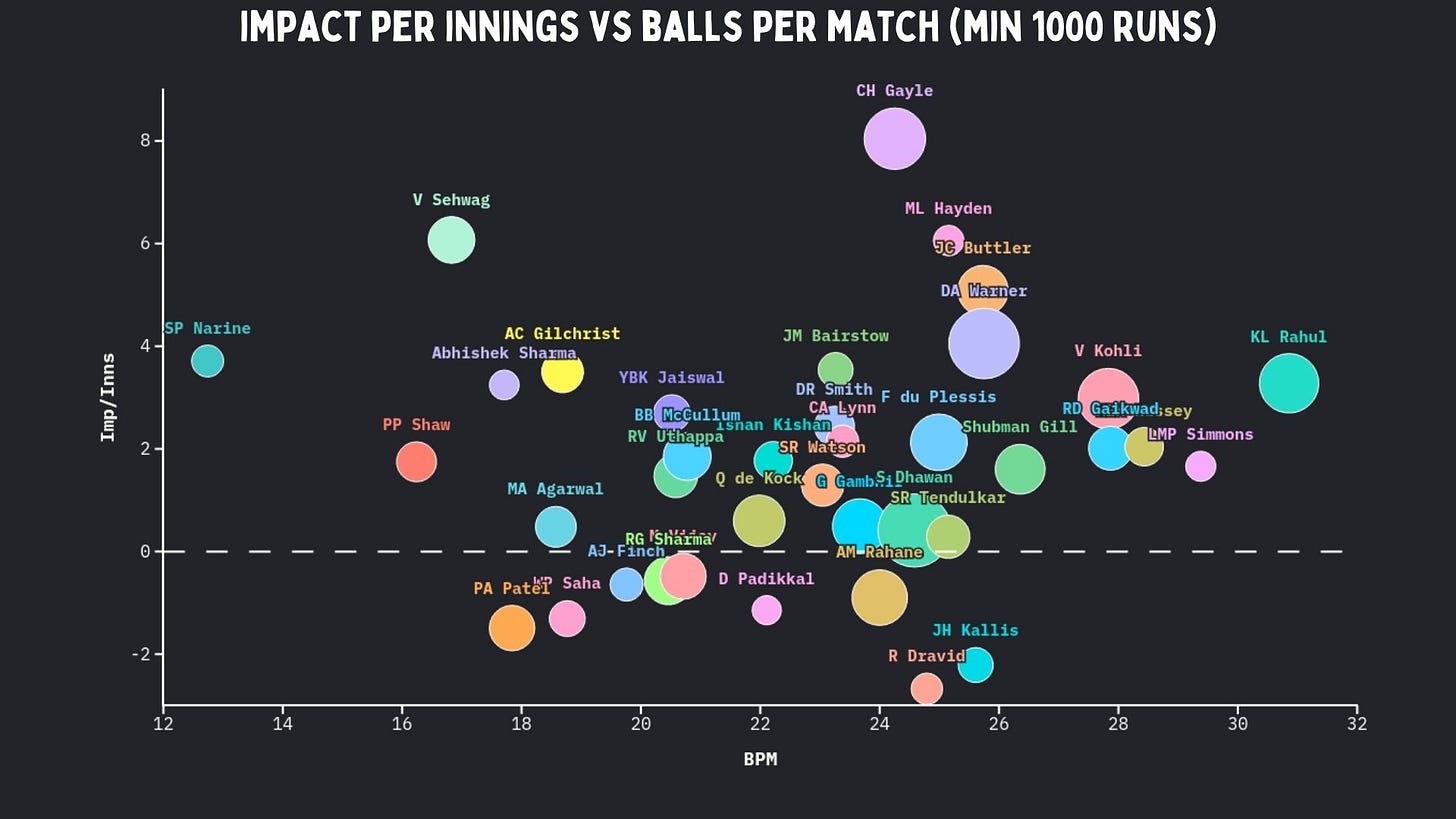

When looking at how many balls per innings openers face, only Narine and Prithvi Shaw face fewer than Sehwag. One is a bowler who makes runs against all odds and statistics, and the other was a promising batter who’s had a decline. Not great company on paper, but bear with us. Abhishek and Parthiv Patel are the other two batters who, on average, play less than three overs per knock. On the extreme right, we see anchors like KL Rahul, Ruturaj Gaikwad and Virat Kohli, who face about 27 to 30 balls per game.

Sehwag’s Zulu average and strike rate was 31 and 178. So according to this table, his impact per innings would approximately be 6. For comparison, Kohli and KL’s impact as openers would roughly be close to 3.

The graph above shows it best. Sehwag faces nearly 11 to 14 deliveries per match fewer than Kohli and Rahul when they open the batting, yet has nearly twice the ‘impact’ in each innings. Matthew Hayden basically has the same impact as Sehwag, and only Gayle is ahead.

Sehwag has the highest impact per 100 balls of all openers. To explain it in simpler terms, Sehwag changed the final predicted score by 0.36 runs for every ball he faced on average.

We can see how most of Sehwag’s innings in the first five years of his IPL career had a positive impact. There are several innings with an impact of over 20.

He played 18 such knocks, which is the fourth-most of all batters in the history of the IPL. But his career was also shorter than some of the names on this graph.

So we’ve also looked at the percentage of such knocks played by each batter. Sehwag is now second behind Gayle, and is one of the four batters who have had an impact of 20 or more over 15% of the time.

Sehwag’s lowest strike rate in an innings where he crossed 50 was 144, in that innings of 72 at Cuttack that we talked about earlier. Every other time he scored 50 or more, his strike rate was north of 160.

His best innings was probably when he made 119 versus Deccan Chargers, chasing down 176 with the next-best score being James Hopes’ 10-ball 17. He smashed fours on both sides of the ground, and hit sixes either on the onside or in the V.

He crossed 30 in his IPL career 35 times, and struck at less than 130 just six times despite playing in an era where it was a lot more common. One of those was a sub-100 SR knock of 32 in a chase of 93, and four others came in the last two years of his career. The man barely played net negative knocks, especially when he was at the peak of his powers.

***

So, where does Virender Sehwag rank among the greatest Indian batters in the IPL for us? I’d still say Suresh Raina had a better career overall when we factor in the longevity. But no Indian batter ever scored as fast as Sehwag did over a consistent stretch of years. He’s clearly the best Indian opener, and probably has a case for being third behind Gayle and Warner when we include overseas players as well.

Plus, he dominated the tournament at a time when T20 cricket and the IPL were still in a nascent stage. Teams were still opening with slow-scoring batters like Rahul Dravid, Jacques Kallis, Graeme Smith and Sourav Ganguly. Did that make it easier for him to stand out? Possibly, but the fact that his raw numbers stand out even now means he was doing something special.

In the context of the modern game, if prime Sehwag came out to open for SRH tomorrow, he wouldn’t be out of place.

At the time people saw what Sehwag did as noise. He was ‘reckless’, not putting a suitable value on his wicket. People saw it as frivolous. Now we can dissect it in a modern context. Taking a second look, the loud man who slapped the ball around was something far more special.

The Tenor of Tonk, the Honourable Hoickmaster general, the Professor of Pongo. The man who made an impact before the sub. The loudest guy in any room, then and now.

Gen Z in India only knows Sehwag from his media role and do not understand his no nonsense take on the game.. They even denigrate his Test record by talking about his average in SENA. Oh the naivety of the young !