Why does everyone chase at Headingley?

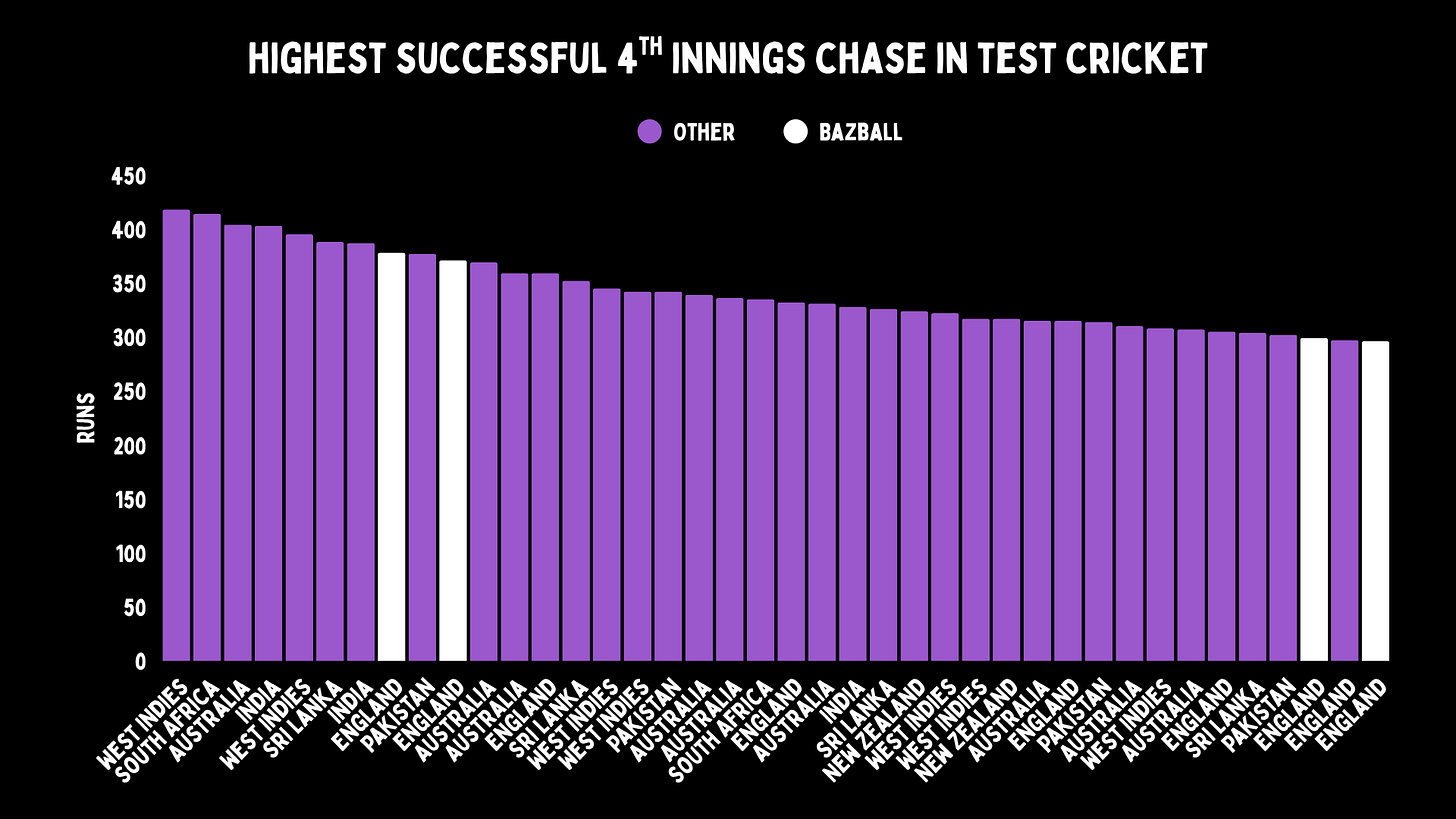

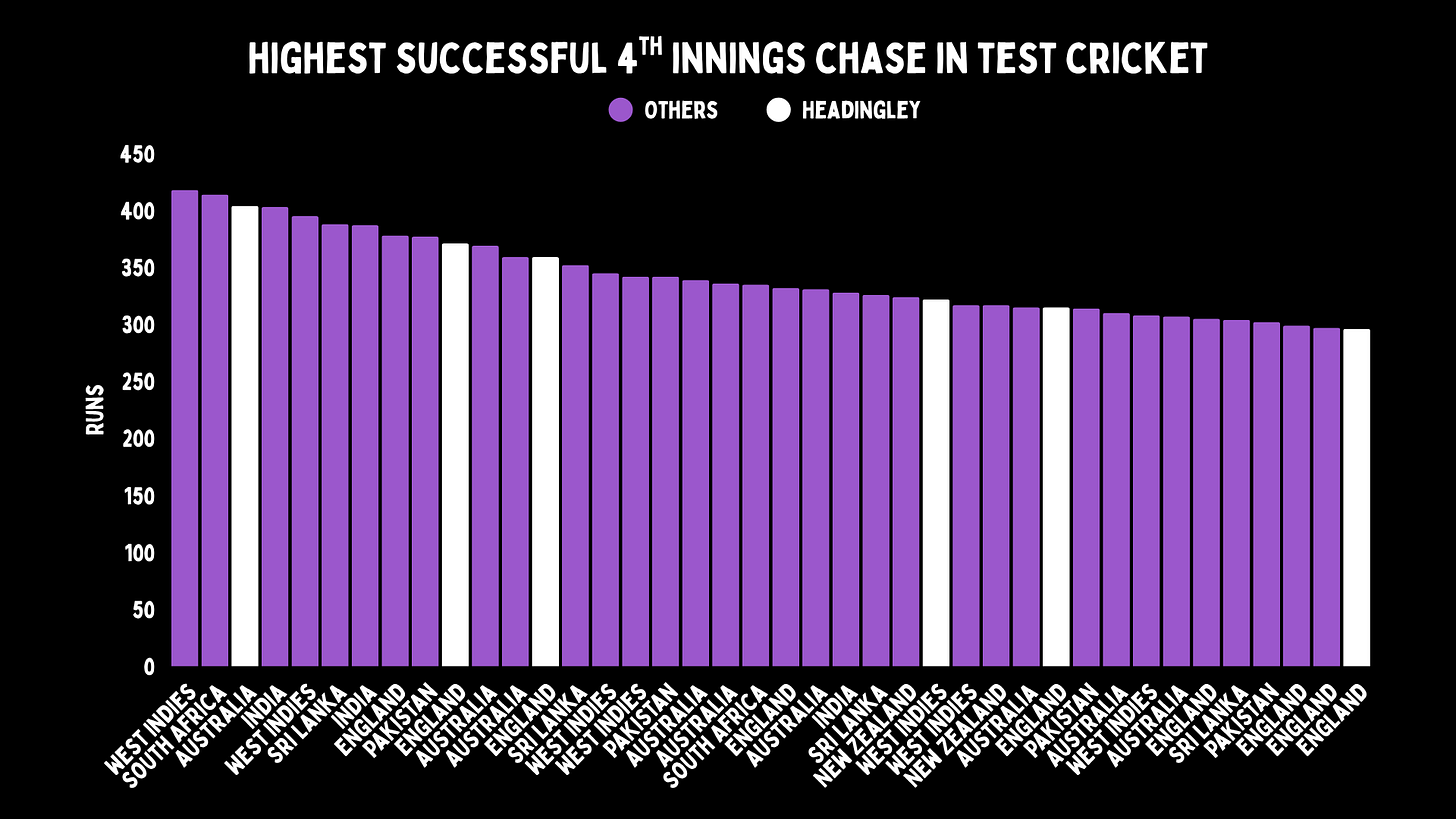

Of the 40 largest chases in the history of our game, Headingley has 15% of them.

UK readers can get their copy of the book here:

A chase is supposed to be hard in cricket. Dust from the footmarks. Cracks opening up. The wicket is literally dying with a lack of water. The batters are supposed to be as well. And even in a world where chasing in white ball cricket is what everyone does, doing it in Tests is still really tough.

Except in one place, where the wicket is reborn. Undead, is probably the best term - though not in the conventional cricket sense. Because this pitch is where the hunter and hunted seem to switch, but only for one innings. At Headingley - with nearly 400 runs to play with - the bowlers are prey to an army of batters who seem to chase endlessly.

The MCG had three of the 40 biggest chases in the history of cricket. Today it has two. That is because Headingley now has six. Only Kingsmead in Durban also has more than two, and then only three. So of the 40 largest chases in the history of our game, Headingley has 15% of them. It is like this pitch is bitten, and dead, only to be resurrected as something else for the fourth innings.

What do you even do with a stat like 15%?

You would assume that Headingley must be one of the best pitches to bat on in the fourth innings in the history of our game. That is a fair and reasonable thought process, but it is also wrong. Yes, four of these chases have come in modern times, but while that has happened, batting in County cricket on the same wicket has been tough.

Fourth innings chases in domestic cricket are usually easier, as they come earlier in the match, and are often assisted by declarations for points. But just making runs in the fourth innings of a county game has been tough at Headingley.

So, in a normal match here, you would expect the team trying to get a big total to do so at the typical rate. But in Tests, Headingley is a freakish outlier. A graveyard that only wakes at night.

Four of Headingley’s winning chases have come since 2006. In that time, we have stats on this ground for county versus Tests. The wickets fall at 25.4 when Yorkshire are playing, meaning this is a mega bowling pitch. Put a Test on, and that average goes up to 32.17, those are batting-friendly numbers.

In normal cricket, in the fourth innings, batters are the prey and bowlers are the zombies. At Headingley, their roles swap only for the last knock of the game. Why does everyone chase at Headingley?

There was a time during this chase when it looked possible that England would hunt down 371 without losing a wicket. Yes, of course India had created plenty of half chances, and Crawley’s innings was fortunate, but for a moment there, it was as if they couldn’t actually lose a wicket.

There is almost always a time in any large chase where it feels like the batting team could do it. But here, there were so many, that you stopped counting. Headingley had started flat, but by the end there was some up and down bounce, occasional sideways movement and some footmarks for Jadeja. But outside of the first spell, it always looked tough for India.

It doesn’t help bowling to England in a chase. A team whose fourth-best batter was extras has suddenly become the most aggressive and single-minded team in a chase that we’ve ever seen. They smell a victory and follow it en masse. In most cases, more like the 28 Days Later zombies than George Romero’s slow plodders. But today, while there were glimpses of Bazball, it was mostly just normal batting.

Either way, it does suggest that going up against England on a wicket made for chasing is not ideal. It should be the pitch that suits England the most when batting second. This is their second win here in the era of Bazballing. But even before England won the moral cricket World Cup, others chased here too.

A quick history lesson. Back in 1948, the world record was set here by an Australian team called the Invincibles.

They chased 404, the best before then was 332. However, it was an obscenely high scoring match, the lowest total was 365/8. And they had a guy called Bradman in the side, and he made 173 not out. So, we can put an asterisk on that.

The next one is a little more interesting, as England were set 315 in a dead rubber Test in which the bowling attack was Shane Warne, Brett Lee, Jason Gillespie and Glenn McGrath.

Against that, only one player made more than 55, it was Mark Butcher and his 173 not out. He made 55% of the chase, and if you take out extras, 61%.

Then we have the weirdest one, where England were rolled for 258 in the first innings, but then scored more than 400 in the second innings to set the West Indies 332 in 2017.

The West Indies fell to 53/2 when Kraigg Brathwaite and Shai Hope came together. But they batted for a long time in the first innings, both making tons. In this one, Brathwaite fell five short of another, but Hope was not out on 118. They made almost two-thirds of their team’s entire match total, and Shai Hope NEVER MADE A HUNDRED AGAIN.

In 2019, we all remember the end. But what about the start? Australia made 179, three players made it into double figures, England didn’t cross 70 in reply. Then Australia put up 246 to set England 359.

In reply, England were 286/9 - which was already the most runs in an innings for the game - needing almost 100 more when Jack Leach came in to face 17 balls with Ben Stokes. The English allrounder had been playing and missing Lyon for hours, was suddenly clawing out of his grave and then went about eating the hearts of the Australians in one of the best innings - and endings - ever.

Then we have our first Bazball chase. The third Test of the series, so by this point we already knew England were good at this batting second malarkey. In the first, they had done a pretty normal chase at Lord’s, but then it went crazy batshit insane at Trent Bridge.

Headingley was a game where 300 was about par in every innings, meaning that England had a decent chance. But in Bazball’s maiden summer, once the balls got soft, it meant the Kiwis had little chance. Still, Jonny Bairstow didn’t have to do them so dirty.

So what have we learned from that? It does take an extraordinary innings most of the time. Duckett’s knock today is not quite the Bradman, Butcher and Stokes level, but that’s because the bar is so high. This is still an incredible innings, even by Headingley standards.

But they are also seemingly happening a lot more frequently now. In 2016, Headingley only had two. It has six now. And when you break it down by innings, it does suggest that the fourth innings is the best time to bat, and not by a little. The wicket is well and truly resurrected for batting.

If you look at all innings, this has not been a batting wicket for the last 25 years. Usually the ball swings or seams and the slips have a field day. Headingley is known for helping the quicks.

But in the fourth innings that all stops, and this spicy wicket regenerates into a road. There is another pitch that used to do this at times, it was the WACA. Both surfaces can crack and give you uneven bounce. But when the ball missed the cracks, it was a great wicket to bat on. And perhaps in both places, as the game goes on, the slips are no longer the batters biggest threat.

On a normal wicket, spin would come in. But Headingley and the WACA don’t have that. So you end up with a wicket which can get very flat. The WACA had more bounce variation, because it started so high, plus the cracks could get huge. Headingley is much more tame, and then loses its sideways movement, and often doesn’t replace it with any huge threat.

But this is all new. Yes, the Butcher and Bradman chases are old, but they are the weird ones. From 2015 onwards, it is clear this wicket has completely changed. By the end of the match, it is just tough to get wickets.

Even in Sri Lanka’s famous win here, England batted for 116 overs, and the last partnership took up 20 of them. When it gets late, the wickets run and hide.

But we don’t get many fourth innings in Tests, so let’s check back in with Yorkshire.

This chart is all over the place. But you can see that a few years back, there were a bunch of high scoring years in the fourth innings. Then it got low for a long time, before just recently picking up again.

But let’s look at some years by random, 2017 was a reasonable year to chase, and that was when Shai did his thing. But in 2019, it was basically impossible to chase, yet Stokes and Leach won it from nowhere. In 2022, no one was scoring at the end, but England did. And this year has been the same.

None of this makes any sense at all. Now, county games are different; maybe Headingley produces an entirely different deck for Yorkshire than England. That is fine. But they are the same strips, on the same square, often at the same time of the year. It makes sense they are better for batting, that happens a lot in Tests. But it does not make sense that they are suddenly so good for batting only at the end. That is harder to swallow.

Why does it always happen here? It could be something to do with rage-infected monkeys, the weird modern surface that stops moving laterally, or there is just a sense of randomness that helps - like a Butcher knock, Shai’s last hundred or Australia forgetting how to take the bails off.

But what I do know is that here in Leeds - more times than I care to remember - when there's no more wickets on the pitch, the batters will walk the chase.

Headingley is not a batting ground, it’s a chasing ground.